the Empathy List #89: J.S. Park talks Family Trauma, Church Abuse and Hospital Chaplaincy

Deconstructing Evangelicalism with author and activist, J.S. Park

If you enjoy my emails, would you forward this one to a friend?

Hello friend, Liz here.

I’m coming to you today with another story of a fellow “deconstructor.” (Remember this series, in which I interviewed Tim Whitaker of the New Evangelicals and Sara Billups, whose book Orphaned Believers releases soon? It’s been A WHILE.)

I first encountered J.S. Park through his social media presence—and unlike most of the Internet, he is more presence than performance. J.S. is kind, even to his detractors. This stands out because he’s also a seminary grad, and he’s also a dude, making him a defacto “theo bro,” which is a category that doesn’t have a high reputation for nuance or openheartedness, especially toward opponents.

Truthfully, my own ragged church history makes me wary of male MDivs. But J.S. is not like the others. He’s a hospital chaplain, a man of color and the son of immigrants, and he’s found a way to speak truthfully while still acknowledging the humanity of each person who interacts with him online.

He calls himself a “bridge-builder.” That is certainly true, as you’ll see in our conversation below. But I think that description undersells this man’s unique call. He has practiced how to be with another human. Listening and noticing another human without agenda or coercion is perhaps the very hardest skill to learn. And J.S. has the gift.

As he told me in our conversation, “Building the bridge is critical and important. If there’s a way that I can speak that’s not about changing minds but about opening hands and hearts, about expanding and broadening, then I will expend the labor to do that.”

Church leaders like J.S. give me hope that Christianity isn’t rotten to the core, that there are still those in the tribe speaking the truth through genuine and painful care of whoever’s receiving their words, and that there are those who are willing to bleed in order to bring the radical Christ to those who need Him most.

Ironically, the ones who seem to modeling Christ best are the ones who were first wounded by Christ’s church. Fitting, I think.

Anyway, please read and go follow J.S. everywhere online (I recommend his Instagram, personally). And buy his book, too, while you’re at it.

Here’s to making the Internet kind again!! ;-)

Thanks for reading.

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

J.S. Park, author and activist, on being the son of immigrants, surviving family and church abuse, and how hospital chaplaincy differs from pastoral ministry

Family-of-Origin Trauma

J.S.: My parents divorced on my 14th birthday. My dad called himself Christian, though it was very hard to see. My mom, she was not and is not [Christian]. She said everything was true, you can take what you want. My grandmother, who lived with us, was a practicing Shintoist—she prayed at a shrine with incense and beads, all of it. So my religious upbringing was pretty diverse.

[The divorce] was pretty rough. My family was pretty definitive on rules… but they each had different instructions and different rules [for me] so it became very confusing. I had different sets of rules for everywhere. I became different people depending on where I was at, and I had different groups of friends depending on where I was at.

I didn’t just code-switch my voice, I code-switched my whole core. I was a beige chameleon.

LIZ: That sounds overwhelming.

J.S.: To paraphrase Change-Rae Lee, who wrote Native Speaker, “I just become a mirror. And I stoke the vanities of the people around me. Because you know, I have none of my own.”

…I had to be that person who was the center of calm wherever I was at. It was such a turbulent upbringing—not to mention the poverty and the abuse and violence, all of it.

A Childhood of Code-Switching

J.S.: My parents were immigrants here. I was born and raised in the US. But English not being my parents’ first language, I noticed that people would try to rip them off all the time. Maybe they looked like—and I say this with quotes around it—“clueless foreigners,” so they just were bamboozled and hoodwinked all the time.

For example, my Dad tried to outright buy this building. He's a Taekwondo instructor and he tried to buy this building [for his business]. And it turns out there were tens of thousands of dollars of back taxes owed on this property, and the [owner] had built that [debt repayment] into the contract. They were just going to sell it to him like that for my father to repay. If my dad hadn’t had his lawyer friend looked over the contract, he would have bought it without knowing.

Things like that happened all the time. Also spam mail. For example, my parents just start clicking. They don’t think twice about it: “I better fill out this credit card number, I better give them what they want,” they’d think. So I became a scam translator for them.

