the Empathy List #147: Set it Free

Release the art that's become dear to you so that it can become dear to someone else.

Hello friend, Liz here.

Today we’re talking about the end of the artistic process. That is, after nurturing our inner muse, sitting down to complete the hard work of creating, and revising the original to shreds, we must then release our artwork into the wide world. And that may be the hardest part.

The 4th episode of Knock at the Sky: A Creative Journey is live, and you can listen in your podcast app of choice.

So far, in this series, we have talked about idea, craft, and revision, and today we're talking about release.

When the final draft enters the big wide world, how do you accept that your job as the artist is finished, and how do you receive the reception of a wider audience? How do you interact with that audience, and what happens when viewers and readers make the art their own, reading meanings into the work that you never put there? And what does the Bible have to do with any of this? (A lot, apparently.)

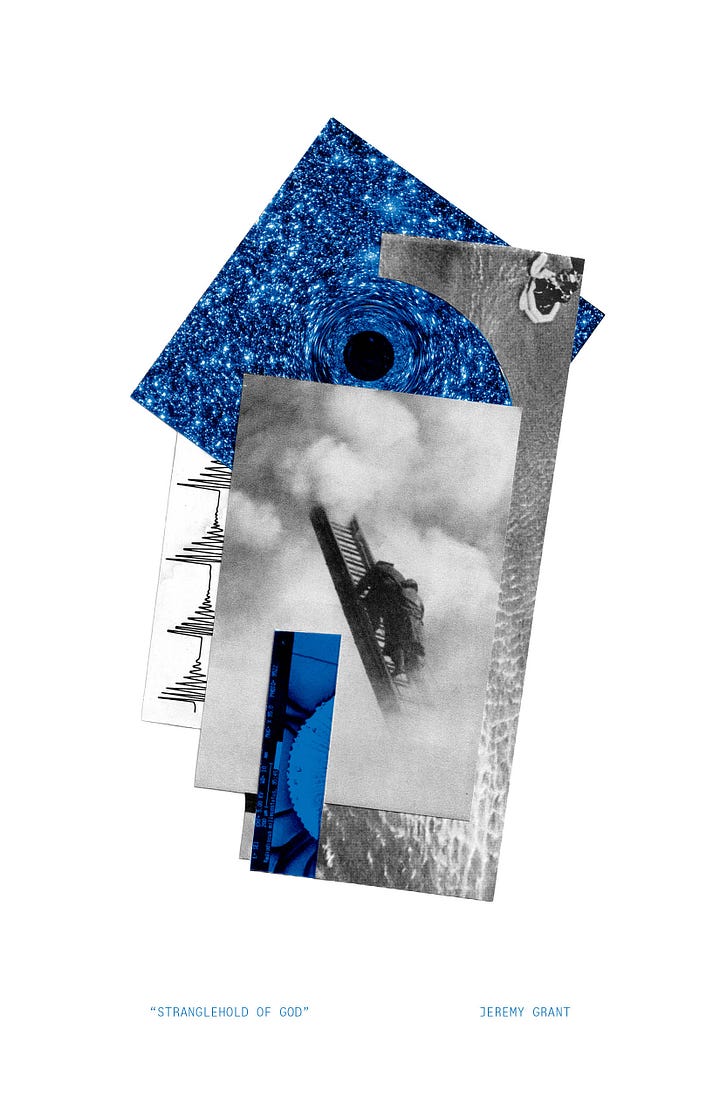

We also discuss the fine art collages that precede Chapters 10 and 11 in the book that has inspired this podcast.

Subscribe and/or listen here—

Apple Podcasts / iHeart Radio / Spotify / Amazon Music and Audible / Stitcher

Below you’ll find an edited transcript of our conversation.

Thanks for reading and/or listening, my friends!

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

And now, I’d love to hear from you: how has reading Knock at the Sky or listening to the podcast inspired you to create for yourself? What art are you working on right now? Tell me in the comments!

THE PODCAST— Episode 4: Release

Knock at the Sky: A Creative Journey

What’s better than perfect? Done.

