The Empathy List #166: Christian Celebrity Betrayals

How do we respond when Christian celebrities (like Dobson and Elliot) fail us?

Hello friend, Liz here.

Last week, I examined how and why Dr. James Dobson’s name appeared in the Epstein Files. Many of you read it with gratitude and tenderness. (Thanks for that.) But as you might imagine, not everyone enjoys hearing that their heroes have failed them.

I learned this firsthand when I published an essay two years ago about Elisabeth Elliot. (Here’s the original essay and how I responded to its virality… which came with a lot of criticism, as you might imagine. Currently, the article ranks third on Google search results, just below Elisabeth Elliot’s own foundation website.)

I had never before published anything read so widely. I still haven’t replicated those reader numbers, and I doubt I ever will again. But that experience gave me an intimate understanding of the parasocial relationships that Evangelicals have with their celebrities.

Elliot was a difficult person who tried to do what was right amid an unbelievably difficult and unbelievably charmed life. She was introverted and strident. The missionaries who worked closest with her didn’t like her.

Yet she sold millions of books and spoke to millions of evangelical Christians across the globe, garnering a reach beyond the wildest hopes of any Christian author today. Her readers accessed her content across mediums—in person, on the page, online, and on the radio.

Early in life, she was ambitious, and her publication record proves it. But as she aged, she lost that spark. It was her third husband who made the Elisabeth Elliot empire. It was also her third husband who abused her.

As a writer, Elliot colored in the lines and reached the widest swath of Christians. Her writing was bland, but still retained a tone of intimacy. She told personal stories, her love stories, in fact. She did not claim to be a theologian, but engaged the Bible from the heart.

All of this made readers feel like they knew her. She became aunt, mom, grandma, and sister to her readers, and they treated her advice like scripture.

(By the way, I’m not exaggerating when I say they treated her words like scripture—I heard this directly from Gen-X and Millennial women after the essay published. Many learned Elliot’s words as the one and only dating rules from their Boomer evangelical parents. Elliot’s advice was treated with the same reverence as the Bible itself, a book which happens to contain nearly zero advice pertaining to twentieth and twenty-first century dating norms.)

Anyway, when my writing arrived in the feeds of those who had adopted Elliot as matriarch, these readers were, um, unhappy. Not with her, but with me. They wanted to silence the messenger. Folks called me names, people assumed I had a “vendetta” or that I only wrote this to make money (I’m sorry, did you think writers write for the money?! LMAO), and several people made sure to tell me that I was fat. (Which I am, …so, what else you got, Chad?)

Fortunately, there was no way in hell my editor would have considered pulling the article. (The web traffic alone!) But I’d also done my homework, including an interview with one of the authors I quoted extensively, and my essay was in fact a review of two recent biographies (not my research). So, though they hated what I’d written, my detractors had no evidence to make a case for libel. I never heard from the Elliot foundation (or if my editor did, he never told me about it). I’d guess the foundation is still determinedly avoiding the entire thing, hoping the story will disappear.

So sorry, Meg Basham, no dice, you just gotta deal with the facts:

Elisabeth Elliot was abused by her third husband, and for that reason alone, what she taught about marriage, family, and complementarianism must be reexamined.

I feel a similar way about the news relating to Dr. Dobson’s appearance in the Epstein files. Of course, some evangelicals want to respond in a similar way as they responded to Elliot’s news.

They’ll discredit the messengers. They’ll say that just because one evil person read or shared his work, doesn’t mean the work is garbage, and certainly doesn’t invalidate a patriarch’s legacy. They’ll say that it’s a smear campaign without basis in reality, and then if they’re imaginative enough, they’ll rewrite reality in a few sentences.

(Case in point: read these comments below Daniel Silliman’s reporting at the Julie Roys’ Report.)

But this is another fact: when you search for James Dobson within the Epstein files, you will find that James Dobson.

And that’s disturbing. If it doesn’t disturb you, if you have no curiosity about why Epstein would have read and shared Dobson’s work, then I’m not sure we have enough common ground to have a conversation.

I can tell you that if my own work were being used as a tool of perpetrators, I would care. I would want to know, and I would want to reexamine my theology. I would want to pull books and disown the perpetrators in the strongest terms.

