the Empathy List #145: Cut, Paste, and Kill Your Darlings

Revision is the real-est creative work.

Hello friend, Liz here.

Today we’re talking about the hard work of creative revision.

The 3rd episode of Knock at the Sky: A Creative Journey is live, and you can listen in your podcast app of choice.

Jeremy and I are talking about molding the final form of your artistic project: cut, paste, curate, and kill your darlings. As Queen Annie says, “The path is not the work.” (The Writing Life, Dillard)

To create art, and not just catharsis, you must curate. And the creative process provides many opportunities to do this individually—the self-edit—and in collaboration—with editors, curators, creative collaborators, and peer colleagues. But how do you decide whose voice to trust and whose to discard? Whose voice matters most? And how do you discover the true heart of the work? And how do you stay sane when your WIFE becomes the curator of your work? (We’ll tell you how that went.)

We’re also finally talking one of Liz’s favorite topics: audience! How do you keep the readers and viewers of your art in mind as you revise?

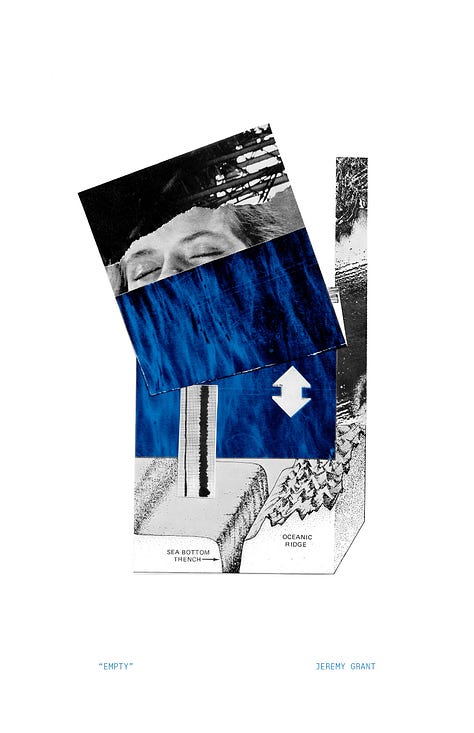

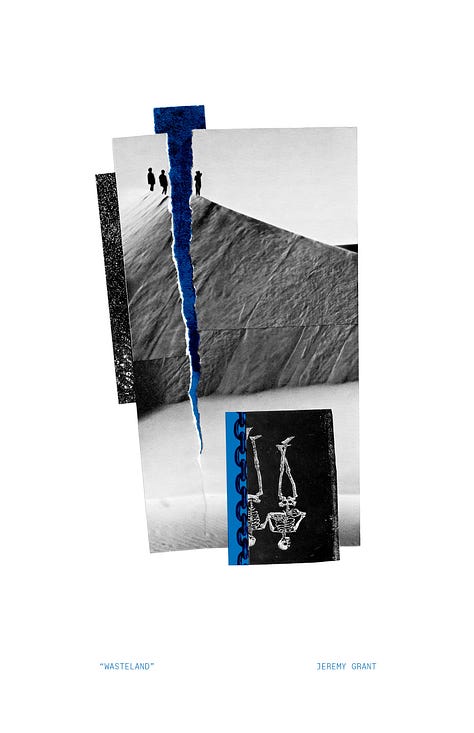

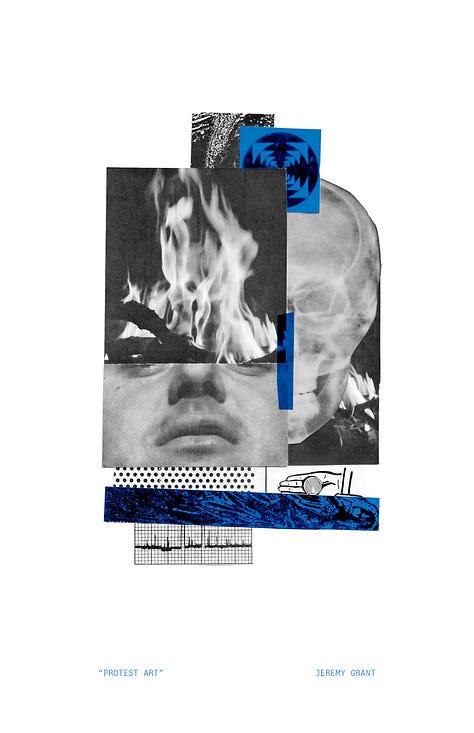

We also discuss the fine art collages that precede Chapters 7, 8, and 9 in the book that has inspired this podcast.