JEREMY: So in previous episodes, we have started with some of the common questions, you know, where do you get your ideas from? Those sorts of [questions]. I think in this case, the common question is, how do you know when something's done? Because I think a lot of artists, you could continue tinkering and changing and revising your work ‘til the proverbial cows come home.

LIZ: I am a hundred percent that artist. I am that artist.

JEREMY: You told me a story like authors who at the readings of their book are still editing and rewriting in the margins of their copy.

LIZ: Oh, this is common, actually. They'll be holding their published work in their hands to go to reading, to read the published work to an audience, and they will still have a pencil in hand and be correcting text on the page.

JEREMY: “I wish I would’ve done it this way…” [Laughs]

LIZ: Yeah, I mean, I feel that way for sure. [But] there is a reality where you… say it's “good enough.” You might run into a deadline, and then there's just no getting around it. You're just stuck. You have to turn it in. You're on the hook.

JEREMY: A lot of times artists need deadlines. You keep creating until the buzzer, and that infuses the white hot terror of “needing to get [it] done” ahead of the deadline.

LIZ: See, I'm an over performer, so I turned in my manuscript early for this book, but then kept revising long past the time when I was allowed to keep revising. [Laughs] So my sweet editorial team, I'm so sorry, but it's very hard to stop. It's very hard to stop—for me. The way I made peace with this [book] as it is was saying, I really did do the best I could. I literally read the words out loud to myself. There were things I had to do to feel good [like,] I've done what I can do, and now I'm just gonna release it. And it's not gonna be perfect. It just will not.

JEREMY: Once you've done the work up front of setting your goals—defining your idea, going through the practice of actually creating the work, making the draft, then revising and editing—once you've gone through all those steps, at a certain point, you just have to call it done. …There's the famous phrase: the good is the enemy of the great, and good enough is the enemy of whatever, perfection, or [something]…I forget how this saying goes. There are lots of those like aphorisms [saying,] if you call it too early, then you won't ever achieve excellence.

LIZ: Have they ever met an artist? [That’s torture for an artist.]

JEREMY: The flip side of that, [an idea] I've heard often on the design side of my practice is, you know what's better than perfect? Done.

There's a well-known designer, James Victore, that talks about that idea a lot. What's better than perfect is done. If you can't turn in the manuscript at the deadline, you got nothing. If you can't show up at the gallery with your paintings framed and ready to hang on the wall, they're not gonna show, you won't have anything in the end.

So there is a point where it's “pencils down, you're done.” If you have a reasonable timeline with a creative project, hopefully you can wrap sooner than the deadline, and hopefully give yourself a chance to sit with the work and be able to, at a minimum, enjoy the fruits of your labor before it goes out in the world.

And maybe this is a Genesis parallel: God creates, and then God steps back and says, “It's good.”

LIZ: If only [God] had said, “It's good enough,” you know what I mean? Then we would really have permission [to not be perfect].

JEREMY: I love that. Yeah, the idea of just enjoying it for a little bit before it goes out and takes on its own life.

Gluing Down the Paper, Setting Down the Pencil

LIZ: I wanna ask you, for your work, when do you finally glue it down? I mean, I know you use the double-sided tape and you… kind of go back and forth…

JEREMY: Yeah, we talked about it in the last episode my incredibly rigorous method of using little ticky tacky pieces of tape to tape my papers together.

LIZ: Is that what it’s called? [“Ticky tacky tape”?]

JEREMY: No, I take regular scotch tape and then I stick it on my shirt to get some lint on it, so it's not too sticky.

LIZ: Very high-tech process in the Grant household.

JEREMY: Here's the deal, proprietary art processes and gatekeeping around art process is stupid. All artists just do whatever they feel like in their studio. So, here’s what I do: I take a little piece of scotch tape and I stick it to my shirt so it's not too sticky and it doesn't rip the paper. Then I gently stick things together and allow them to sit as a composition for a while. And I come back to it and I look at it fresh [later].