This is the experience of many second-generation Asian Americans—building a bridge from our parents to American culture and American society so that they can thrive and find livelihood here.

It's a similar thing as when our parents find new technology. We, as their kids, have to sort of translate [that technology] for them. But for me as a second-generation immigrant, it broadened into all the ways in which my parents interacted with people, with money. In that sense, my bridge-building propensity came about because that I wanted to see my parents safe and I wanted them to be okay. I absolutely know they did their best. But I was their mediator or translator or representative.

The other layer was that they were abusive at home—physically and verbally abusive. It was very, very confusing. A complex relationship. So I'm trying to help them, to keep them happy and safe, while at the same time, being harmed by them. While at the same time, I’m assimilating myself to American culture. It’s a lot of layers.

A Long View on Recovering from Trauma

J.S.: I'm still in recovery and I think there is a lot of recovery left.

There are certain family members that I currently do not talk with. Reconciliation, restoration, repentance, all of that, that's all important.

But self care is important, too. Boundaries are important. Our limits are there for a reason and we're human and we have certain capacities and, of course, needs for safety. [I ask] myself, …at what point is this bridge building becoming people-pleasing or codependency? When I'm building a bridge toward my parents or others, there is good in [that urge]. But also, resilience born out of dysfunction can become its own trauma.

It's still very very difficult because there are voices that pop up that are like, [are] you now forsaking kindness? [But] there's a difference between being kind and being nice. If I am just remaining friendly with someone so that there is no disturbance or disruption in the relationship, then that's a false truce and it's all a performance. And I just got tired of doing that dance because it just felt like I was on my toes all the time and my ankles were hurting real bad. I can't do these spins anymore. This is thin ice, and there’s sharks under there.

One of my favorite books from the last year is Latasha Morrison's Be the Bridge. It largely covers racialized trauma and racial injustice in the black community. And when I read the book, she does cover the anger—the feelings of injustice, the facts of injustice—and she starts weaving in themes of reconciliation, restoration and repentance. I don’t think the burden of reconciliation ought to be on the victim [of abuse] ever. When I say repentance, I’m not talking about just signaling or brushing things under the rug.

LIZ: Right, the fake apology that goes, “Sorry you felt that way.”

J.S.: And there's a type of repentance that’s like, if I just feel guilty enough and express my sadness, then you should get over it. But actually, you just made it all about you again.

But I have really tried to find the good and keep the good [from my childhood]. This is not original. Because [experiences like mine] can also result in “fruit”—for example, eventually I understood, there's a healthier way to build a bridge.

But I loved Morrison’s book because it has such a hopeful view of the horizon. Her book came at the perfect time because I was so upset about all the injustices happening and that was shortly after the murder of George Floyd. When I read her book, there was so much upset and anger rightfully so. For her, of course, that’s a very personal experience. And I felt her anger, too. But it also brought the hope that we all need.

The seed planted today becomes the shade of the tree tomorrow.

LIZ: As in, the story’s not finished. You had these harmful relationships, but they taught you kindness, in a way. By not getting what you needed, you understood what you did need and what others need.

I love that image of the shade tree because it has a long view in mind. So what I hear is that you're not necessarily even planting for this generation, right? You're planting for whoever follows. Even if the fruit [of that family dysfunction] right now looks insignificant, who knows what it will be in the future?

Moving From “Lost” to “I’m Already Found”

LIZ: Did you have a very tumultuous relationship with God or was it just, “Nope, that’s my dad’s thing, and I don’t want to be like my dad”?

J.S.: I was an atheist. For me, as an atheist, there was a sense of being lost.

A lot of that had to do with my parents. Very early on, they told me that I was an accident. Meaning they didn't plan for me. So I spent a whole chunk life believing I was like a cosmic disruption and I was convinced of this.

So everything that I did good, I thought, “I'm earning my stay.” And everything that I did bad, I was like, “Oh my gosh, I am doing a butterfly effect on the timeline and messing up everything.” I thought I was knocking over the celestial dominoes of this universe somehow. I spent a long time believing that.

Embracing faith [meant understanding that] there is purpose. There is a love greater than anything that is contingent or measurable. I am loved. And I'm treasured and I was and am on purpose.