The Bible tells us that leaders will be judged more harshly, that what we teach and how we lead holds more weight in the eyes of God. “If one person stumbles,” in fact, leaders should chuck themselves into the ocean, should dig their eye out of its socket just to make things right again. Jesus says that those who lead others astray intentionally, for the sake of their own power or wealth, they should fear for their own salvation.

I admit that this judgment language is tricky for me. I cannot claim to understand it. But I can tell you that whenever the Bible slings a “woe unto you,” I want to attend, and I want to respond.

It really does matter. It matters who claims us and our teachings. And I will do everything in my power to make sure my words do good and not evil. I would hope that if Dobson was actually the man so many evangelicals believe that he was, he would do the same.

Adulthood contains so much disillusionment. Every evangelical, former or current, understands the pain of a leader who has failed us. We want to believe the best, but have often experienced the worst. We have been abused, let down, trampled, silenced, thrown beneath the wheels of the charging bus. Belonging has been revoked. And perhaps faith, too, has evaporated along with the communities we once committed ourselves to.

But disillusionment is not unique to American Evangelicalism. Just look at Americans’ responses to their government right now.

Once, we Americans may have been naive enough to tell ourselves that we believed in democracy. We were the definition of democracy. We may have believed that our nation had reached the pinnacle of human innovation, that we were the best, the most just incorporation of humans on the globe, the most exceptional of exceptions.

And we may have believed that our politicians were basically benevolent. Even if their personal lives were… embarrassing, still, we believed that they worked toward “the common good.” They generally tried to do what was right.

In other words, we may have believed our own propaganda about our national identity and our leaders.

Of course, Black and Brown Americans, immigrants, and the lowest working classes understood the lie of democracy and the underside of our government better than White Middle-class Americans like myself. But to speak to those folks for a sec—I suspect that even if “ACAB” had become your anthem, perhaps you still had hope that your vote mattered? Or you hoped that a legislator or judge could hold a bad actor accountable? Or you hoped that if the right politician were elected, then the aims of MLK, Jr. might finally be accomplished nationally?

I suppose I can only speak for myself. I believed in these things. I understood some individual leaders as evil or misguided, but I still hoped for a long-haul lean in the direction of justice and mercy within my nation’s system of governance.

I don’t believe that to be true anymore. Today, I see the most powerful actors in our state as “empire,” a force for evil and exploitation rather than a force for protection and common good. And I do not know if we’ll come back from the harm of this administration. If we do come back, which I very much hope we do, I do not believe we’ll be the same.

(I know this is bleak, but I pledge to always be honest with you here. If you’d like to hear more of my sunny optimism about the government, tell me in the comments.)

So then, I want to ask you, if our leaders do fail, if disillusionment arrives in force, how should we respond to it?

When those we believed to be valiant, righteous, or messengers of God prove their inhumanity or immorality, do we defend them? Do we believe it’s our job to discredit their accusers to prove our loyalty to a leader who doesn’t know our name? Do we trust our own discernment and the discernment of those involved? When our institutions prove corrupt, do we hold on tighter or do we seek to build something new?

I don’t believe there is one right answer to these questions, though I’d encourage you to consider your motivations for defending a leader before you do it.

One of the reasons I wrote a book about Genesis was to encourage spiritual autonomy, starting with how we read the Bible. Trusting our own spiritual gut and the Spirit of God means retaining a sense of autonomy over how you engage with your faith. This is one of my soap boxes. (And I believe it applies equally within any institutional space, by the way.)

In unhealthy or abusive church communities, one of the first demands from leaders to their congregants is that congregants should abdicate their reason, feeling, and responsibility for themselves. Christian leaders will ask their followers to give up their discernment. They’ll say, don’t trust your own mind and gut, trust theirs instead.

But faith communities—and governments—do not have to look like this.

What if Christians developed cultures of growing, thinking, deep feeling humans, where leaders sought to privilege each view and voice and where followers learned to trust the voice of God within them? What if your instincts were treasured, if you were treasured as a messenger of the Divine, image bearer of God? What if your spiritual autonomy was nurtured, encouraged, and trusted?

What if your voice, your diverse identity, your vote truly mattered to democracy? What if your presence in your community really could change the lives of those who interacted with you? (It already does. Authoritarianism can’t take that local communal relational power from us.)