So I'll make a collage, it's done, I feel proud of it, I feel good with it. I'll go away for a day or two, I'll come back to it and look at it with fresh eyes. Sometimes look at it upside down or in a mirror… just [to get] different views on it. And then if it still… needs something or I'm not totally happy with it, I'll rework it and then do the same thing over. If I come back to it after a few days and I'm like, it's good. It doesn't need anything. Then I glue it down.

LIZ: You just go for it. And I have a [follow-up] question, if your shirt is new and doesn't have a lot of lint on it, do you put the tape on the couch to get it nice and linty?

JEREMY: Uh, yeah, yeah. [Laughs]

LIZ: Well, now that we’ve got that settled… I can tell you that I relate to that [reasoning]. …You were talking about a point where you just decide.

JEREMY: So there's these two aspects of it: one is like you decide on your own, [this artwork] is done. Maybe that coincides with a deadline, maybe it's ahead of that, and you have that reflective moment [where you’re certain,] it doesn't really need anything else. Let's glue the collage down, let's apply the varnish to the painting. Let's frame the work or label the manuscript—”final FINAL version 4 truly the final one.”

LIZ: I have about five of those [for this book].

JEREMY: And you put it in a separate folder, or you back it up to your external hard driver or whatever your process is to indicate something's done. So that's part of the equation.

“My Six-Year-Old Could’ve Made That”

JEREMY: [After you decide a work is done,] the other part is… mentally preparing for [your art] to go out in the world and have its own life. We talked a little bit in the last episode about creating with an audience in mind, not solely for yourself. [When] …I'm creating art [at first,] I'm the only arbiter of what's good. But then there's an editorial process where you decide, does this actually mean something to someone else? Does this move someone else? Does this do anything for them? And that's a consideration [at] this stage.

LIZ: This is the moment when you have the broadest audience engagement. So you start thinking, not just [about the] feedback from a few trusted voices. Now you get everything, especially in the age of the internet, right? If anybody reads it or sees it in the first place.

JEREMY: Yeah, “I don’t get it,” “it sucks,” “my six-year-old could have made this,” comments on your appearance…

LIZ: Yeah, “you’re ugly.” I get the weirdest comments, oh my gosh.

JEREMY: People are… argh, I’ve got words for them.

LIZ: They’re just trolls. They’re just trolls. It’s okay. I feel bad for them. I, I think they have sad lives, and I have a really happy life.

JEREMY: If you have actual genuine comments on the work, artists typically love that. It doesn't have to be all good comments, but like real feedback—”I didn't understand this, but I was moved by this other part”? Amazing. Great. It’s such an honor to have someone engage with your work for more than a few seconds on Instagram.

LIZ: Yeah, any earnest engagement is so welcome.

JEREMY: …but as an artist, you have to mentally prepare for putting [your art] into the world.

Waiting for Reviews Be Like…

LIZ: So at this point when we're recording this, I don't have any reviews back on the book.

JEREMY: It’s done.

LIZ: It’s a complete book.

JEREMY: Out of our hands.

LIZ: But I have not read reviews in all the important places that may or may not review it. You know, they may deem it totally not important enough to review.

JEREMY: We may get crickets. We may get silence. We may get negative reviews.

LIZ: Right, we could get terrible reviews, who knows? You know, the Gospel Coalition could give me negative one stars. And actually that would be great for book sales. So I'm okay with that. A friend told me that if TGC reviews it, then I've made it, because then they can't ignore me. So I'm fine with that. If you guys wanna reach out…

JEREMY: If you’re enough of a heretic, then you will show up on these peoples’ radars. [Laughs]

LIZ: I’m working on it, I’m really working on it. What's interesting about this phase is, it does require a level of inner fortitude. You need some boundaries emotionally and probably even physically to protect yourself, you know, to say there is a level of criticism that's okay, whatever, I'm fine with. There is a level that I won't even engage with at all. I may not read Amazon reviews. I haven't yet drawn my own physical boundaries around this. But I will say, my internal boundaries are very strong.

And in that regard, the people's voices who matter the most to me are the people who actually know me in real life. You know, those are the people with whom I have real relationships.

