the Empathy List #153: Focus on Your Own Damn Family

On the legacy of James Dobson, the "spanking" psychologist.

Hi friends, Liz here.

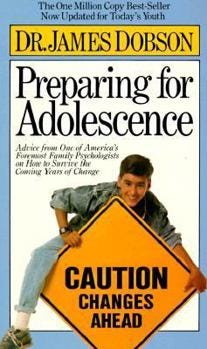

Welp, I have a hunch that you’ve heard the news: the evangelical pop psychologist, Dr. James Dobson had passed away, the man who founded Focus on the Family and aimed his significant influence toward preventing marriage equality in America (or at least in Colorado Springs, Colorado.This is also the man who endorsed our current president in 2016 because he and Don had talked for a few minutes, so Dobson could assure his followers that Don was now a “baby Christian”.

And this is also the man who gave me the sex talk (and probably many of you, too).

I have written about JD in the past here—

However, today, I want to focus on something more personal—I want to talk about spanking, because spanking is how many of us learned that we were bad to the core.

But first, a confession:

I spanked my daughter once.

She’s my firstborn, and she was two, maybe three years old. She had grown overstimulated, and she was crying, yelling, hitting, kicking. I do not remember the circumstances as clearly as I remember our bodies—me, sitting on the wooden floor of her room, my back leaning against her door, her body, thrashing in my grip. In those days, I often had to duck her elbows when she was mad, but I had determined me move closer to her, not further, when she was angry or sad or confused. I would sit with her in her room, on the floor, blocking the door, while she raged, and often, I had held her to keep her from hurting herself or me in her rage.

I do not know how it started or what led me to do it, precisely, but I remember that my anger felt hot as I placed her, belly down, onto my thigh and smacked her bottom with my palm. The first time wasn’t sharp enough, I decided, since she hardly responded, so I repeated the gesture. She burst into tears. And right then, I knew that I had hit my daughter to assuage my own anger, to stop her own feelings intruding upon my own, and I hated myself for it.

I apologized to my daughter immediately and held her in my arms until she calmed and resumed her play. Then I called my husband Jeremy, and together, we decided that my own rampant anxiety, so high during this period of my daughter’s life, meant that I struggled to metabolize her emotions with the calm of a grown-up. I knew the kind of mother I wanted to be—calm, unflappable, and present. Yet I found myself wanting to rage at her, or even to smother her feelings in her mouth (metaphorically only). Jeremy helped me acknowledge that my fear of our daughter’s anger and sadness had little to do with her—that was my problem.

So, I returned to therapy for the third (?) time, to settle the interior question that my toddler’s emotions had raised within me: why did my daughter’s negative emotions make me so afraid?

Dobson is famous for his teaching on spanking kids. In an earlier draft of this post, I spent quite a few paragraphs quoting his words and realized, neither you nor I want to read them.

Instead, I’ll give you the gist: In Dobson’s own words in Dare to Discipline (EW WHAT A TERRIBLE TITLE), spanking is “the shortest and most effective route to an attitude adjustment.” The kid can have their big feelings, sure, can even disagree with a parent, but when it comes to action, a kid must comply to the caregiver’s whims. Because that is the order of the universe. Parents over kids, husband over wife, God over all: the umbrella of evangelicalism’s traditional gender roles.

And, preferably, that kid to parent obedience should happen quickly and efficiently in a way that won’t embarrass the grown-up. And spanking becomes the way a parent makes the family automatons.

Okay, I’ve already admitted that I do not spank my children. The pediatric research discredits the “effectiveness” of corporal punishment, even in the best-case scenario, and I myself have experienced the complexity of administering such a punishment from the side of the parent and child. (I was spanked by my parents, as were most of us raised within white American evangelicalism of the 90s and 00s.)

But my primary disagreement with Dobson centers on autonomy.