That’s not to knock on any of my friends with no faith. But for me, I can say this, I can say that it brought [me from] I have to earn my stay to my value is intrinsic, inherent, it is imago dei. I’m extravagantly loved.

I moved from a place of finding, seeking, lost, looking into I'm already found.

Some days [this is] still a wrestling. Because those old voices, always come back up—with mental health stuff and with depression and I have seasons of anxiety, too. There's always that voice [asking,] are you sure? Are you sure about that?

But that cosmic constancy… is the fact that God always is and is always for us.

Side-Hustled into Church Youth Group

I first started going to church in my senior year of high school. I played the drums for a few years at this Korean American church. Somebody asked me to be a drummer on the praise team. That's how it started.

I told the guy, is it a problem that I'm an atheist? And he’s like, no, just come to church to play the drums. So he kind of side-hustled, side-tackled me.

I would listen to the youth pastor’s sermon, which was kind of “in one ear and out the other.”

But eventually, it wasn't any apologetic or reasonable defense of faith [that brought me to faith in Christ]. It was just a love of that church—that community, and especially that youth pastor. I mean, [he was] so loving, so extraordinarily, remarkably loving and patient and no strings attached, just loved and loved and loved.

And I asked him a million questions. Then I extrapolated backward, like why are they so loving?

But if I were an atheist today and I went to church, what would happen? Would I have be loved like that? It’s scary for me to think about.

Going to Seminary as an Agnostic

J.S.: I was calling myself agnostic and I decided, against my better judgment, to go to seminary. ‘Cause I thought, with [a seminary] degree, I could help people. I saw the avenue of church as one of the best ways to do that.

I don't think I really, really embraced the gospel till I graduated from seminary. That was my mid-twenties or even late 20s.

[But] I would say my faith grew despite seminary. I went to Southern Baptist Seminary. Which going from atheism to a total 180 and to Southern Baptist world… was big whiplash. At the time, President Obama was president. And so I got to hear all kinds of interesting things from Southern Baptists.

LIZ: He was the Antichrist, right?

J.S.: Exactly. I met very wonderful Southern Baptists, for sure. And then others [seemed] to have a back room with a conspiracy cork board.

Experiencing Abuse at Church as a Youth Pastor

J.S.: [After seminary], I was a youth pastor at the same Korean American Church where my youth pastor had been, though he had moved on. I found out very quickly that this church was such a toxic leadership environment—abusive, harmful.

But I didn't have the names for that, so I just took it. I thought, this is the way it's supposed to be. I'm supposed to suffer for my church.

Gosh, I wish I could say this kindly or compassionately, but I think the leaders at that church were single-handedly responsible for putting me into the worst depression of my life.

Reflecting now on my experiences in pastoral ministry, I didn’t fit. And I experienced the abusive systems of both the Evangelical church and some of the very toxic parts of my own Asian American culture. It's poisonous. It's harmful.

I was [actually] let go at the end of five years [from my youth pastor role]. I was devastated. I would have died at that church.

And I remember my brother, who is not spiritual or Christian by any means, [and] I talked with him on the phone on the day I was let go. I was crying hard because I [had] loved that church. At least as far as I knew.

My brother said, “I've been watching, and I think this is the best thing that could ever happen to you.” That’s not always the best thing to say to someone who’s grieving, but now I'm so glad he said it because he was right. He was right.

LIZ: That sounds really painful. Especially knowing what a sweet place it had been for you and then coming back to it as a leader and finding it to be really toxic.

J.S.: Even now, I can hear the voices of those leaders. If they heard what I’m saying right now, they would probably be like you're too sensitive.

One of the guys [once] told me that I was being used by the devil. How do you get out of that?

Then I'm also thinking… you know, at that time, I was depressed. I was cranky. I was not myself. I do not think I was a good youth pastor.

But I've gotten messages from [former] youth students [saying,] “My life was a mess, but you were the one bright spot.” Messages like, “Thank you so much for setting me up for life and for the inspirational things you said.” My former students are now grown, married with kids. And I'm hearing that from them, despite what I was going through.

