the Empathy List #97: Ask Better Questions, Pt. 2

Harry Potter and Fundamentalism

This is part 2 of a series on asking better questions & cultivating curiosity.

Hello friends, Liz here.

Today we’re talking about Harry Potter in order to talk about religious fundamentalism. (I promise it’ll be more fun than it sounds. ;-))

But first, a reminder from my last email: the practice of curiosity requires asking open-ended questions.

And by open-ended question-asking, I mean asking questions that produce answers you don’t know yet, answers that might surprise you, answers that could even prove you wrong.

As I hinted at, religious fundamentalism has often found such openness threatening.

I was planning to breeze past this point in this email series—because for me, it feels wearying to keep returning to these ideas—but I’ve realized that it’s an essential piece in cultivating curiosity in ourselves, and it’s not a given that anyone else has nudged you this direction. So I’m going to address it.

First, I want to say that us religious folk aren’t the only fundamentalists. Any version of fundamentalism across the spectrum (from liberal scientists to conservative pundits) can strangle curiosity about people or ideas because, in order to be surprised, to learn, to change our minds, we must take down the gutter guards. We must risk traveling outside of the norms our group has agreed upon and walk into challenging terrain that even opposes what our tribe stands for. This is risky both intellectually and relationally. This is also why empathy is such a trying discipline to practice—there can be great losses that come when we decide to open ourselves to another way of thinking. We might actually walk away a different person.

Yet for me personally, my primary experience with fundamentalism is the religious kind. So, in order to find a way in to talking about my own experience of religious fundamentalism, we now turn to everyone’s favorite children’s book series.

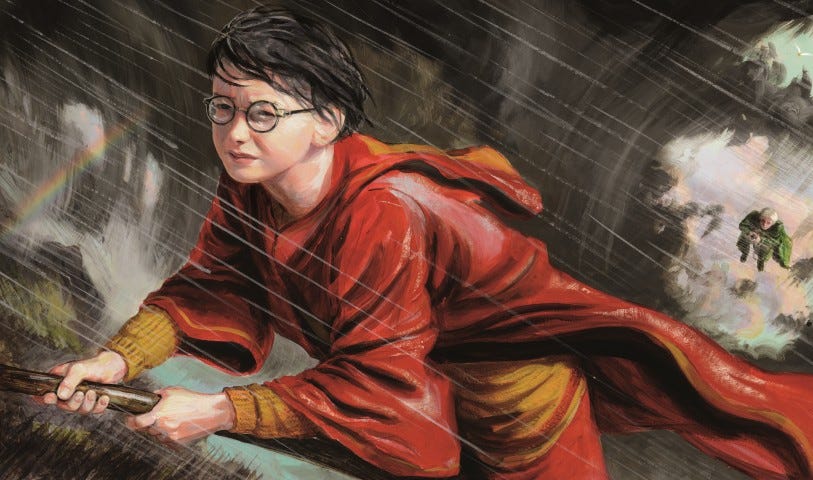

I’m talking about Harry Potter.

Like many evangelical kids, I was not allowed to watch or read Harry Potter—because of witchcraft, duh—so I only picked up the books as an adult. I had just birthed my first child in my living room with the help of a couple of midwives and I was still spending the majority of my days seated on a pillow. My major outings were to the bathroom, the kitchen, and slow strolls around our block after my husband, Jeremy, got home from work, him pushing the stroller as the light drained from the sky, me shuffling behind.

When the evening breastfeeding sessions extended into unending clusterfeeds (“the witching hour…”), we picked up the first book from the library. The two of us were in our twenties, and the whole series, including the movies, had already released years before (Part 2 of the Deathly Hallows movie had released in 2007, and this was 2012). We were very late to the party.

Jeremy read aloud to me while I balanced my daughter on my chest, all three of us in the leather armchairs I’d inherited from my parents when he and I had married the year before, and we got lost. It felt a relief to live another’s life for a moment, amid the diaper changes and 3AM wake-ups.

We could not claim the books from the library fast enough--although when we reached the moment in book 6 when Dumbledore...1 [spoiler footnote placed here exclusively for my friend Sarah who writesWild + Wasteplus any other kids of evangelicalism who haven't made time to read the series for the first time yet], I made my husband look up the ending to the series on Wikipedia.