When we learn disillusioning information about our heroes—like Elisabeth Elliot and Dr. James Dobson—I hope we will respond with openness because it is an opportunity to grow.

It may also require us to practice the most essential of Christian disciplines: we can change. Some people call it repentance, but in this moment, when changing our minds, theologies, and political parties is demonized and suspect, I think “change” captures the sentiment better. And we can always about-face, walk in the opposite direction, and make amends with those we have harmed.

Or we can choose to dig in.

But let the reader understand: however you respond reveals more about your own character than about the person you choose to defend.

Listen, learn, and change ad nauseum, for this is the path of Jesus.

Thanks for reading.

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

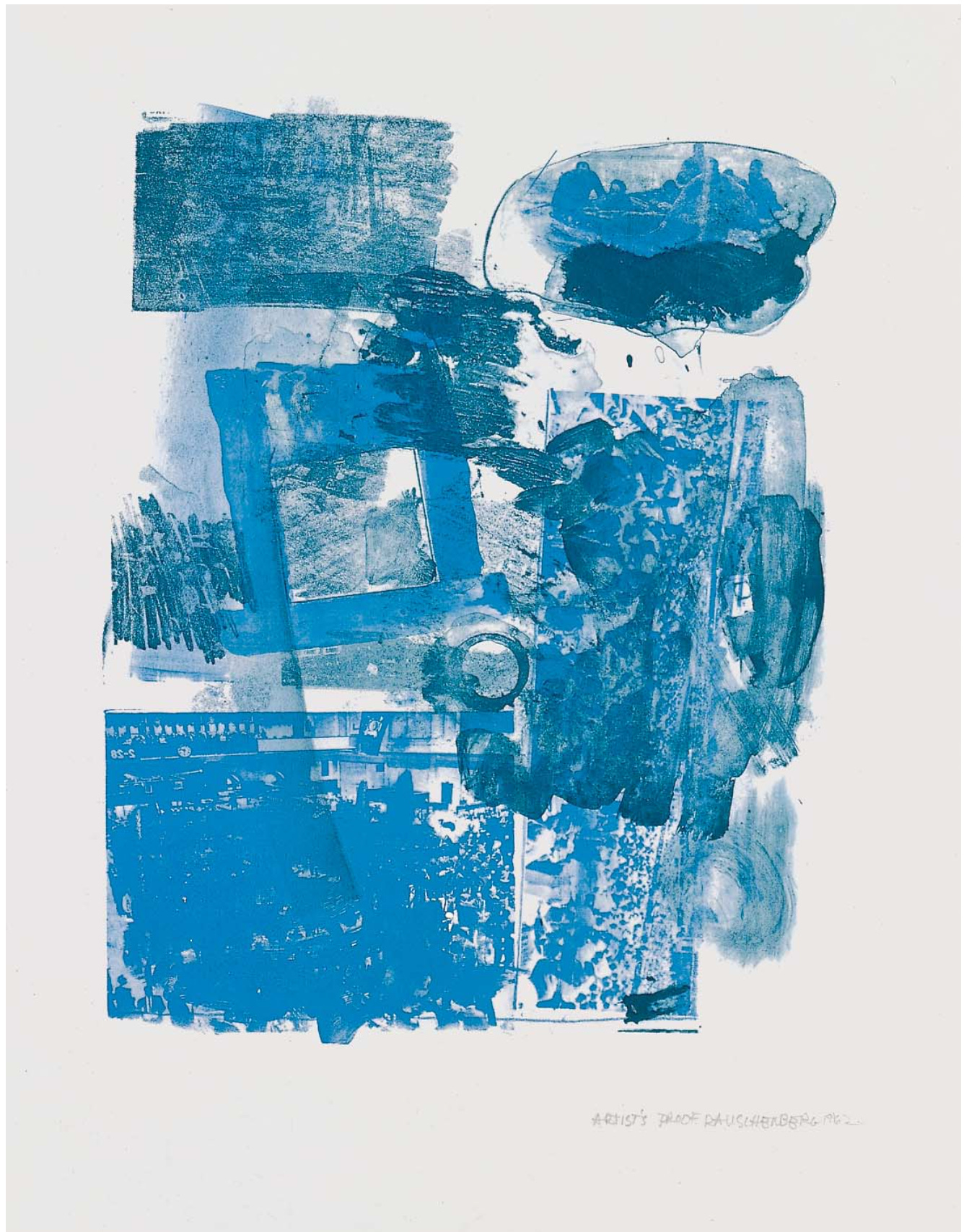

