the Empathy List #117: Church is hard for Marcie Alvis Walker, too.

A conversation with Marcie Alvis Walker of @BlackCoffeewithWhiteFriends about family dysfunction, white supremacy at church, and learning to parent the hard way.

Hello friend, Liz here.

Very few Christian authors write as raw about family as Marcie Alvis Walker does in her debut memoir, Everybody Come Alive. It’s tricky to write about family life, and Christians, in particular, prefer to hide the nuances of dysfunction, inheritance, and adoration that define family-of-origin relationships.

Why? Because it’s simpler. Because admitting our ambivalence might make us look bad—or might mean we are bad. Because nobody’s exactly sure what it means to “honor your parents,” anyway, in a wealthy, individualistic culture like ours. Does honoring mean we keep family secrets? Is it disloyal to find fault with your parents’ way of raising kids? When should we tell-all, if ever?

Alvis Walker prefers to tell the truth in public, and I admire her for it. Her memoir in essays chronicles her bifurcated growing up as an African American woman in the Midwest, the youngest and blackest daughter of a stunning, complicated, mentally ill woman named Miss Nada—herself the “black sheep” in her family. Marcie grew up halftime with her mother on a black city block and halftime in a white neighborhood in Ohio with her grandparents (she writes that her grandfather could “pass” as white). Conceived through an affair, Alvis Walker received the full force of her mother’s attention and her conservative Baptist grandparents’ criticism. In one house her blackness was celebrated; in the other, it was denigrated. But in both homes, Alvis Walker experienced abuse that took years to untangle.

Even so, I’ve never read a more joyful dysfunctional family memoir. Alvis Walker’s lyrical language, her empathy and nuance in approaching the characters of each family member, and her own willingness to admit her mothering errors make the narrative sparkle. I cried, I laughed, and I will be keeping this book on my bookshelf and returning to its pages in the years to come.

I interviewed Marcie more than six months ago (!!!) and am finally able to share it with you. (Marcie, thanks for being so gracious with me.)

She and I get into it—we talk weird evangelical megachurch culture, the coded “excellence” of private Christian schools, how we’ve recovered from family dysfunction, the unique burdens placed on black mothers within our society, how mothering is hard IN GENERAL, and the challenge of belonging to a church when your faith doesn’t fit into normative boxes anymore.

Marcie is down-to-earth, hilarious, and a damn fine writer. If you haven’t bought her memoir yet, I recommend it. (But you can follow our conversation even if you haven’t read the book yet.) You’re in for a treat. ;-)

Thanks for reading, my friends!

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

Marcie Alvis Walker on Evangelicalism’s White Supremacy Problem, Healing from Family Trauma, and Learning to Parent our Kids the Hard Way

“The Bible is Full of Dysfunctional Families”

LIZ: Marcie, there are not that many memoirs in Christian publishing, and even fewer memoirs as honest and raw as yours… so, firstly, I just want to thank you for your transparency! Your story moved me and I connected with it as someone who also grew up within a dysfunctional family-of-origin.

MARCIE: Family is an idol in a lot of Christian families—there’s talk of your family, you as a parent, the legacy that your parents hand down to you, the wellness of your family.

In American culture, we emphasize family more than community. But [Christianity] was always supposed to be this communal experience because the people in the Bible are nomadic and communal and they rely upon one another. It was survival. But we [American Christians] are so individualistic. The Bible characters would not recognize “family” as we do. They would be shocked that we are so nuclear in the way that we parent and live, by how many of us live nowhere near the ancestors, don’t even know where the elders are buried.

It’s also so strange to me because the Bible is full of very dysfunctional families, yet when we talk about God, we don’t talk about that. I had never found a story in any Christian bookstore that felt like mine.

Halftime Baptist, Halftime Free Spirit

LIZ: Speaking of family, your situation growing up was unique. Your time was bifurcated between Grandma’s house (dad’s parents)—where you also went to school—and your mom’s during breaks and weekends, split right down the middle. So many parts of your life were shaped by this duality, including your religious experience. Both your mother and grandmother were very religious, but they had these different flavors and expressions of faith—could you describe that?

MARCIE: So, I was raised in two different households. My book, Everybody Come Alive, centers on me integrating these distinct parts of me. Mostly I lived with my grandparents in an all-white neighborhood in the suburbs, and that’s where I went to school because the schools were better.