I had been muddling through undiagnosed postpartum depression and anxiety, and so it felt urgent to protect myself, even from the threat of disappointment in fiction.

“I need to know whether Harry lives or not,” I told him, “If he dies, I just can’t.” I needed it to end well. I needed Harry to make it through, just as much for me as for him.

At the time, I remember that a co-worker of my husband’s, an avid fan of Potterworld, expressed jealousy that we were experiencing Harry Potter for the first time. Personally, she would do anything to go back to her first reading, the first time she joined in the adventures of the boy who lived.

I understand what she meant. Having now read the series a dozen times, with copies of my own on my bookshelf and the audiobook editions to boot, I myself have become a Potter fanatic. I reread the books when my second child arrived during that same postpartum period (mostly in bed while I was supposed to be napping and was really avoiding my energetic toddler), and I have made a habit of rereading the series whenever the malaise of the winter holidays settled on me and I felt a deep loneliness at being separated from my family-of-origin relationships.2

I know it’s unpopular to like Harry Potter at the moment because J.K. Rowling has come under scrunity due to her trans commentary (earning her the TERF label). I believe that critcism against her is justified… and also, sometimes, works of art transcend their makers. This usually happens with the words of men, but for me, it’s happened with Hogwarts.3

Harry Potter, to me, has become a family member. The series has offered me comfort, familiarity, safety. It is predictable, it ends well, families are mended and remade. The sad things come untrue. (This isn’t a spoiler cause it’s a childrens’ series… so OF COURSE it ends with happily ever afters).

Personally, I tear up every time Severus Snape, the most hated character, reveals his tenderness to Harry at the time of Snape’s death. I’ve found it to be one of the strongest cases I’ve ever read that no one—no one—is a hopeless case. And it’s fiction.

Of course, the irony of my affection for the Harry Potter series is the fact that many in my evangelical tribe are certain that the series is evil.

As I said, my parents did not allow me to engage with any Potter media whatsoever in my growing up years. My family was moderate when it came to media consumption, not buying into the entire Christian consumer enterprise and its cancellation machine. Even so, apparently my parents heard enough Christians they respected say bad things about the series that they believed the negative hype. And if there was a chance that Harry Potter might corrupt my siblings and I, they wouldn’t risk it.

The fervor against the series was intense. Evangelicals—joined by conservative folks across tribes—performed book burnings, wrote theses and produced documentaries on the devious nature of J.K. Rowling’s aim to make witches out of our children, and even sued to keep the books out of Georgia’s public school libraries. All this despite Rowling being a Christian herself and imbuing the books with overt religious themes (resurrection, unconquerable love, loyalty, friendship, truth, good and evil…).

A great example of the thinking that undergirded this mania against the books can be found in a review of the first Harry Potter movie, “The Sorcerer’s Stone,” published in Focus on the Family’s entertainment review site, “Plugged In”:

“…Even if Harry Potter‘s magic isn’t of the occult, it still carries with it serious dangers. First, Rowling’s stories—unlike Lewis’ or Tolkien’s4—are neither a Christian allegory, nor do they subscribe to a consistent Christian worldview. And second, we live in a culture that glorifies and promotes witchcraft and the occult. No matter what the essence of Harry’s magic, the effect of it is undoubtedly to raise curiosity about magic and wizardry. And any curiosity raised on this front presents a danger that the world will satisfy it with falsehood before the church or the family can satisfy it with truth. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone definitely raises those curiosities.”

I want to point out a key sentence above: “…any curiosity raised on this front presents a danger that the world will satisfy with falsehood before the church or the family can satisfy it with truth.” Oof.

Essentially, the reviewer is arguing that curiosity itself is dangerous, and so exposure to ideas that have not been santized and vetted by book banning watch groups could put children into danger. This danger wasn’t physical, not right away, but spiritual. Ideas themselves can destroy. This is the famed evangelical “slippery slope.” If you transgress the Christian norm, even a little bit, even by accident, you may be in danger of eternal consequences.