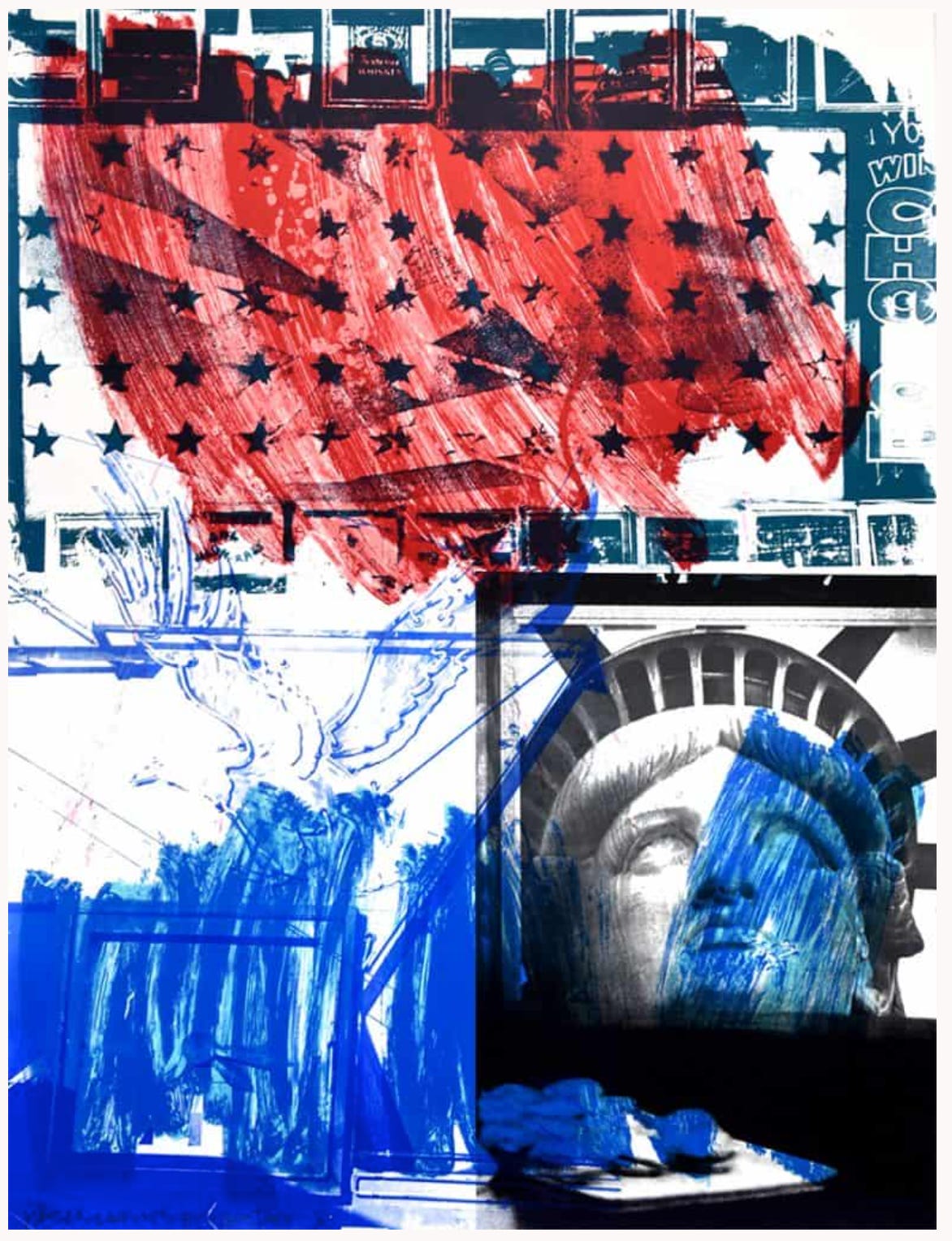

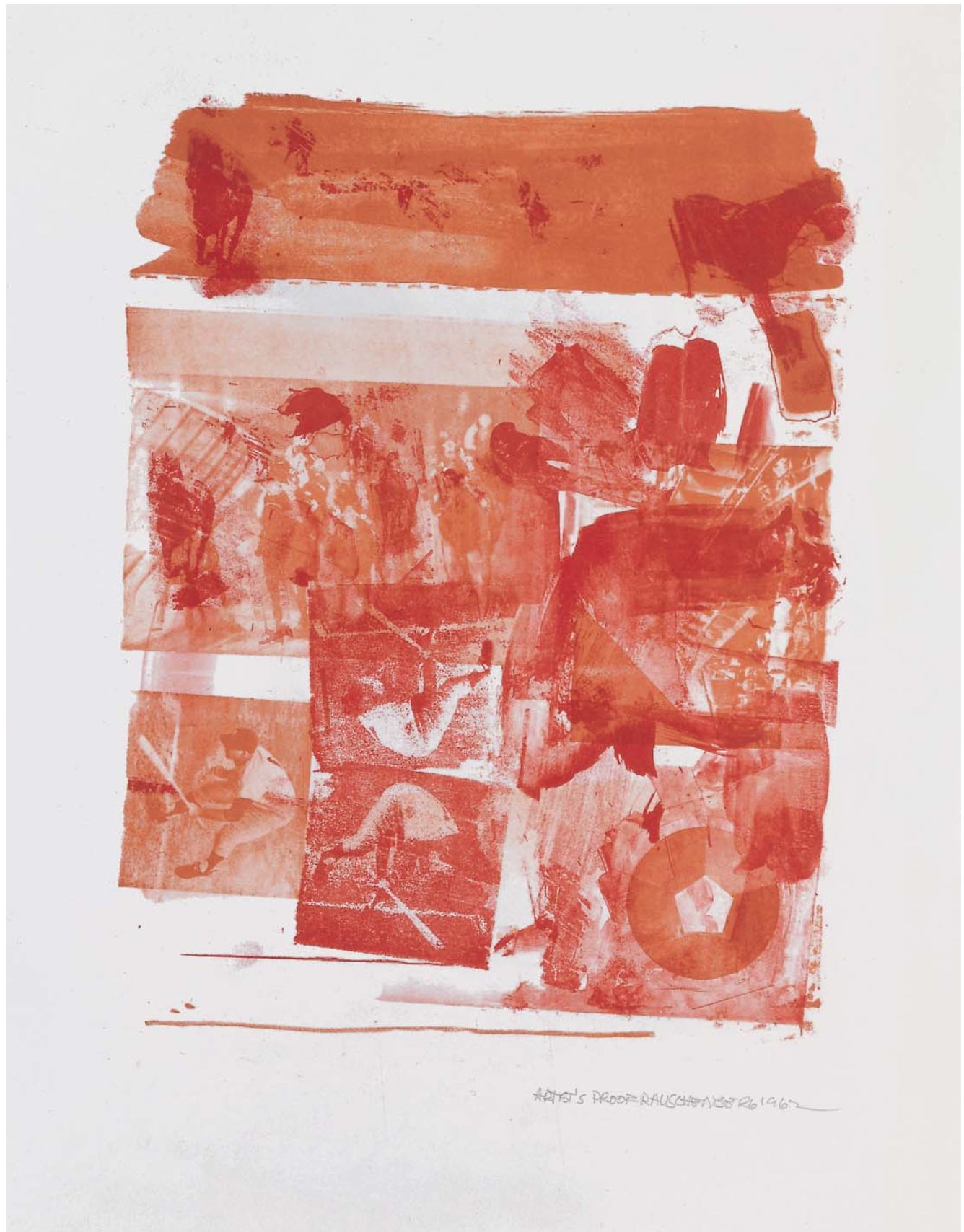

Just for Fun…

My 10-y-o son laughed so hard at this video that his tummy hurt. You’ve been warned.

OK that clip at the end was a welcome reprieve from all the garbage of this year. Thank you. On a serious note, thanks also for the article. I guess shooting the messenger is still alive and well. :/

Yes to spiritual autonomy, and to embracing change! Appreciate your writing as always!