the Empathy List #125: Codependent with my Church

Uncoupling from my dysfunctional, codependent relationship with the American Church

Hello friend, Liz here.

Before I took my summer publishing break, I had started a series about returning to church after your religion has hurt you and/or you have shape-shifted so that you no longer fit into the strictures of your old religion. (Okay, I’m describing how evangelicalism turned into my own “tight pants.”)

I hoped that I had wrapped up the series, because talking about church is… challenging. But as I’ve reflected, I realize that I left something out.

And what I left out has, in fact, come to shape my entire relationship to God and God’s Body, that is, the bride/whore of Christ. (As someone once said, “The church is a whore and she is my mother.”)1

I’ve come to believe that, before I left evangelicalism, I was codependent with the American Christian church. And that has changed how I engage the church today.

But before I explain what I mean, I want to define codependency.

You can understand a lot about codependency from its origin story: in addiction support groups in the 1980s, therapists noticed a trend among an addict’s intimate relationships. Someone close to the addict would often participate in the addict’s addiction by proxy, supporting their habit by trying to minimize social and behavioral consequences for the addict through highly effective care-taking. So a wife might cover for her addict husband’s absence at a social event. Or a parent might allow an adult child who is abusing alcohol to live in the basement rent-free, shielding the child and others from a consequence of their addiction that could, perhaps, encourage the substance abuser into recovery. Or a teen might take on additional housekeeping responsibilities because a binge has caused their parent to neglect tasks he/she normally accomplishes.

Essentially, codependency is a “dysfunctional relationship dynamic” in which one member in the relationship takes and the other gives ad nauseum until the giver collapses in a heap of mental anguish and resentment due to upholding the burden of the relationship all by herself with no help from the other party—and meanwhile, the natural consequences that could encourage healthy growth and change in the other party are mediated and carried by the over-functioning of the giver.2

Friends, I am this overachiever, over-functioner.

I was class president every year at my Christian high school. I took over group projects because I could not stand a grade less than an A. (An A- felt like coming in third place; after all, I could’ve gotten an A+!!!) Before an untimely move my senior year of high school (a story for another time), I was in the running for drum major, yearbook editor-in-chief, and valedictorian. And I also hyper-functioned in relationships, starting at home with my family. If at all possible, I will carry the world on my shoulders or die trying.

When I first entered therapy at age 21, learning the word “codependency” explained so much about me. I had developed (inherited?) an insecure attachment style, a learned role in my dysfunctional religious family structure. As the oldest girl, I played mother more often than not, even for my parents. This is how I learned to cope with the dysfunction of my family relationships. And then I transposed the pattern onto my other relationships, too, where I aimed to become indispensable—even if that meant I suffered. I was a codependent.

Now, obviously, codependency is a relationship term about a relationship amongst people, most often family members. So, what does it have to do with church?

Well, humor me by joining me in a thought experiment.

Picture yourself entering the sanctuary of a new church for the first time. You’ve never attended this service before, but you spent the night before scrolling through an online directory, and you’ve decided to spend Sunday morning here.

You settle into the pew/chair/bench with a mug of coffee in hand. The organist/choir/band is warming up, and the people seated around you seem nice enough—at least they’re willing to make eye contact and smile wanly. So far, so good…even if this church’s coffee does taste burnt. (A strike against the hospitality team, but you can always bring your own.)

Then the service begins. You start to notice other flaws. That vocalist’s mic is far too loud and she’s a bit off-key. (Is she also barefoot?) The pages of the order-of-service have been stapled in the wrong order, causing a delay in your liturgical recitation, and you fall behind. Worse, the hymn everyone is singing is not printed in the bulletin, and you realize too late that you were supposed to rummage around in the seat back pocket at your knees for a tattered hymnal. (Of course, you turn to the right page just as the singing ends.)

The preacher—whose style reminds you too much of the most annoying “cool” Gen-X internet preachers—alludes to politics from the lectern, and you wonder how often policies and politicians and patriotism come up in sermons, and if they do, to what side does this preacher and their congregation lean? You did notice a gaggle of Teslas in the parking lot.