Dobson describes spanking as a way to teach a kid about a social “danger,” and lists the dangers as “defiance, sassiness, selfishness, temper tantrums, behavior that puts his life in danger, etc.”

What does Dobson mean, precisely, by “sassiness”? The danger appears to be within the tiny human, originating with his will and emotions. The danger is original sin.

Or perhaps the danger is the parent: when a child dissents or expresses any other version of will, intent, autonomy, the danger is that the parent will hurt her for it.

Confusingly, Dobson’s definitions deepens when set beside another nugget of advice, in which Dobson encourages parents to let their kids express dissent respectfully: “The child should be free to say anything to his parent, including ‘I don’t like you’ or ‘You weren’t fair to me, Mommy.’ …[though] the parents should prohibit the child from resorting to name-calling and open rebellion… and Dad should be big enough to apologize to the child if he feels he was wrong. …It is possible to communicate without sacrificing parental respect…”

So then, what’s the difference between “respectful dissent” and “sassiness”? What counts as reasonable and respectful disagreement? When can a child put their foot down and be heeded as an autonomous being? And how do we teach a kid to say “no” to other types of abuse when she learns that those who love her can use or hurt her body, without her consent and supposedly “for her own good”?

Dobson’s book The Strongwilled Child demonstrates his real failure as a teacher: rather than acknowledging the preciousness of diversity within humans, those he deemed the “strongwilled” as flawed. In order to fit the nonnormative into their parents’ (or white american suburban evangelicalism’s culture?) expectations, the spirits of these chidlren had to be broken.

This is not so different than the philosophy of the American prison system, as Howard Zinn writes in his prescient book, A People’s History of America: "The approach was summed up by the warden at Ossining, New York, penitentiary: ‘In order to reform a criminal, you must first break his spirit.’”

When I read those words, I thought of Dobson. What is the solution to taming the wild child? Break her. In fact, the metaphor Dobson uses in The Strongwilled Child is that of domesticating a dog and claiming mastery over his animal. Fundamentally, Dobson’s work seems to take issue with relational conflict between parents and their children, and the way to fix that conflict is to physically domineer over the smaller and weaker party.

So, ultimately, my issue with Dobson is not spanking, but authoritarianism within parenting. The long slow slog that is relational, gentle, or respectful parenting (whatever you call it) means that I MUST treat my nearest neighbor as myself. That doesn’t mean a parent can’t lead a child, that a parent can’t set boundaries. But it does require respecting my child as a whole person, a person made in God’s own image.

Personally, I never felt that level of respect or trust from my parents or other adults when I was a kid and teenager growing up within white American evangelicalism.

Tell me: how are you thinking about the deaths of men like Dobson, McArthur, or other giants of white American evangelicalism?

Within my family now, my husband and I aim to teach our kids bodily autonomy. We have learned to expect a certain level of relational chaos in our home because we want to encourage our kids’ expression because we have seen it result in independence, autonomy, and self-awareness that can allow our kids to become healthy adults. That’s a trade that, to me, is worth it, even if it means that we have to leave dinner at a restaurant early to resolve a disagreement. My own convenience is worth less than my child’s dignity.1

Which leads to the last point: one overlooked element of Dobson’s legacy is family estrangement. Focus on the Family admits as much, and they now offer paid courses and teachings for parents whose children won’t talk to them.

(See Krispin Mayfield’s work on estrangement in authoritarian family systems here, including discussion of the courses offered by FotF, sheesh.)

I believe is as an admission of failure. The methods Dobson believed would work—to make kids into copies of their Christian parents—simply don’t. And in Dobson’s wake, we see broken families. I myself am one of these estranged daughters, and I can tell you that estrangement breaks the hearts of those on both sides, whether parent or child, whether the boundary-setter or receiver.

As we weigh the legacies of men like James Dobson, I pray that we would remain tender, that we would seek out the nuance and complexity in the stories of others, and that we would uphold the dignity of the vulnerable.