My grandparents were very traditional conservative Baptists. My grandmother stayed home and took care of me and my siblings. My grandfather worked for the post office, a job he got because he could “pass.” He was a very light-skinned, greenish-blue-eyed man. So, people didn’t always read him as being African American. They were Deacon and Deaconess at their church—and it was a classic black Baptist church. We were at church all day Sunday—Sunday school in the morning through dinner . I was raised with their conservative, patriarchal, black faith.

LIZ: Patriarchal, but very female-centric in some ways, right?

MARCIE: Yes, and I think that’s true for all churches. If women left the church, there’d be no church. There’d be no way that the church could go on.

LIZ: Because we’re doing everything in the background to make it run.

MARCIE: Exactly. So, that was one half of my life. The other was with my mother. For summers and Christmas break and weekends, we would go to Cleveland, Ohio. My mom’s house was in a working-class black neighborhood—the dads worked at the factory, at Ford, at a steel mill. And the moms were nurse’s assistants, factory workers, or maybe they worked downtown at the mall.

My mother came from tent revival West Virginia—black hillbilly country, up in the hills. We’d go visit her mom (my maternal grandmother) for the summer [and] be warned about the bears that might come down from the mountains, be warned about the snakes underneath the porch—like, hill-billy West Virginia. All grandma did was church, which we kids found boring, so, we didn’t like visiting grandma.

LIZ: Was that grandma more Pentecostal?

MARCIE: I think? Her church was not as reserved. On the conservative Baptist side, they’ll “Amen” you, will let you know when you’re preaching good, and they’ll help you out if you’re not doing well. You’ll hear someone go, “Help ‘em, Jesus, just help them.” But in general, they’re more reserved, so you’ll have a tambourine, you’ll have an organ, you’ll have a piano. And we’d pray for churches with a drum kit or electric guitar, like, “Lord, Jesus, we love Mount Zion First Baptist, Lord, we pray for them to have the Holy Spirit of self-control…” Especially if they were speaking in tongues.

LIZ: [Laughs] God help those sinners. So, no drums, no electric guitar, and certainly no smoke machine.

MARCIE: Right, and you’re not going to be running up and down the aisles either.

But my mom… she was the scorned woman on the block—the divorced single mom who was beautiful, had lovers, wanted to have a good time. She was the type to plant a garden just like all the other women in the neighborhood, but between her collard greens and tomatoes, there would be weed growing. She also had a mental illness. She was that person.

So, she was always being invited to church by neighbors, and she would bring us kids along to Pentecostal churches, Church of Christ churches, even a Jehovah’s witness service. My mom wasn’t fearful of any of that because she felt herself sort of “outside” the church. As part of her illness—she was schizo-affective—she believed that she had a very special connection to God that was beyond church.

So, when we went on excursions to church, she would be pitying the people around her. She would watch televangelists and debate the TV because she knew God better than Pat Robertson [of the 700 Club] did, even though neither of them what made sense.

But then my mother would have these real moments of genius. There was this one time a pastor was bringing down a sermon, saying, “If you’ve seen the Lord Jesus in your life, stand up, rise up…” Everyone around us is standing and whooping and hollering. And my mom just sat completely still, staring around, looking at them sideways like, “Ridiculous.” I was maybe twelve and mortified that my mother wasn’t standing. I said, “Mom, stand up. You’ve seen the Lord Jesus, my God.” And my mom goes, “Ain’t nobody in here seen Jesus.”

LIZ: She wasn’t wrong! And I have to say, though your mom is complicated, it’s evident in your writing that you adored her as a kid—and that you still do.

MARCIE: I do. That’s why I refer to her as Miss Nada, not mom, not Nada. Calling her miss is a way of respecting your elders in the black community like saying, sister so-and-so at the church. You don’t call people you respect by their first name. There’s a clip of Mother Maya Angelou taking questions on a tv show, and a young girl gets up and refers to Mother Maya as “Maya,” and she stops her and tells her, “Oh, no, honey, you haven’t lived long enough to call me Maya.” Like, once you’ve been through it, then you can call me Maya.

I grew up with that kind of understanding of my mother, too. I respected her more as a woman than I did as a mother. She was a terrible mother, but she was a wonderful woman. Both things can be true.

“Imagine Mothering with 400 Years of Slavery on Your Back…”

LIZ: One of the major themes of your book is mothering—your relationship with your mother, Miss Nada; her relationship with hers; you with your grandmother [father’s mother]; and you with your own child, Max. You’re documenting, what does it look like to be a [nurturing] mother when I haven’t been mothered this way? How do I make sense of the mothering I’ve received?