Or perhaps the preacher refers to “traditional faith” or “accountability partners” or “covenant theology” or some other coded language that reminds you of your conservative evangelical past. Or the entire congregation is an ocean of blue hairs, not a drop of melanin in the pew, and zero babies babble in the aisles. You wonder if they even have a youth group for your middle schoolers.

Then again, amid the questionable performances, pew mates, and sermon, perhaps you experienced God at this service. A reader has delivered the Scriptures out loud with passion. The prayers have expressed what you think are the tones of genuine faith in congregants or church leaders, and the liturgies have fed you. Plus, you have heard that the church offers substantial social services to their nearby unhoused neighbors, and they have history of civil action on behalf of BIPOC Americans. And your good friend attends and you’d really enjoy seeing them weekly! (Plus someone to sit next to!)

Okay, if I’m at this service, I leave scratching my head with a two-part question circling my mind: at what point should I walk away? And what would make me choose to stay, despite the problems?

Perhaps you were the type to never walk through the door in the first place, or you would have walked out at the first hint of the remnants of evangelical culture. Then again, if you’re like me, you could be the type to disassociate and sign up for everything that very second because DAMN, this church needs help, and I’m good at helping.

I have almost never known how to answer the first question. (Walk away? What’s that?)

I have committed too quickly, stayed too long, exposed myself to too much hurt, ignored red flags because I wanted to “try to change” cultures or leaders that never wanted to be changed in the first place.

And I have called this faithfulness.

And it hasn’t helped that I once received specific teaching from a pastor who told Jeremy and I that if we left his church for any reason, as a “covenant partner” (i.e. member), I was breaking my vow to God… because apparently, when I signed my signature to the statement of faith/membership agreement, I had surreptitiously been married to the institution of that church?? Obviously this was entirely made up— joining the roster of a church is NOTHING LIKE marriage. (So, yes, my family and I divorced that church…)

But I am also prone to this sort of behavior. I am both loyal and codependent by nature, so I have felt confused about how God wants me, as an individual, to relate to both a particular church and to the capital C church.

The Bible is unclear about what level of commitment a particular Christian should have to a particular institution—when Jesus overturns the tables in the temple, is he trying to say that we should throw out the entire system of temple worship and sacrifice because the religious institutions writ large are corrupt? Or are we supposed to replace temple with church service? And if we’re supposed to “share everything in common” and “not give up meeting together,” does that translate to a second marriage to the local congregation? Does that translate to undying loyalty to one pastor? Is a specific church a stand-in for Jesus, my heavenly groom?

Or am I meant to give my loyalty to the capital C Church, the wide, universal, expansive collection of believers across time and space with whom I will worship at the end of days? (I’m the spleen, by the way, in the body analogy.) What does loyalty to the church actually mean? And do these ideas that have been so widely believed by evangelicals, in fact, have anything to do with the idea of ”church” as Jesus meant it?

What Jesus does say about the local church is spoken in metaphor. The church Christ’s bride (a metaphor, by the way, not literally true, Jesus does not suggest here that we will be sexual partners with Jesus in heaven…*rolls eyes in Joshua Butler’s direction*).

The apostles are more practical. They say, look out for each other, spend time together, stop speaking over each other in services, don’t preference one leader over another (no celebrity pastors, AHEM), and for the love of God, stop the affairs in your midst. We are meant to remember Jesus when we eat together, and we are meant to share the good news of God’s arriving kingdom—over and over and over.

So far, that does not sound like any specific church has a claim on your undying loyalty. Instead, I interpret these words as God’s desire for God’s people not to be faithful to an institution, but to particular people. “Church” is people—not a building, an event, a 501(c)(3), or a leader. “Church” is the people who love Jesus and want to live Jesus’s story together. And “meeting together” does not have to be as formal as a service, though I would suggest that meetings should happen regularly, if only because you and I are forgetful beings.

Receiving the eucharist, reciting liturgies, serving others, and reading/listening the Scriptures aloud while seated in the same room as other followers of Jesus does matter. It forms our thinking and our interior narratives.

But do you have to go to the same church service every Sunday to practice remembrance? Nah.

