The Empathy List #96: Ask Better Questions, Pt. 1

AKA How to Know Another Person

If you believe in my mission of a more curious & empathetic Christianity, please consider subscribing for $21/year (normally $30/year).

Hello friends, Liz here.

Part of my plan for this newsletter in the new year is to write more to the theme of curiosity. But before I start subjecting you to my weird research projects 😉, I suppose I should explain why I find curiosity so essential to the life of faith.

(Because I’ve certainly gotten my share of strange looks when I start rambling to friends about what I’m currently writing… and they don’t want to offend me by asking, but why tho?)

Central to the practice of curiosity is the ability to ask open-ended questions.

By an open-ended question, I mean a question that produces an answer you don’t know yet, an answer that might surprise you, an answer that could even prove you wrong.

When we ask questions like these of other people, the answers lead us into deeper emotional connection because they force us to think more deeply about ourselves and to listen deeply to another. In contrast, “yes or no” questions tend to shut down conversation, as they seem to discourage expounding further.

Yes/no questions that I might ask my kids: Did you enjoy your day? Were your friends kind to you today? Have you finished your homework?

Open-ended questions that I might ask my kids: What did you write today in literacy class? What was the funniest thing a friend said to you this week? Which Star Wars character is your favorite and why?

Can you see how one set of questions (above) will encourage my kids to tell me more, and in contrast, how the other has assumptions already built in, a particular answer I’m looking to hear that could shut down contrary answers?1

For children, open-ended questions affirms their autonomy and affirms their individual thoughts and experiences, which is vital for them to develop into healthy adults. It encourages them to think for themselves and teaches them how to develop meaningful relationships.

For grown-ups, asking open-ended questions of our children helps us continue to learn the ways that our kids are growing and changing, which is a continual process (as it is for all of us). It also reminds us that our kids are individuals and not extensions of ourselves (as we might be tempted to think).

Some of you might consider these musings on question-asking as basic, even insultingly obvious.

Yet I have realized in the course of attending therapy over years just how rare it is to want to know another person.

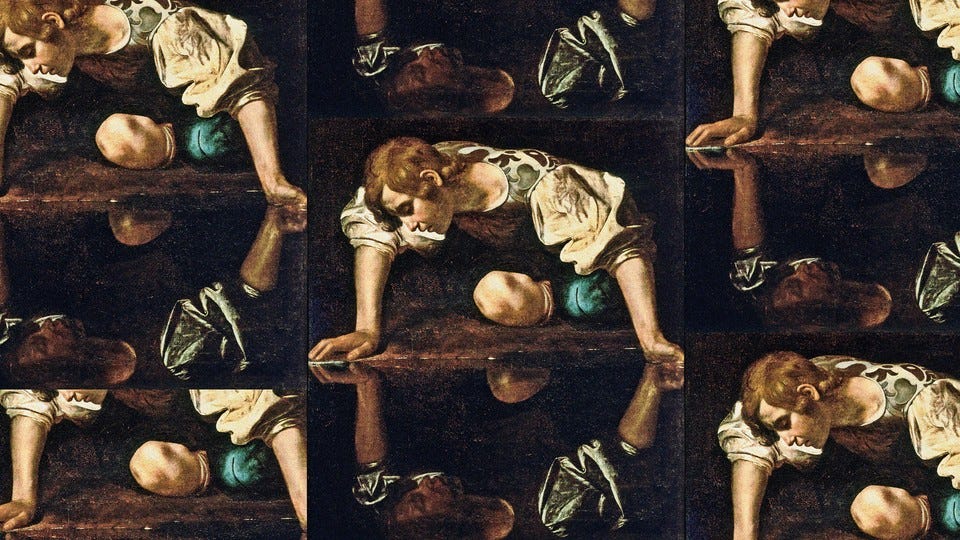

Call it sin if you will (the curving in on oneself, incurvatus in se, as described by St. Augustine), but every human posesses a natural narcissism by which we desire only to know ourselves. Or, worse, we may acknowledge the other only to reject the other, deeming him or her unworthy of our gaze.

Which is to say, the natural proclivity of each human is to stare only at our own selves, first and forever, like Narcissus in love with his own reflection.

Yet not only is the desire to know “the other” absent, but also the skill to know is absent.