In particular, your book drew out the unique experience of black motherhood. For example, you quote Malcolm X: “The most disrespected woman in America is the Black woman. The most un-protected person in America is the black woman. The most neglected person in America is the black woman." And Malcolm X is drawing on earlier writings like W.E.B. Dubois’s poem, “The Burden of Black Women.”

So, I wanted to ask you broadly—realizing you cannot answer definitively for anyone but yourself—what do you understand to be the unique burden of black women, and in particular, black motherhood?

MARCIE: That’s a hard question to answer, just because motherhood is so nuanced and it’s not monolithic. But what I'll say is, whatever a non-black person or parent is facing…I always think, well, imagine doing that with 400 years of slavery and police brutality and systemic oppression on your back.

Our history as slaves meant our bodies were to be disciplined into submission; so now, as a black mother, the hard thing for me is to let my kid move freely without fear of me trying to quiet or mold their identity to suit the normative culture. I’ve really appreciated the conversations I’ve had with parents of children who have autism or who have a disability because when you’re a black mother, you face similar disadvantages, and you don’t get a whole lot of sympathy. The world is expecting you to make sure your child is not seen or heard or disturbing whiteness or normative culture.

I think the media missed this when they covered the story of the young boy [Ralph Yarl] who rung the wrong doorbell [and was shot through the door by a white man]. The man who shot that boy comes from a long tradition of men who look like him who never had to have a black boy at their door unless they had sent for one.

I’m sure that young man, when he went up to that house, was rehearsing all the things his parents have told him to say so he could present himself in the world as non-threatening. Presenting himself that way is not just polite, but should keep him safe. But it doesn’t keep black kids safe. Just his being there, that made the white man fearful enough to respond with a gun.

Well, as a black mom, I feel that my job, like [Yarl’s] parents, is to make sure that this kid never feels the fear I hold for them, that they never fold into themselves because there’s a man who is afraid on the other side of the door.

But that’s also risky. The risk reflects a society that isn’t safe for our kids. Our kids can be the most polite, the most educated, and it might not matter.

LIZ: You’re saying, there’s the normal customs of our culture, but then there’s an extra litany taught to black kids because of an American culture that doesn’t protect their bodies.

MARCIE: Right. The hardest thing as a parent is knowing that there’s no amount of parenting that can make the world safer for your kid.

Private Christian School and Over-involved Parents

LIZ: You’ve talked not hiding black identity. You mentioned your grandfather could pass which is how he got the post office job. A lot of the interactions you record with your grandmother reflects her efforts to quash blackness out of you, while your mother does the opposite, encouraging it. So you write about the internal conflict you felt between the two messages. That conflict seems to culminate when you’re a mother yourself and you sent your kid, Max, to a Christian private school.

I actually attended a Christian private school myself. And in my experience, the hypocrisy and the wealth and privilege of that space was overwhelming. I can imagine it’s that much worse if you are a non-normative identity entering that space because the pressure to conform to whiteness is so high.

MARCIE: The administrators were always talking about “excellence”—our students, our families are striving for “excellence.” But who gets to determine what’s excellent and what’s not? Usually what’s not excellent is any way of thinking that the community calls foreign or that they dislike. These communities can become so insular. They decide what is “excellent” (good) and not, meanwhile, no one is checking the real evil happening. That’s why you have the high amounts of church and spiritual abuse, because there are no outsiders welcomed in.

For example, I remember a prayer meeting at my kids’ school where parents prayed for higher enrollments and called that “evil.” But low enrollment isn’t evil; that’s just a challenge. Meanwhile, in my kids’ junior year, every kid had to write a thesis debating the pro- and cons- of slavery in the U.S., which they presented to an audience board. This was a regular part of the curriculum, and before I confronted the school about it, no one ever had. (Fortunately, my kid didn’t participate; we left after 10th grade.) And another friend’s daughter was getting harassed because her senior thesis was about solutions for rape culture on college campuses, and apparently, others didn’t like it.

LIZ: So, in that culture, kids could get away with saying anything, could push boundaries because there weren’t other people in the room to say, “Wow, that’s racist.” I see this as a huge issue in dominant culture in general. For minorities, building smaller communities probably is helpful, but I don’t think it’s helpful or healthy for dominant culture groups to create these insular communities that don’t take other perspectives or cultures into account. That just becomes another way that we segregate.