We can honor those he dishonored.

In the end, I believe that’s the most beautiful corrective to Dobson’s teachings that we can offer to each other.

Thanks for reading, my friends.

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

Psst, for a wider lens on how the wider exvangelical community views Dobson, I’d point you to Kristin Du Mez’s excellent run-down:

Or to D.L. Mayfield’s summary of Dobson’s action and influence during his lifetime:

Despite my many disagreements with Dobson, I have to admit that I was never especially bothered by the spankings my parents administered to me as a kid—I was a normative, co-dependent, goodie two shoes, a first born girl, and the shiny apple of my parents’ eyes. So, of course, my parents’ “discipline” approach, while influenced by books like Dare to Discipline, never looked extreme. (Believe me when I say my family had other problems, which is likely why spanking did not register for me.)

Yet others did (and do!) experience Dobson’s work as abusive. When considering Dobson’s work, adopting a posture of empathy means we make space for those—like the abused kids Dobson acknowledges himself—who will experience spanking as abusive. Many see Dobson’s teaching of spanking as de facto abusive, and I believe them when they say that in their experiences, his teaching led to abuse.

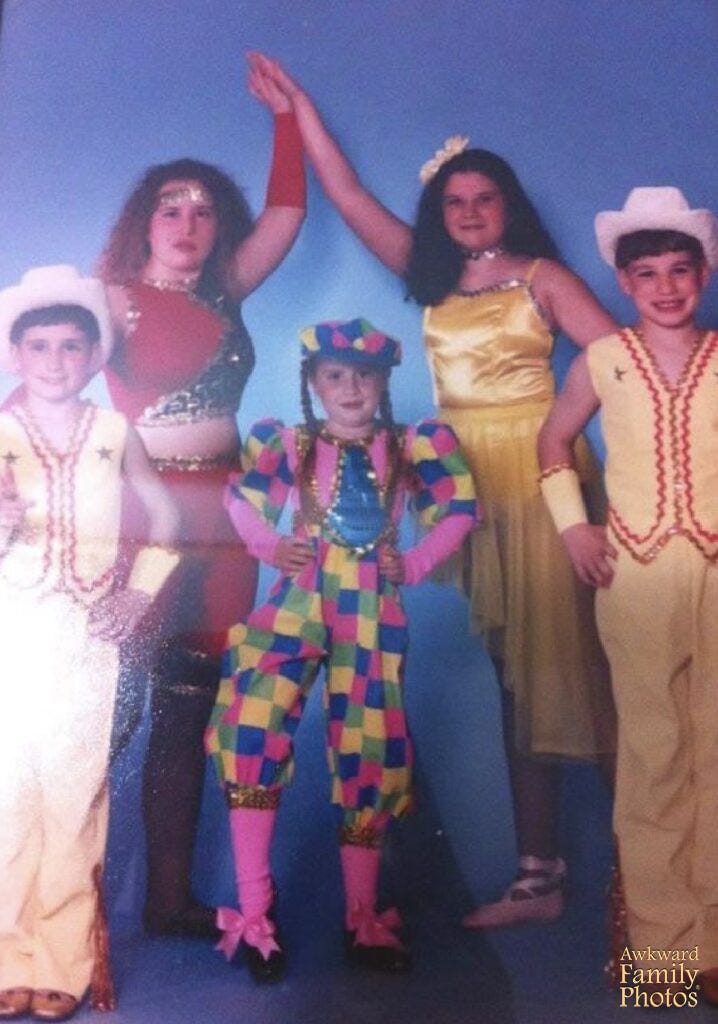

This especially true for those who did not fit into normative cultures, such as those who were neurodivergent, LGBTQ, or simply extra energetic. These kids tended to be targeted by such teachings, and their parents used Dobson’s methods to try to spank them “normal.” It didn’t work.

I’m so deeply grieved for those of you who experienced this, and I hope you now receive the love and grace you need to repair.