Subscribe and/or listen here—

Apple Podcasts / iHeart Radio / Spotify / Amazon Music and Audible / Stitcher

Below you’ll find an edited transcript of our conversation.

Thanks for reading and/or listening, my friends! Now, let’s get creating!

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

THE PODCAST—

Knock at the Sky: A Creative Journey, Episode 3: Revision

No, I Don’t Want You to Fix It, I want a Gold Star and a Hug

JEREMY: So let's dive into … the idea of feedback. Early on in our [romantic] relationship, you would sometimes bring me an edit or first draft of something you were working on, and you would show it to me, and I would be excited to …read it, and I'd bring it back to you with notes and edits, and I'd have it marked up, and I'd be like, “Oh, I really like this part right here, but what if you brought in this idea…,” etc. And [that early feedback] would immediately take the wind out of your sails? You would feel so deflated, like, UGGGGHHHHH.

LIZ: [Laughs] No, I loved that. I don't know what you're talking about…

JEREMY: It would, a lot of times it would sort of like kill the idea for you. And then I was excited about it and I was expressing that by giving you feedback and critique…

LIZ: But I actually wasn't looking for an art school critique. I was looking for a gold star. Like, hang this up on the fridge, will ya?

JEREMY: Exactly. And we had a couple rounds of that [miscommunication,] and I had to re-center [and ask myself,] okay, let me just ask [Liz], what do you want in this interaction? One of the key [questions] was, how early in the process is this? [Are] you just excited about an idea and you wanna share that excitement with me? … If so, then great. I can read it and I can hold my thoughts to myself.

LIZ: [Laughs] All those shiny bright thoughts.

JEREMY: Some general enthusiasm and encouragement went a long way in [improving our interactions]. And I could… let it be and say, you're gonna continue to evolve this obviously and edit further.

LIZ: I imagine this is like an artist couple problem. I'm like, I don't want you to fix this. Can you just gimme a hug? That’s what I want right now.

JEREMY: Some … [is just] generally applicable to relationships. … Is this a “fix-it” request or is this a “listen” request? What do you need from me in this moment? And you can't read each other's minds. You can't just … know what another person needs in a moment. And so [instead,] actually… communicating. … it's terribly unromantic and pragmatic. But it's helpful. It's helpful I think in collaborations that are not with a partner as well, to clearly express [yourself]. We hit on this… [in] the idea stage— setting some ground rules for collaboration. …

LIZ: Yeah, you've had conversations like that before with collaborative partners.

JEREMY: …If [you all] need a contract, then great, but even just… defining your mutual expectations for a project and talking about uncomfortable things. [It’s necessary] to say, what if this really takes off? Or what if it doesn't go anywhere? …who's paying for this or that? And who gets the money? For us, it's… less of a question, 'cause we share money.

LIZ: Well, because I'm getting all the money from this, so… [Laughs]

JEREMY: You're getting the money, but we have the same bank account. …that's what worked for us early on. You know, you do you, if you have separate bank accounts, whatever, we don't care. But as long as you have [clear] expectation around [money].

Who gets a say when it’s time to edit?

LIZ: What's interesting about that is the question of who gets a say early on [in a creative process]. There are different phases where you may want feedback or you may not, you may just want the pat on the back. Or you may want [only] bigger picture feedback. For example, you don't wanna hand in a draft to a developmental editor and then get feedback on your grammar. That's not the phase that you're at. And so you …need to clarify where you are in the process.

The revision process is long for books. So Jeremy and I were just cataloging all the different editors I had for this book. I had a developmental editor, I had a theological editor, I had a science fact check, I had a copy edit, I had a proofread. I mean, it goes on and on. We had a design check.

JEREMY: Well, and this book… is a… unique beast in that wa.y … You're… crossing over into a lot of different disciplines. It just required additional attention, and feedback, and critique from [experts in] different disciplines. You're writing a lot about science, so it was important to get an outside opinion to [determine], am I treating the science accurately? Am I accurately… reflecting the heart of what this research was about? And …am I saying this in a way that is correct, as well as artful? Because… at the end of the day, you're creating a work of literature. It's meant to be a piece of art. It's meant to be engaged… in this …experiential way.