And[, by the way,] I do not mean whether these [IRL relations] liked [the book]. That's [a separate] ... question. And I have had to learn boundaries around [whether those close to me like my work especially]… with family members. There's some things we discuss with [our] families, …and my art [is] not in the discuss category, and that's okay. That is actually okay with me.

What matters are those trusted close friends. They can read my work and tell me, am I being generous [in my book,] even to the people I disagree with? Am I being curious? Am I making space? Am I creating a safe place to ask questions? You know, those are the things I care the most about. And the people who are able to judge those things and really tell me the truth about that are the people close to me. Their opinion matters more to me than any troll online.

JEREMY: As it should. Absolutely. And these are people that have different disciplines from you. Some people have spoken into this work who were writers, and you valued their opinion on your craft. We already mentioned previously [receiving] a theology edit and a science edit and other [editorial] checkpoints …where you intentionally sought out feedback from people who might have a different opinion than you, but …have a perspective that you valued in the process.

Does making art matter if you’re never “discovered”? (Yes!!!!!)

JEREMY: So you mentioned …internal boundaries, and something I've thought about a lot is internal versus external validation. Is making art inherently valuable if no one ever sees it? Or if your work is never discovered? We talked earlier about Vincent Van Gogh and his solitary, lonely, depressed life where he didn't sell [anything]. I think he sold one painting in his lifetime. Was it worthwhile for that artist to plug away in solitude, painting out of passion? Was that worth it? Was that good?

LIZ: And was it only worth it because we later decided it was good [artwork]? Or is it inherently worthy? Is the practice of creating worthy?

JEREMY: In the Denver area, we have the hometown hero of the modernist painter, Clifford Still, who was famously fickle about who he would even allow to purchase or display his work. He was… so internally validated. He [believed so strongly in] the value of creating this work that he actually would often paint duplicates if he was going to sell [a painting].

LIZ: That's some white man privilege right there. That's all I gotta say.

JEREMY: True, true. [Laughs] He was not depending on the arts sales to pay the bills.

LIZ: It was “old money,” let’s say.

JEREMY: [So] Vincent Van Gogh did [his work] in poverty. Clifford Still did [the same] while still making a life, you know? [That’s]… internal validation. You… have to have some conviction around your own work, that [what I’m doing] is worth doing. And in the times where you've gotten frustrated with your writing career… [Liz,] you alluded to the fact that you've written multiple books before this one …, and there have been times where you feel like giving up, times when you feel like it's not worth [continuing to write]. Nobody wants to pay me [to write]. Like, we're not really making a lot of money on this project…

LIZ: This one currently?

JEREMY: This one, yeah, even the one that gets published. We’re not making a living off of it. And [we’ve had to develop a]… shared a vision […around] a lifestyle of making art. [We’ve had to decide] that creating art is a practice that is inherently valuable because it's more about a posture than it is about a product.

LIZ: It forms you.

JEREMY: Yes. It's formative personally, and with other people, and in communities of artists, [and in] the broader community, you form these connections. …This way of living is observant, values beauty, values aesthetics, empathy, curiosity. And there's a storytelling aspect. And for you, [rediscovering purpose in art making happened]… by reconnecting with other experiences … that had been de-centered in our culture, and saying, an interpretive act shouldn't be siloed into one culture. That also ties into this idea of audience, interpretation, and how your work becomes [universal]…

Once your art becomes public, the work is no longer yours; it’s ours.

LIZ: So once your work is released beyond sort of your trusted circles, whatever that is—whether you post [your writing] on a blog, or you show it in a gallery, or you upload it to Spotify. All of a sudden, you're now public. Your work is no longer private. It's no longer only yours. And so people are encountering this work without you there to explain it…

JEREMY: …until you make the podcast

LIZ: Right, until you make the podcast to explain every little bit, so you could be in control. I don't know anyone who would do that. That's weird. It seems stupid. Really self-absorbed.

JEREMY: But it takes on a life of its own. And people get to have their own experience of it.