I am also struck by the loneliness implied by that key sentence: the danger for children is so insidious that it cannot be counteracted in time before it does damage, not even if you are sitting next to your child on the couch as they watch the movie with you. No after-the-film family discussion will suffice to diffuse the danger. The effects of consuming such media are instantaneous and essentially unconquerable. Your presence, as the caring parent, matters not at all, makes no difference. There is no answer, then, except total abstinence.5

I hardly need to tell you that this is an extreme exaggeration. No movie has eternal power over anybody’s soul, not even the most vulnerable and underdeveloped among us (I’m looking at you, babies). And parents have major influence in shaping how their children perceive the meaning of a film, a book, a conversation between classmates or grandma.

Yet the fear that undergirds these statements is very real.

Have you ever been told that curiosity is dangerous? That the tiniest glance over your shoulder can have the most serious eternal consequence?

The metaphor that comes to mind (was I taught this? Or just associated it?) is the story of Lot’s wife, who looks back over her shoulder at the firebombed cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. Because of her longing back gaze, poof, she immediately turns to salt. The story seems to support the idea that it takes only one glance in the wrong direction to incite the wrath of God.

What I’m getting at is that reviews like the “Plugged In” review above underlie an evangelical existential terror. But, I wonder, who invokes their terror more—J.K. Rowling or God? I’d say, in the world of this reviewer, God is the dangerous one, a violent Deity who is looking for any excuse to blast you or your children with the lightning bolt already cocked in his fist. Just give me a reason to blow you to hell, this God seems to threaten.

Is this really what God is like?

As you may remember, I’m in the process of finishing up writing my first book (read about it here) :-D, and one of my main sources in studying this section of the Scriptures has been the Jewish legends of the rabbis, often called the Haggadah.

I’m using this text instead of a commentary by John Calvin or his ilk because, frankly, I’m dead tired of the way evangelicals have read the Bible and it doesn’t work for me anymore. Also I don’t want to take the words of these dead (likely) white supremacists6 to heart… even if they are “technically” right about what the Bible means.

But I still deeply love the Scriptures. I’m looking for a way to read them that feels true to my more open-ended faith. And actually, despite how they’ve been misused and distorted, they’ve still shaped me… just like Harry Potter has. (GASP! J.K.’s evil plot worked! Bahaha)

Among these more imaginative Jewish takes within the Haggadah, one story has stuck out to me. This rabbinic legend recounts a conversation between Moses and God. As Moses is copying dictation from God, who is relaying the creation of the universe into words, they hit a snag:

“When [Moses] got to the verse ‘And God said: “Let us make Adam”’ (Gen. 1:26), Moses dared to ask, ‘Master of the universe, why do You give heretics their opportunity?’ ([For] they will say there are numerous deities) ‘Write, O son of Amram,’ God replied: ‘Whoever wishes to err, let him err.’” (R. Samuel bar Nahman in the name of R. Jonathan)7

Whoever wishes to err, let him err.

This for me has started to become a bit of a mantra, a prayer to help me undertake the intimidating task of writing, essentially, an artful commentary. I have, at moments, felt terrified that I’ll do it wrong, that I’ll get God wrong. I pray that my words encourage and not discourage deeper faith and committment to God. But sometimes I fear that my engagement it TOO wide, TOO open-ended. Will I leave my readers flailing?

In those moments I return to these words attributed to God: Whoever wishes to err, let him err.

To me, this legend does not so much excuse being wrong, per se, but instead allows elbow room for exploration. Here God spells out just how unlimited humankind’s autonomy really is. We can both pick how to engage with Godself and with the story of God. God is not controlling the narrative.

In this legend, God seems to be saying, risk being wrong in your pursuit of what is right. Because the pursuit is what matters more.8

Now, duh, legend is not the same as divinely inspired speech. But this story jives with another of my favorite theological ideas: all truth is God’s truth.

This is the idea that we never need to fear seeking out the truth--whatever's at the very bottom-- because truth and God are always on the same side. (Ironically, John Calvin affirmed this idea, which he stole from Augustine.) Jesus puts it more succinctly: “I am the truth” (John 14:6).9

From this, I see that curiosity and truth are cousins. Truth is the noun, and curiosity is the verb, the key required to unlock the truth.

While “curiosity” as a discipline has often been labeled by Christian fundamentalists as “evil,” the truth is that curiosity is neutral. You can, yes, be curious about evil. But also, your curiosity can be a form of genuine seeking, of pilgrimage, of that lifelong hunt for evidences of God in all places, as many of the early scientists were.