When I get those messages, I've literally messaged back to apologize—like, “I know, I didn't do everything I could, and I wish I had pushed harder for this, and that, and I wish I was more present.” Some of them have responded back, “You have nothing to apologize for, I don't even know what you mean.”

Somehow God still moved and worked and breathed in that place anyway.

LIZ: If you put yourself in their shoes… when you are in a dysfunctional setting, any kindnesses or attentions from adults make you feel like you haven't been breathing and now you can breathe again. It sounds like you were both gifted for those students in that time and it was hard for you. It can be both of those things.

J.S.: You're right, it was a very painful time, but seeing the fruit of it now… surely God was still alive in that place and working through me.

LIZ: And that is a mystery.

How Hospital Chaplaincy Differs from Pastoring

LIZ: So you've been a hospital chaplain for almost seven years after seven years of pastoral ministry…

J.S.: Sometimes feels longer than seven years. Just because the work itself is so hard. [And] I love it. It's paradise compared to where I was.

LIZ: It sounds like you have a lot of autonomy, which [is different] to the very hierarchical structures within evangelicalism and the Korean-American church you were in. What has it felt like to leave those Evangelical institutions? How has that shifted your personal relationship with the Lord? And also how has it given you new energy for ministering to people? …Because I think some pastors get stuck thinking pastoral ministry is the only ministry [worth doing.]

J.S.: When I was a pastor—and I would say that this is true of Protestant and in particular Baptist pastors—I was a preacher. I was imparting information. Believe this, agree with this.

The difference is, pastors are preachers, whereas chaplains are presence.

When people think of chaplains, they think, “Oh, you're like the angel death.” A chaplain in a hospital room, I mean, that's not good. “Am I about to get closer to God now? I’m not ready to meet God yet.”

But I'm just there to spiritually support. It’s sitting with someone, being present, being the center of calm.

There’s doctors and nurses, surgeons, specialists, this chaotic whirlwind of [medicine], and they all need to take information and gather and draw and collect and they all have a role. The chaplain is the one who comes in and doesn't ask for anything. I’m just here to hear your story, to ask, how are you feeling? How are you holding up? A lot of times, [my role looks like] the patient sharing their whole story.

When I enter the hospital room, I'm not on the hook to impart any kind of theology or information. I’ve heard—and I didn’t come up with this—that most people who have questions carry their own answers.

When I see a patient, very often, something in their own story or in their own faith tradition [can offer them] the tools and resources to cope with and to make it through [whatever] they are enduring. Certainly, I can support them. But I'm just with patients, not preaching at them.

That’s what a lot talk therapy does, too. At least in the hospital, psychologists don't always bring up faith though. If a pastor comes they often have the aim of [saving], like, “If you're gonna go to the other side, we got to make sure that you're saved.”

But as a chaplain, I'm running between [psychologists and pastors] in that mental health, faith and crisis counseling space. So I guess I'm a cross between like a priest and a therapist? A thera-priest?

Chaplaincy Teaches You to Listen

J.S.: And I believe that the chaplain training [I received] saved my marriage. At the time, my marriage was doing pretty bad. But the act of listening, the “being with,” the holding the whole story, hearing the whole story... allowing the pause. [Talking to you, Liz,] may be the most that I talk all day because most of my job—most of my life is listening.

I wish everyone could do two things: one is to do a server job at a restaurant for a few months. That’ll change your life. I was a busboy for like five months. And two, take one unit of clinical pastoral education to be chaplain—that's like four to four to six months—and that’ll change your life. I bet everybody would be a lot kinder, a lot more compassionate.

On Empathic versus Entitled Anger

J.S.: There is room for raw, unfiltered anger. For my patients, especially when they're angry about the diagnosis that led them towards that hospital room …they’re angry because they have cancer, they’re angry because of the accident, they’re angry at the disorder that just seems to be random chaos in the universe… That anger, I definitely, definitely lift up.

I would never try to persuade that person out of their honest, emotional reaction and I don't think God does either.

I gave a seminar recently on kinds of anger [and explored the question,] what makes protest anger righteous? Versus when incels or January 6 insurrectionists, why is that the wrong type of anger?

So I broke it down into entitled rage and empathic rage. Entitled, meaning high on the scale of the power dynamic, someone with majority power, someone who's been in an abusive position and has wielded that authority and still wants more—that’s entitled rage.