LIZ: [Your audience gets to] have their own experience, they have their own emotional connection to [your art], you hope. They interpret things in it that you didn't know were there, or you didn't mean to put that there, but somehow they took this thing out of it.

JEREMY: Your art… can become a part of someone else's identity. Which is daunting. For example, people identify with something in your work and they say, this reminds me of me. …I had someone come up to me at an art show and say, this figure, this lonely figure in this piece of art you made, that's me. And… proceeded to tell me about how they had just gone through a divorce and this whole life story. And it was like, oh, wow, this person really made a connection and is processing their life experience through this artwork.

For a work of literature, people have their favorite books, they have their least favorite books. Sometimes both of those become sort of self-expressive.

LIZ: [What you love and hate is] equally valuable in defining.

JEREMY: It's like, I love this, and I'm against this. I hate this art. I had a terrible experience at this movie. And those kind of reactions then place an artist’s work in a new context of self-identifying talismans for people.

LIZ: Yeah, it is kind of strange [how art can] become symbolic [identifiers]. I mean, the fact is[, as the artist, this artwork] is not yours anymore. And releasing that ownership is a challenge, …especially in a culture that wants authors to be brands, you know? But it's important for us as artists to accept this broader influence and to accept it with open arms. [Our role becomes] just offering [our work] as a gift. And maybe I don't have every key to interpretation of this [work I’ve made].

An aside about the Jewish mystic heretics, the Kabbalists, and a legend of a 600,000 piece puzzle…

LIZ: You know, there's this legend among these heretic Jewish mystics, the Kabbalists: …there were 600,000 Jews at Mount Sinai when God gave Torah to Moses.

JEREMY: The classic tablets…

LIZ: The ten commandments. You know, the mountain is on fire, …and there's smoke and lightning and God is speaking. And so they tell the story like, there were 600,000 Jews [present at the mountain] on the day that God gave the 10 Commandments, the whole Torah, to Moses. And each of those 600,000 people received one 600,000th of the Torah. So they each got this tiny puzzle piece of Torah. And in order to understand it as a whole, all of them needed to contribute their puzzle piece, their voice, their understanding and interpretation of Torah.

JEREMY: That story… has a lot of things to teach us about how we engage with ancient manuscripts like the Hebrew and Christian scriptures

LIZ: …which I happen to care about a lot, obviously.

JEREMY: That’s what the book is about. [Laughs]

I think that's fascinating, too. … We’ve really narrowed our interpretive framework for the Scriptures in the United States, in the West, in sort of these white evangelical spaces. The interpretation of scripture is very narrow, but historically, this manuscript has lived in cultures across the globe, had very different expressions and interpretations and translations. And one myopic view shouldn't dominate the conversation. [But] that actually takes some intentional de-centering of our own worldviews and perspectives. We're not the center of the universe here. My viewpoint shouldn't be the center of all things. Instead, I should actively seek out the 600,000 different ways to read [and interpret]. Does that resonate with you and how you were thinking about creating this work?

LIZ: Absolutely. …My hope would be even that …this book, Knock at the Sky, …births other versions. …whether that inspires ekphrastic work in response, whether that inspires people to read the Scriptures with their own midrashic lens, whether that brings people back to some of these interpretations that have been considered marginal [by white theologians]...

I think it's really important as artists to [practice] releas[ing] what we [have made].

You know, I'm not the final word on God, I'm not the final word on the Bible. I'm not even the final word on my work of art. There is a sense in which I started it, I got the ball rolling, but I don't expect that [to be] the end. And my, and in fact my hope is that it isn't. [Good artwork should inspire better artwork that comes after it.]

JEREMY: You've embarked on this work as a series of questions. [You’ve] elevat[ed] the questions over the answers, [taken] these deep dives into rabbit trails, and then pull[ed] the original sources back [into the mix], collaging them together, allowing them to juxtapose... in interesting ways that raise more questions and create a sense of spaciousness around the experience of this ancient manuscript. And it sounds like you hope that [play and art making] continues for [your readers]. Like, this isn’t another box that people lad in, but it’s a launching pad for more thought.