Our primary loyalty should be to Jesus himself—and to the people who represent him to us. We are formed more deeply by the people with whom we share ourselves. An event cannot compare to these deep relationships. Journeying alongside others who share your commitment to Jesus and who are committed to you, we can practice the rhythms of church communities. In spiritual conversation—confession, prayer together, and storytelling—we can practice the way of Jesus with the same sacred remembrance that we once believed only belonged to organized, institutional expressions of church.3

In practice, this can look many different ways, but I’ll tell you how it looks for me: I still attend church, but not just one church. I am currently courting 2-3 churches, jumping from one to the other (with no real rhyme—I’m a feeler, so that’s how I’m making this weekly decision). I have spread out my worship, and that’s working for me right now.

Meanwhile, I have many deep friendships—with my husband and a handful of close girlfriends. These are sacred relationships where I can share my whole self, including my envy, pride, fear (which often looks like disassociation), anger, lust, acedia, etc., etc. If you know me IRL, you know I’m not one to hold back. I often ask my husband to pray for me when I feel I need it, and in one season of my life, I was regularly asking friends to pray for me daily, too, whenever I felt anxious or depressive. I am on the hunt for a spiritual director, but have not found one yet. (Sigh. If you’re in Colorado and have recs, I WOULD LIKE THEM, PLEASE!)

I also have several female pastor friends to whom I feel I could go to receive pastoral care, as needed. (You probably know who you are, and I hope you know that I love and like you so much.)

My method here is scattershot, and I admit that my conclusions may change. I used to believe that belonging to a spiritual institution was vitally important and could not be replicated by any other means.

But as a recovering codependent who has so often believed my job in my congregation was to fix the churches I had joined (and probably to fix their leaders, too), it’s a relief to say, fixing the church (and the capital c Church) is not my job. That’s Jesus’s job. That’s the Spirit and the Father creating and recreating the Body they made in the first place.

(BTW: since our own physical cells regenerate every seven? eight? years, why not also the Body of Christ? Shouldn’t we expect the same amount of change in that Body as in our own?)

And lately, I’ve felt a deep rest and peace at church that I have not felt in years. When my only job is to remember, and to remember in deep community, I have found that I can experience genuine joy at church. For me, for now, that’s enough.

Thanks for reading this tender narrative with empathy!