But empathic rage is for the community, for the people around us, and it is born out of suffering and injustice. And it is felt by those with less power and what [power] they have is taken away.

So I think it takes discerning and balance to understand. What kind of anger am I seeing?

As a culture we can smear anger all under one umbrella and we see that a lot online. People become so uncomfortable with anger that it's like, you got to be polite and we “suburbanize” our tone and, you know, we assimilate into this level of southern hospitality.

Even within the hospital when I see families grieving, there are staff that will become alarmed [by their anger]. And maybe it’s a trigger for [those staff members], but I recognize that some staff would persuade a griever out of their anger because they think it's a wrong response. They were taught that all anger is wrong.

[In that situation, I’m asking myself,] what can I do to make room for [a griever’s] anger? Even if they throw a chair, even if they punch wall. If the griever is not hurting us—the doctors and nurses [and hospital staff], that would be the line crossed—but can there be room for that type of angry grief? I 100% believe that not only can there be room, but there must be room for their anger.

LIZ: There is the distinction there of the selfishness versus communal anger that I think is so key, right? If it's really about me and getting what I want, even if it means oppressing and harming other people, then that's obviously anti-gospel and anti-Jesus. But that sense of communal rage is different.

That distinction is just so helpful for people to be able to figure out, where is this anger coming from? And if it is not communal anger, what does it mean to engage it? Because anger is a cue. We get the chance to pay attention to it and attend to the [red] flag that’s flying.

How does evangelicalism need reform?

J.S.: In church teaching and in church interactions, [evangelicalism] doesn't always account for those who are suffering and vulnerable and wounded and weary. A lot of the church teaching assumes that a person is whole and able-bodied with [abundant] resources. That preaching and teaching [has in mind] the same 100,000 American Christians. They all buy the same books and listen to the same [podcasts] and they all watch the same preachers. But it does not account for those whose lives have been disrupted by disease, by disaster, by death.

I hope that the church starts to widen its arms. We must account for all the suffering, weary, marginalized, oppressed. That should be the “status quo.”

The evangelical Christian church often does the opposite—silencing victims, pushing away and saying, “You're too sensitive” or preaching “man-up” theology. To me, that’s heartbreaking, especially in my context.

I'm always thinking about the person in the back row. What about the person in the hospital bed? If this sermon can't work for the suffering, can it work for anyone?

LIZ: …because that's who Jesus came for. He came for the sick and the weary.

J.S.: He came for somebody like me. When I think of what Christ did… he went first in all the ways that matter. Christ loved first, reached out first, humbled himself first. He set the example of not putting ourselves first in the sense that I am better, I am superior. I am at the head of the line. Rather, he went first into the deep end to let us know it's safe.

About J.S. Park

J.S. is the author of The Voices We Carry: Finding Your One True Voice in a World of Clamor and Noise.

J.S. currently serves at a 1000+ bed hospital, one of the top-ranked in the nation, and was also a chaplain for three years at one of the largest nonprofit charities for the homeless on the east coast. He’s been interviewed for his work as a chaplain on the Today show.

Follow him on his website, Instagram or Twitter.

Curious Reads

#1

Sticky state of affairs: peek inside a very fractured royal family (which seems to represent the entire British commonwealth, come to think of it…).

“‘Harry actually suggested that they use a mediator to try and sort things out, which had Charles somewhat bemused and Camilla spluttering into her tea. She told Harry it was ridiculous and that they were a family and would sort it out between themselves.’”—Vanity Fair

#2

Meet the “fifth-grade Picasso,” whose work sells for six-figures, NBD.—The New York Times