MARCIE: Something my mother gave me was a model of individual identity as a woman beyond motherhood. She was a free spirit, she was very creative, and wondrously herself. I’ve tried to be that for Max. Because only claiming the identity of “mom” can burden a kid. If your only identity is wrapped up in them, then they may resist separating and standing alone as adults.

LIZ: To be fair, I’m not sure mothers today have a good example of that kind of independence from our kids. We’re encouraged toward over-involvement. It wasn’t always like that, though!

MARCIE: Oh, goodness, I remember going to the park and meeting a friend there, and there were no parents.

LIZ: Back in the 80s, kids just wandered around. Like in Stranger Things, they’re just on their bikes all around town. Do their parents have any clue where they are?

MARCIE: My husband and I keep joking that they keep setting these movies in the 80s because how else would a kid today have an adventure?

Rejecting The Faith of Our Parents and the Family Dynamics of “Deconstruction”

MARCIE: At the private Christian school, I was constantly talking to stressed out moms who were talking about how well or not well their kid was doing in school, how they ranked, and such. Since then, I have often wondered, what happens when those kids go off to college? How do those moms spend their time? Because they put so much into this one identity. So, what happens after the kids leave? Or what happens if the kid decides they don’t want your faith—are you going to be okay?

LIZ: I think this is exactly what you’re seeing now within the Evangelical church… a lot of my readership are those who have “deconstructed”…

MARCIE: For people of color, I say “decolonizing,” rather than “deconstructing.”

LIZ: And that’s really what it is, though white folks are slow to catch that train. But the dynamic with Millennials “deconstructing” is that our Boomer Christian parents are losing their minds because their Millennial children are “deconstructing” faith. Our parents made this insular space for us kids growing up, and now we’re saying, not only do I not want your faith, but I think the faith you raised me in damaged me, perhaps it was even abusive. Evangelical leaders—I’m thinking of Dobson—even promised our Boomer parents that if they parented like this then their kids would turn out like that. But that’s just not how human beings work. Human beings don’t conform to formulas.

MARCIE: I think you’re exactly right. We’ve definitely dealt with this in our own family. My husband is a red-headed white British boy from England. His family moved here when he was in tenth grade and… we’re estranged. It’s very difficult for them to accept what’s true for him, what’s true for me. And I have a lot of sympathy for them because I don’t think they intended to harm him. And it’s a lot for us, being a mixed-race couple. It’s very hard for them to understand that “oh my gosh, I have tendencies that are racist and harmful and I need to work on that.” For them, they’re like, “No, no, no, I have Compassion [International] kids that are brown, I listen to Gospel music, I just did [a] Priscilla Shirer [bible study]…”

It’s very hard for them to understand the damage of a color-blind theology. And it’s because they were told that they were being good. That a color-blind theology was good and honorable.

They’re like, “Wait, now you want me to change? At this age? I have been with this life group for forty years. I have been at this church for forty years…and now you’re telling me I’ve been doing it wrong?” That’s difficult, I get that.

Parenting Failures and Learning from Our Kids

MARCIE: Now that Max is 21, I’m already getting reports [about what I’ve done wrong as a parent], and that helps me to stay compassionate toward my extended family. Already I’m like, ”Oh, gosh, I’m sorry, we got that wrong. Yep, I said that, I believed that.” And I have started to tell Max, remember, I had never been a parent before you got here, and at every new age, I’d never been a parent for a kid that age either. I was figuring parenting out as I went along, and I was just as clueless as an adult as Max was as a child. I’m so grateful that Max is very generous with their forgiveness.

LIZ: It’s tough to be confronted by all the stupid things we did as parents.

MARCIE: Like sending Max to that [Christian private] school! I thought that school was the safest place on earth for them—because the brochure said it! The brochure said it was going to be okay, and I believed it.

LIZ: And don’t we want to believe that, as parents? That it’ll be okay?

But before we move past it, I just want to point out that the distinctive thing between other generations of your families and you and Max is that you are willing to have the conversation with Max about what you did wrong… and then to change and say sorry for ways you hurt them.

MARCIE: No joke, I thank Mr. Rogers and Oprah for that. I’m a Gen-Xer, so my parents didn’t have therapy. Therapy was like, who does that?

LIZ: No one. Literally, if you are in a psychiatric ward, that’s when you do therapy.

MARCIE: Having conversations about your childhood feelings? Nope.