LIZ: Exactly. In fact, I think that's a good way for artists to deal with releasing their work. [We can] say, I'm putting this out into the public eye in order to start conversation.

And when I think about the scriptures, what I'm trying to do is [emphasize that] the most important thing …is the conversation. It is… the ongoing wrestling and conversing with each other to try to figure out what this book means, what this God is, how we're supposed to relate to [whatever lies beyond]. I think [the religious life] is meant to [evoke] more questions than answers, and I think that's a better way to live as humans and as Christians.

“I am not the final word on my own work.”

JEREMY: I loved what you said about, you're not even the final word on your own work. [It makes me think of] being open to the feedback that comes, and being open to whatever [that feedback] develops in you.

You and I have talked multiple times about my ideal sermon, … which would… start with the redactions from last week's sermon. [I wanted a pastor to say,] “Okay, last week this is what I taught you, and I got a lot of feedback from you [all], and maybe I changed my mind [about] something [I taught]. I've never heard a religious authority figure redact anything.

LIZ: Maybe this is a good time to say our next podcast episode will be entirely redactions.

JEREMY: [Laughs] Yeah, please. Maybe we should, if this [podcast] continues… Leave us comments.

LIZ: Yeah, tell me how I was wrong. I wanna hear from you.

JEREMY: Nicely please.

LIZ: Jeremy will read them first.

JEREMY: But yeah, …give us feedback.

… this is a moment [in time], and this is a work of art that's being produced in this context. [But] it will become something else over time if it persists, if it's resonant, if it gets traction. (If anybody listens to the podcast, then they might give us feedback.) But if people engage with [artworks] over time, they will become the final word on what that work of art [meant].

Even God makes space for human interpretation of the creative work that represents Her.

JEREMY: There's an interesting parallel too to with [the Bible.] In the last episode [we talked] about Sodom and like, why did God intervene to throw down justice on this wicked city, but [why did God] not intervene on the behalf of vulnerable people at other times? And that's …the big question, but… we… skip over that in the handling of the scriptures. [We assume that the] scriptures were… handed down like the 2001 Space Odyssey, monolith… [Liz interrupts to sing the 2001 Space Odyssey song.] That’s the one.

We think of scriptures as being… handed down from on high in this pristine method, like they're immaculate. And then I forget if I've actually been taught this, or if this is something I've imbibed by being around these spaces, but the idea that God has divinely intervened in the course of history to protect the scriptures, and [even] certain translations of the scriptures, so that we [today] have this perfect immaculate version of the Bible in English, preferably in the King James version, or you know, whatever your brand of choice.

And when you actually look into [Christian] history—which is horrible—there are so many things along the way where you realize, there was an evolution of the scriptures. The King James version was commissioned by a tyrant and a murderer. He was a horrible person. Like every king was. And so… you get into the idea of a female perspective included in translation things… and why was it [translated that way?] It’s just patriarchy.

It's a reinforcement of a cultural ideal that men should be in charge. …And … there are so many things like this along the way through the scriptures. Personally, I don't think that takes away from the Bible’s value, but I think it shows God's willingness to, as an artist, release this work into the world. [And] … those times when we see non-intervention from God and we're cursing the sky, … sometimes the only answer in that [God is] allowing you to be free.

LIZ: To be creative.

JEREMY: If God intervened [as often as we’d like,] would [humans] actually have autonomy? None of this to diminish any suffering and pain and tragedy in the world is complicated. But [God does seem to originate the idea of] releasing [your creation] into the world and letting it be.

LIZ: It's notable that the most ancient artifact of God that we have is a book. It's words written by human authors about the deity. [And perhaps by the deity in some obscure, indefinable way?] That doesn't mean that God doesn't show up [in the Bible], but I tend to resonate with Karl Barth's view that the word of God becomes the word of God to us. …On its own, the book is just a book. But when you read it, searching for God, God may appear there.

…in that way the Bible's more like a sacrament than God being enshrined [with]in it.