Personally, I can attest that my curiosity has led me into greater devotion. In my studying and exploring and questioning and reading and watching and observing, I have sought to become attuned to God in all things—not in a pantheistic the trees contain the essence of God so must be worshipped them, but in acknowledgement of God’s imprint on the entirety of God’s creation.

Curiosity does not have to be antithetical to God, but can actually facilitate encounter with God. Curiosity leads us beyond our material lives and toward the transcendent.

In wide-ranging exploration, we encounter God, too. God is not only in the tiny evangelical box, but outside, too, grabbing the attention of anybody who’s searching for divinity. Because Godself is always seeking us first. That’s why Jesus speaks so much about lost and found things. Picture God on hands and knees, running God’s hand over the carpet in search of whatever God lost: that’s you. You’re the pearl of great price.

I believe this is God’s way of offering us permission to seek—full stop, no exceptions.

It won’t surprise you to learn that currently, my children, husband and I are reading Harry Potter. Together. Via audiobook. We listen in the car on the way to school and we listen in the evenings, usually while munching dessert. (We parents are not above bribing our kids with candy to get them reading…. ;-))

We just completed book 6, making it through the same conclusion that had me spinning when I first read the series. Yet despite feeling the creeps a few times and some serious suspense on the characters’ behalfs, my 8- and 10-y-o have had zero nightmares and zero desire to learn how to summon dead bodies to act as their zombie army. (Phew.)

Instead, in the course of our reading, we’ve had transparent conversations about grief, about evil and goodness in real life, about the complexity of each human person. We’ve talked about the soul—what is it? Where does it live inside of us? Why does it matter? And by the close of the last book, I’m betting we will have talked about resurrection, too.

Though it’s my bajillionst time reading it, I’m finding myself moved all over again in seeing the face of God appear in the shape of Harry Potter. Who would have thought that a childrens’ book could become a tool for devotion? And what could be more Christian than that?

Thanks for reading.

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

P.S. I stumbled on two Harry Potter tangential reads that fascinated me.

#1 A fundamentalist mom rewrote Harry Potter to make it Christian enough for her kids …and it’s pretty wild. Harry goes to School of Prayers and Miracles and there’s a definite christian nationalist bent near the middle. Have fun!—FanFiction.Net

#2 Meet the graphic designer who made everything from packaging for Weasley Wizard Weezes products to Ministry of Magic pamphlets and posters for the films. —Harry Potter Fan Zone

Footnotes

…soars off the edge of Hogwarts castle to his death…

Eventually, this story of family distance will become a published memoir. In the meantime, I have written briefly of the distance between me and my family-of-origin elsewhere, so I won’t belabor the point in this particular email. However, if you’re interested in revisiting my story, you can find it here:

“How Scripture Helped me Set Healthy Family Boundaries” at US Catholic

And here:

It’s okay if you disagree with me about this. I’d love to hear from you, in fact. Tell me if I’m getting it wrong! Your voice is valued.

Tolkein and Lewis are the good guys of fantasy. Orcs? Totally cool. Death eathers? Demon children-eaters.

Geez, this sounds familiar. No dancing cause dancing leads to sex, amirite?

Too honest? For a thoughtful and nuanced take on John Calvin within the African context (by an African), read this scholarly piece: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/43167516.pdf

This is from my new favorite book which is blowing my effing mind: https://www.amazon.com/Book-Legends-Sefer-Ha-Aggadah-Midrash/dp/0805241132. I want to be buried with this book so I can never be without it (Jeremy, take note).

It is also true, by the way, that the entire Talmud, the legal writings of the rabbis that make sense of the Law of God, is meant to be a “fence” around the Law, often going above and beyond to protect the Hebrews from transgressing (They were the ones who decided that “no work on the sabbath” was not clear enough; instead, we get “don’t walk more than this many steps on the sabbath”; not “don’t cook,” but “don’t even light a fire”).

Yet I’d argue that the very culture of the Jewish scribes—those men that copied and often revised the Old Testament—that occurs in Jewish Torah teaching is a culture that encourages exploration.

Jesus also said, in John 16:13, “…When the Spirit of truth, comes, the Spirit will guide you into all the truth…”