LIZ: They’re like, why would I ever think about my childhood again? It was terrible.

MARCIE: My generation—growing up in the late 70s and 80s—it was all about our feelings. Mr. Rogers said our feelings mattered. Saved by the Bell said our feelings mattered. And then Oprah was like, your feelings really matter. So I’m lucky cause I’ve been able to hold space for Max.

LIZ: I admire the empathy you’re extending toward your in-laws. I’m interested in this question of inheritance passed from parent to child. What would you say that you’ve inherited from your maternal ancestors? And also, how have those inherited pains and joys, how have those influenced the way you raised Max?

MARCIE: This answer is twofold for me. Because Max has bipolar disorder, and it’s hereditary. So, when I first heard the news of their diagnosis, I went through a few dark days. But my sister reminded me, you’re not the child, you’re the parent. So, now you can be what you always hoped mom would have been to you. I can be a good mother to Max and support them in ways my mother was not able to support me.

LIZ: So, you mentioned in the book that there was emotional abuse from your grandmother, some neglect from your mother, and those things were hard. How have you sought healing, and how has that healing affected your mothering?

MARCIE: I went to therapy when my mom went to jail. [During a psychotic episode after Marcie had moved out of the house, Nada was attacked by a friend who she killed in self-defense. So, she was sent to jail. You can read the entire story in Everybody Come Alive or see a brief snippet on Marcie’s blog]. The first thing I said in the therapist’s office was, “Oh my god, I don’t know what’s going to happen to us. I don’t know how we’re going to make it.” She was like, “Who is ‘us’? Cause it’s just you here. This session is about you.” That helped me separate myself from my family, to not be in this codependent thing where my family’s problems controlled my world.

That started me being a better parent to Max, too. In fact, parenting Max was healing for me. My kid is very sensitive in all the best ways. I tell the story of going on childhood walks around the block with them, and it was always this expedition because they knew all the names of the trees, they knew the names of the different bugs, they saved worms on rainy days. It would take us forever to just get to a place, you know? And they hugged trees. They would hug a tree and go, “Keep growing!”

Being with Max, I got to see myself. I would say to myself, that’s what a four-year-old looks like. I was four when such-and-such happened, or I was ten… I would never want to put that on my kid… and it helped me to realize that I also deserved to be protected. As protected and loved and cherished as Max. I had always believed that what went wrong in my family was my fault because that’s what kids do; kids take on blame that isn’t theirs. And watching Max grow up, I was able to understand, no, it was never your fault, Marcie.

LIZ: I had a very similar experience with parenting. You’re watching your child and you’re able to map to your own experiences as a child and to say, “Actually, that’s too much for a kid to handle. Maybe that was inappropriate for me try to manage my parents’ emotions.” And being able to push back against enmeshment and dysfunction, and say, “I’m going to individuate, and that’s actually a good thing for me as a human and for my parent.” My kid’s individuation is good, and so is mine.

Why is big C “Church” So Difficult?

LIZ: I am moved by your advocacy online, especially your writings about white supremacy in the church, particularly the white American Evangelical Church. I used to be evangelical and now I don't know what I am anymore. And I have no clue how to belong to a church now! This church question is one I keep circling. So, I guess I’m wondering, how have you made peace with experiences of racism or pain you’ve personally felt at church? Have you found a church to belong to?

MARCIE: I’m with you sister. No, I’m not involved in a church right now. Church is hard for us, too. There was a time I would have believed that not going to church was sacrilege. A complete impossibility. I had been such a church girl. But for me, whatever church I align myself to, I am basically signing my name to their beliefs, their practices, even the ones that I don't agree with. And the harm that they do. So, I worry about that. I never want readers to feel like I have an agenda. It doesn’t feel like I could be trusted then. And I often wonder how that would affect my kid, too, who is queer. I don’t ever want them to say, mom says this, but her church says that.

So, I guess I’ve made peace with God. I’ve even made peace with the Bible because I’ve done enough study that I understand that God is bigger than the Bible, and I understand that the Bible is not exactly what I was taught that it was.

I’ve learned to look for God beyond the Bible, to look for God in people, for a moving spirit within each of us, the reflected light that we shine, the divinity, and that way I’m seeing God everywhere and not using the Bible as a reason to erase someone’s dignity.