JEREMY: That makes me think that the ongoing interpretation and the practice of engaging with this [book] actually elevates rather than diminishes the authority of this work. That authority doesn't have to be dependent on a particular interpretation [or] framework which logically fits [everything] together… until you remove one piece and then it collapses. … By proxy, this ancient artful, God-inspired work. We do not have to idolize this book, … put[ting] this work on the same level as God, but [instead it] becomes a pathway to engage with the divine.

LIZ: I think that takes some of the woo-woo magic out of the book. And I think that's why conservatives don't like it. But it's meaningful to me, as someone who does believe in free will, who believes that it matters that God respect our autonomy.

You know, Jesus knocks at the end of everything. The apocalypse is here in the book of Revelation, and Jesus is not breaking down the door. Jesus is knocking.1 That communicates so much respect for us as individuals, autonomous individuals with our own wills and minds and desires, to have God who, at the moment of judgment, is still knocking on the door. That means a lot to me.

I see the Bible as the same kind of book. It is invitation, it's not demand; it is inspiration, it’s not a revelation forcing itself upon you. It’s important to me that there be autonomy even in how we engage with God. God is respectful of us.

Making Space for Our Audience’s Experience and Interpretation of Our Art

JEREMY: I love the idea of invitation. We're not, and this might be dating myself, but as artists, we are not uploading our album onto your iPods by force. You know, Apple puts out the U2 album and decides everyone has to have this music [and so it appears in apple playlists and devices]. God isn't [demanding], …just pushing [Themself] into your consciousness, forcing you to obey or disobey. There's an invitation.

That's helpful even in the creation of art. [I’m inspired by] the idea of creating an invitation to your viewer. As a visual artist, I realize that most people spend a maximum of three seconds looking at any given piece of art [online], whether that's on my social media or on my website. There's a reality of our digitally connected world where people are quick in their [online] experiences…

LIZ: Or maybe, inattentive?

JEREMY: Inattentive, distracted, it's a multi-screen era. You know, we're looking at our phones while we're watching TV while we're doing something else. So… the goal oftentimes is attention. The goal is presence more than attention. You want to create something … recognizable—maybe [that’s] a composition, maybe it's a figure, something that will capture attention, but then also… keeps someone [looking].

And I know this is a horribly pragmatic way to, to think about crafting art, because it considers audience [so directly]. But it’s an invitation. [Make your work with something] like a beacon. It could be color, it could be a figure, it could be a composition that hooks somebody. But [once they’re hooked, they should be able] …to discover more. … So that's often a goal of mine as I make collage and I make artwork in different mediums is give viewers a simple entry point. But then, if they were to purchase this artwork and hang it on their wall, could they continue to discover something new? I hope the answer is yes.

Friends, thank you for listening/reading along with this short series about the artistic process. If you’ve enjoyed it, will you let us know?

You can support our work by buying the book, Knock at the Sky: Seeking God in Genesis After Losing Faith in the Bible, or by following Jeremy (Instagram) and myself (Threads, Instagram, Facebook). We will also have risograph art prints for sale soon! :)

About Jeremy and Liz

About the Author

Liz Charlotte Grant is an award-winning essayist whose work has been published in The Revealer, Sojourners, Brevity, The Christian Century, Christianity Today, Hippocampus, Religion News Service, US Catholic, National Catholic Review, The Huffington Post, and elsewhere. Her essays have twice won a Jacques Maritain Nonfiction Prize. She also writes The Empathy List, a popular substack that has been recognized by the Webby Awards (‘22, ‘23) and the Associated Church Press Awards (‘23). Knock at the Sky is her first book.

About the Artist

Jeremy Grant is a multi-disciplinary artist whose work is rooted in contrasting modes of natural and mystical experience through a practice that bridges association and obfuscation. He has exhibited work regionally in Colorado since 2008. His 2019 film “Remnants” was exhibited at the Supernova Film Fest, and the Denver Film Festival. He holds degrees in Graphic Design and Illustration (John Brown University, 2007).

[American, b.1985, Monterey Park, CA, USA, based in Denver, CO, USA.]

Revelation 2:20 reads, “Here I am! I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with that person, and they with me.” (New International Version)