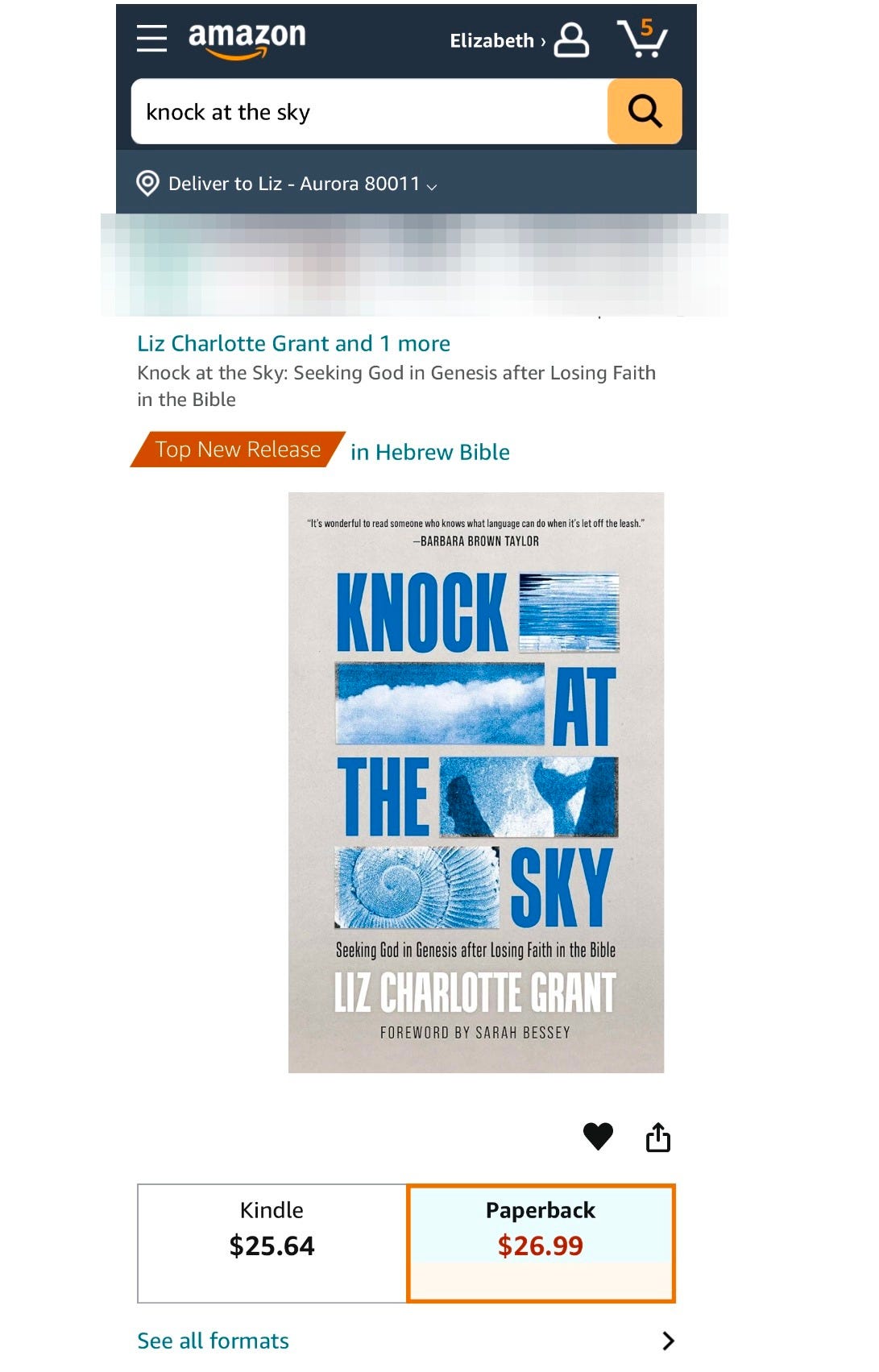

And thanks also for a really surprising and joyful week of preorders for my book—I somehow managed to sneak into one of Amazon’s very specific top release categories last weekend. (Scroll down for a hearty chuckle.)4 I’m deeply grateful that you have become part of my spiritual community, too, reader pal. You are a gift to me.

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

How have you navigated church dysfunction? Are you attending church at the moment? Why or why not? Tell me all about your church journeying.

Here’s the rest of my “returning to church” series, ICYMI:

Notes

No one can agree on who said this, but I’ve seen this quotation attributed to St. Augustine, Martin Luther, and Leo Tolstoy. If I had to pick between the three, I’d pick Tolstoy.

From Psychology Today: “Codependency is a dysfunctional relationship dynamic where one person assumes the role of ‘the giver,’ sacrificing their own needs and well-being for the sake of the other, ‘the taker.’” They continue to describe how it has become “shorthand for any enabling relationship” within the spheres of pop psychology. Many psychologists doubt its helpfulness for how it “pathologizes and stigmatizes healthy human behavior, particularly behavior that is loving and caring.” While I respect the concerns of these providers, I have found for myself that the language of codependency is illuminating and helpful for highlighting the lax boundaries I developed in my growing up years and for how it has illuminated ways to break out of enabling behavioral patterns.

Re: the communion table: can you tell I’m not a sacramentalist? My Anglican readers will take me to task on this—because you CAN’T DO THE EUCHARIST IN YOUR HOME BY YOURSELF. You need a priest to make the bread and wine sacred. They’re not wrong. But, in my humble opinion, they’re also not entirely right… ;-) I believe the heart with which we approach the sacrament of eucharist matters more than the ritual. Because remember, so many of us women have been denied the opportunity to hold roles that would allow us to bless the sacred meal. And so who’s to say that God’s mercy does not allow us, too, to turn ordinary wine and bread into remnants of God—if only we ask the Spirit to intervene?