#3

Nancy Drew, thanks for everything.—Crime Reads

#4

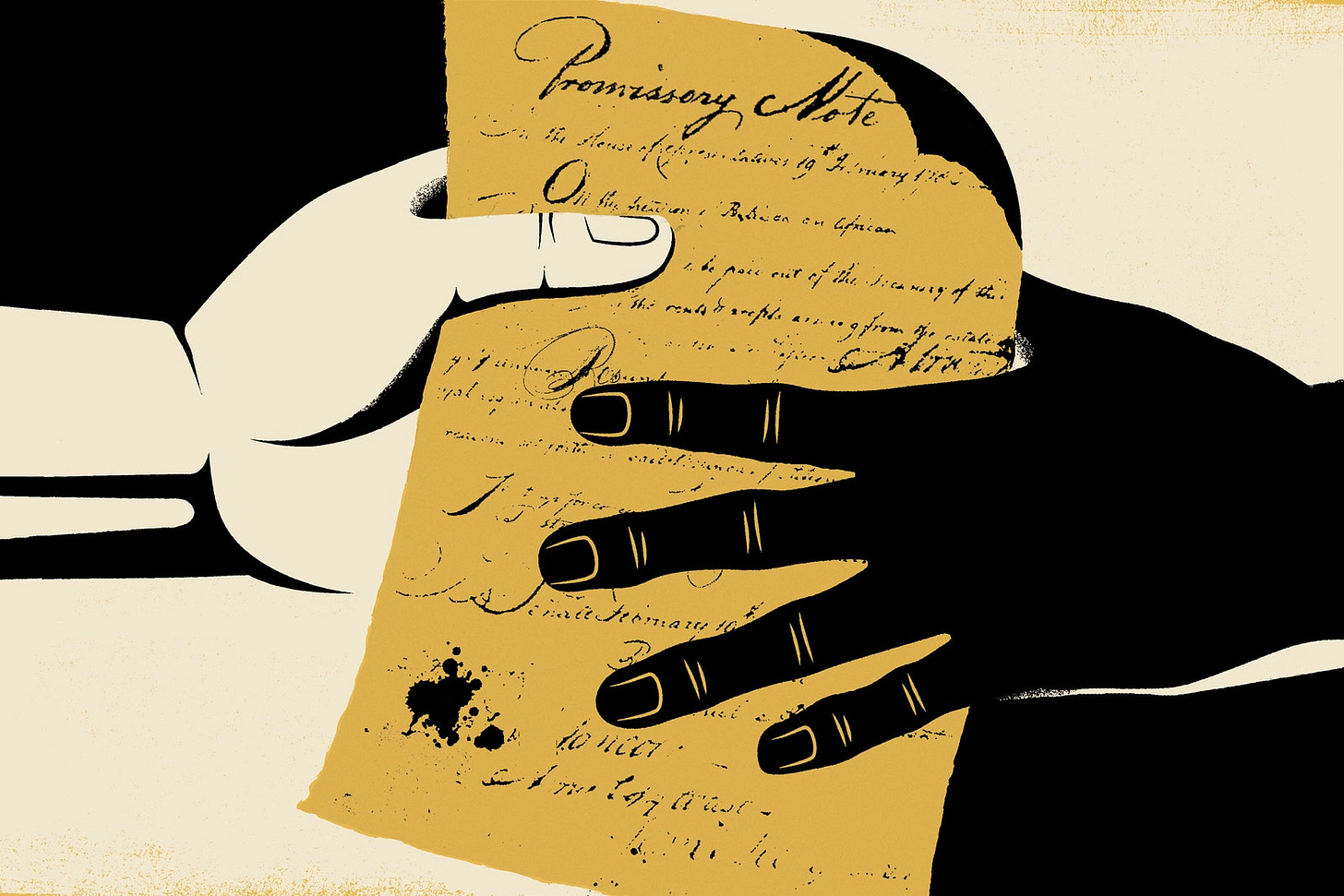

Evanston, Illinois is the first municipality to institute reparations for local black families. Here’s how it’s going. —the New Republic

#5

A hymn for those devastated by natural disasters. —Sojourners

Pray along with me, and then read this article about how disaster relief benefits the rich and makes the poor poorer. —the Guardian

Just for Fun…

Did you know Don Sr. listed Barron Trump as an exotic plant for tax purposes? JKJK this had me rolling.—the Onion

I follow J.S. Park on Instagram and have learned so much from his kind, compassion words. Such a powerful commendation for just quieting down and just listening to peoples stories

What a lovely interview!! The distinction between entitled anger and empathetic anger... spot on. Also the whole thing was great. Thanks for bringing this interview to us readers!