What I haven’t made peace with—and I don’t think I should make peace with—is the church. Because I don’t think you should make peace with your abusers or with institutions that are abusive. And I really am trying to disrupt the church, to break everything what needs to be undone. Am I the authority on deciding what should be undone? I would say, no, not solely. But speaking from the edges of the world as a person who’s marginalized as a woman, as a black person, economically and even academically because I don’t have an advanced degree or even a [single] degree, I feel it’s important to remind people that we at the margins are also holy reflections of God.

Way too often, people like me are dismissed because it’s easier for the church to grow as a corporate institution if they ignore the margins and the people who don’t fit.

I’m talking about the big C church now because I know there are churches who really are trying to be what even a nonbeliever would hope a church to be. And I wish that there were more churches like that.

LIZ: What’s missing in the American church? What would a compelling, safe church look like, in your opinion?

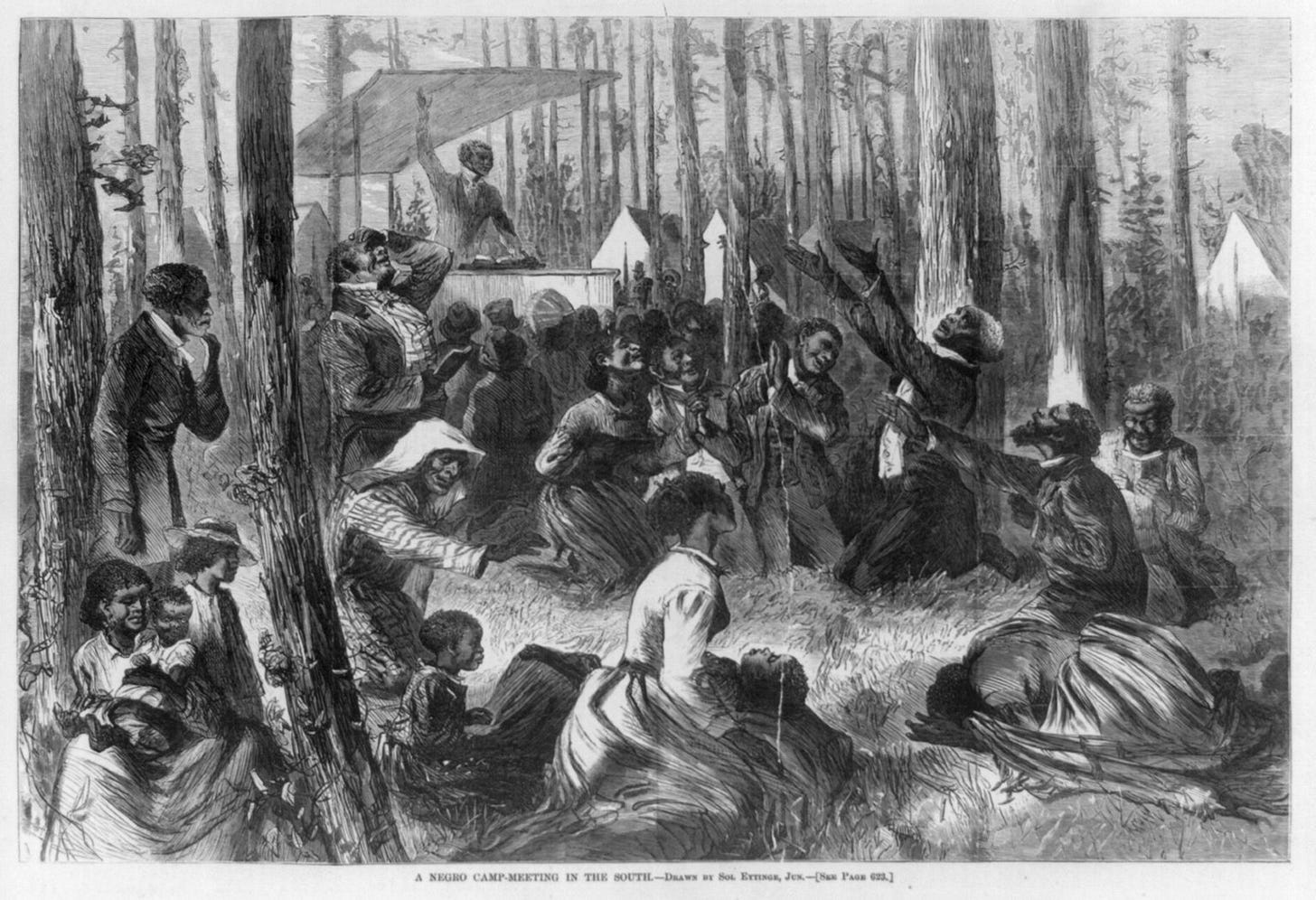

MARCIE: I think of hush harbors. These were places where enslaved people went to worship freely, away from the enslaver and the enslaver’s limitations on their worship. Those hush harbors turned into little shanty churches and those churches turned into the black church which was needed and created out of oppression because they weren’t allowed into the white church. Maybe that segregated moment was a great gift to African Americans because we were able to create a church out of desperation—because our people were dying. We did not create a church out of obedience or out of “the Bible told us to.” Our people were not free, so they needed a safe place to come and hear that they were human.

These churches existed so that sister-so-and-so who cleaned the white pastor’s house all week long and took care of his children and made sure that his wife got plenty of sleep and was able to be the “first lady” of her church while Sister Williams was ironing and keeping the white woman’s house running—our church was where sister Williams could come to put on a nice hat, a nice dress, and be addressed as Sister Williams. She could receive honor. She would not be called not “Mami,” not “girl,” but she could be respected as a grown woman and seen as holy.

LIZ: That is such a different vision for church than what’s put forward by the American megachurch movement—the Tony Robbinses, Bill Hybelses, Rick Warrens who are asking, how do we build an enormous corporation? Not, how do we build a safe community for particular weary humans?

What you’ve described is centered on actual service of the people who attend—the leaders in service of the congregation, which is the model of shepherds that we see in the Scriptures but is so rarely followed in practice. Our biggest churches seem to be about power or money, not people. The elder boards and capitalism and huge auditoriums… what is that actually about?