So it is also rare to actually know another person. The majority of us do not come hard-wired with an instinct to draw out information sensitively from others. Even if we do experience great loneliness and desire to be known or know others, we may have never have been taught how to meet our need for connection.

This is where I feel I have something to offer you. Because I do have a greater proclivity toward the sort of question-asking described.

Generally, women are more likely to ask questions than men are, simply based on gender norms within the workplace and in close relationships.

Yet, in my case, I have a hunch that having a background of complex trauma has also offered me a leg-up. Though I cannot confirm it, I have often noticed that being raised in a dysfunctional home has made me extra-sensitive to the needs and feelings of those around me. This higher sensitivity helps me respond minutely to their moods and thoughts as expressed in their bodies, as a way of protecting myself and others. It’s a sort of traumatized kid’s survival mechanism.

For those like me, being attuned to our dysfunctional families-of-origin offered us more control of our environment and relationships (minimally more). Now, as adults, these skills are applied unconsciously and more broadly to a whole range of relationships, for good and ill.

In this season of my life, I’ve discovered this sensitivity to be a true superpower. And Jesus has been my model in learning how to apply these skills in love (and not in furthering my own self-interest).

Throughout this ministry, Jesus is always asking direct questions of his followers. He asks:

What do you want? What do you want me to do for you? Do you understand what I have done for you? Do you believe? Who do you say that I am? Why are you so afraid? Why did you doubt? Why are you crying? Will you give me a drink? Has no one condemned you? Do you love me?2

In each of these instances, Jesus sees the deeper need of the human before him. His question acknowledges their inner state and invites them into self-revelation by means of a question. Because that self-revelation is witnessed and spurred by Jesus, these questions also strengthen the person’s relationship and trust in Jesus. And ultimately, Jesus becomes the answer to their need, as they discover by engaging Jesus’s insightful question set to them.

Evangelicalism has not always encouraged such open-ended exploration within its history (for example, our wariness toward psychology). Yet Jesus’s question-asking is an obvious counterpoint. If questions are not untrustworthy inherently, but rather can lead us toward truth, then we have nothing to fear because all truth is God’s truth.

In addition, I believe that open-ended curiosity and attention toward the other is, in fact, the best way I can love my neighbor as myself.

Deep listening and question-asking are discipleship skills that can and should be learned as a practices against selfishness and toward love. Because open-ended question-asking is the key to knowing the other and also knowing ourselves. Such a posture cultivates humility, growth, and yes, curiosity—in other words, surprise.

Since God loves to dwell in surprising places, I see this, too, as the means by which we encounter grace. So when you practice opening yourself to surprise, you might also stumble on God, too.

Thanks for reading.

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

I edited out a whole section here about how to ask open-ended questions, but it just didn’t fit. So, more on that to come!

“What do you want?” Jesus asks two of John the Baptist’s followers who are trailing him (John 1:38).

“What do you want me to do for you?” Jesus asks the blind men who call to him from the side of the road (Matthew 21:32).

“Do you understand what I have done for you?” Jesus asks the disciples after he washes their feet at the Last Supper (John 13:12).

“Do you believe in the son of man?” Jesus asks the man born blind (John 9:35).

“Who do you say that I am?” Jesus asks Peter (Matt 17:15).

“Why are you so afraid?” Jesus asks the disciples as they cower in the boat (Matthew 8:26, Mark 4:40).

“Why did you doubt?” Jesus asks Peter as he fails to walk on water (Matthew 14:31).

“Why are you crying?” Jesus asks Mary outside of the tomb after the resurrection (John 20:15).

“Will you give me a drink?” Jesus asks the Samaritan woman at the well (John 4:9).

“Has no one condemned you?” Jesus asks the woman caught in adultery (John 8:10).

“Do you love me?” Jesus asks Peter on the beach after the resurrection (John 21:15).

Jesus was such a skillful questioner, I think curiosity like you say is the key. Mostly when I assume I know what's going on I fail to ask questions and I continue rightly or wrongly in my assumptions. Its lazy for the most part. Attentive communication is much more skillful than i imagined. I too have that heightened sensitivity from childhood and I have found it such a burden until recently when I added in a few boundaries and respected my limits.