But Jesus tells the story of the shepherd who goes after the one lost sheep. So, if that is a story that defines who God is and what the kingdom of God is like, shouldn’t that be the defining feature of the American church as well? In other words, if the humanizing of actual humans who are outcast is not happening, then we should question whether it counts as “church,” according to Jesus.

MARCIE: Exactly, that’s the center. The black sheep are worth counting. Our common humanity should always be the goal of church. I’m dying to find that. I’ve heard of a few people who are putting churches in communities not to convert souls—not for a “bait and switch”—but sincerely to build a loving place for people who are exhausted and rung out, raw, hung out to dry, so they can come and be nurtured.

LIZ: It can seem that most American churches are happy to convert you either to heaven or Republicanism. But I admit, like you, I grew up at church. It was a big part of my identity. So, there’s still a part of me that wonders, how could I not go to church? What does that say about me now?

MARCIE: Yes, yes! How do you not go?

LIZ: And I miss those relationships. I’m the extrovert who’d still be standing around chatting an hour after church had ended as my hungry kids pulled at my shirt to get me out of there for lunch. What I don’t miss is working at church—I had the “luck” to intern at an Acts 29 church at one point, which was its own kind of hell.

MARCIE: Oh, no! I worked at a megachurch myself, a Willow Creek association church in Texas, and that’s like seeing behind the curtain in Oz. I’m so over the “hype” church model. Our megachurch had a U2 Easter and a Beatles Christmas with lights, costumes, the whole nine. And my husband is telling me not to forget to mention the smoke machines. I don’t want any more U2 Easters, but I also don’t want monotone. I don’t know where to find that. I feel like Stanley from The Office talking about the Office Christmas party: “I just want Christmas is Christmas is Christmas.” I just want that. And I don’t know where to find it. I also don’t want my activism to become church.

I wish “On Being” could be church. I just want to go sit and listen to someone tell me something beautiful about astronomy. I wish this, what we’re doing right now, could be church. Maybe it is. I hope so.

About Marcie Alvis Walker

Marcie Alvis Walker is the creator of the popular Instagram @BlackCoffeewithWhiteFriends. She is also the creator of Black Eyed Bible Stories Marcie Alvis Walker . Marcie is passionate about what it means to embrace intersectionality, diversity, and inclusion in our spiritual lives. She lives in Chicago with her husband, her college-aged kid Max, and their dog, Evie.

Buy Marcie’s book, Everybody Come Alive: A Memoir in Essays.

ICYMI, I’ve interviewed other like-minded progressive Christians, such as…

Trey Ferguson, author of Theologizin’ Bigger,

Tim Whitaker, founder of the New Evangelicals,

Sara Billups, author of Orphaned Believers,

and J.S. Park, author, hospital chaplain, and father to an adorable toddler ;-).