LIZ: Not like a textbook.

JEREMY: …but you also want it to be factual.

LIZ: Yeah, yeah, yeah, so kind of how I read the Bible, too. [For example,] I don't expect [the Bible] to be exact, lining up with every factual understanding we have of the universe. But that's a different story.

I think what's interesting though is … defining who gets a say [in the work-in-process]. There are certain points in the process you don't actually get to decide as an author. And I … am extremely grateful for each of these editors who spent a lot of time with these words, really… picking through them and really spending time thinking through how they could be interpreted.

Jeremy and I have [also] talked about… how important it is for artists, for leaders, especially Christian leaders, to be able to admit when they're wrong. And I think … that process of … humility starts in this revision phase, when you're willing to say, I am going to take the feedback and criticism [of] these trusted voices, and I'm gonna take it seriously, and I'm gonna apply it to this work because I take the work and my audience seriously.

JEREMY: Part of that is … an act of humility towards… the truth. …Like, if I'm wrong about [my] approach [in] this… bit of science writing, and I'm working to build this bigger metaphor and to map it to… meaning, and then a science editor comes back and says, actually, you kinda missed the mark on that. You [were] not gonna forge ahead and fudge the science to make it fit your analogy. Which … is… the impetus behind the whole project.

LIZ: [Laughs] Right.

JEREMY: Genesis has been twisted to be [considered] a scientific manual, and [with it,] we can reverse-engineer the age of the earth based on these genealogies…

LIZ: …And, by the way, figure out exactly what the family is supposed to be like [from a few lines of poetry]…

JEREMY: [Laughs] …And we will forge ahead with this [goal] in the face of … actual perceived reality. I always talk about this, and this is a little bit of a tangent, but things like [defining] the age of the earth …by the time it takes light to get to Earth from distant galaxies. …The young earth creationists will say, well, God created the light in between the star and us, so that right away it was fully functioning,1 which is… a post-rationalization that makes God a trickster and says, you can't trust your senses, which I don't think is true. I think [God actually] encourages us to explore.

And I think that’s … [your] spirit here. You’re… accepting edits and revision from people who are trusted, who have expertise in their own areas.

LIZ: That discernment piece is really huge.

Jeremy Has a System for Collage Revision

LIZ: Another really big part of the revision process has to do less with… truth and facts and more with…the big picture. So, how do all the different parts work together toward the whole, and how can you kind of subtract and simplify? You could look at my writing and say, that's not very simple. That would be a fair critique. But for the sake of definition and clarity, deciding what's essential, what could be subtracted, what actually is distracting or detracting from your ultimate aim. That’s a very important part of the revision process.

Jeremy, I'm curious what that looked like for you with the art as you are… reading through my words. I know there was a revision process in your practice. Can you talk about what that looked like?

JEREMY: … In [college], I studied design and illustration, and I had professors who taught us that when you're making a painting, or when you're making a design there, …there comes a point after you have put the bulk of the work onto the page where you need to decide, is [this] done? Is there anything that I can take away from this? Is there anything I should add to this? And everything on the page is either detracting or adding.

And thinking of everything …. in that framework was helpful for me to say, I added a bunch of stuff to this collage. Half of it is muddying the story or the composition, it's actually detracting [from the whole]. And so being able to … fluidly add and subtract is important to my practice. It works with collage because, just from a craft standpoint, … I have a system…

LIZ: Always systems.

JEREMY: I have little ticky tacky pieces of tape, [and] I will lightly tape … pieces of paper together.

LIZ: Yeah, nothing is taped down initially, which is a problem with children around, by the way. That is a problem … when they're young. I mean, … one of our children did eat a collage one time as a snack. Take it apart, piece by piece… [Laughs]

JEREMY: [Laughs] lil baby….

LIZ: I know, poor bud.

[Back to the system…]

JEREMY: The way that I'll do it: I will… very lightly attach pieces of collage together so that I can see them in place, but also I can experiment with removing a piece, replacing it with a different one, trying different compositions, trying different overlapping images without layering too much… Because there is a point where you can add so many things to your composition, so many ideas or so many images that it becomes illegible. And … in some cases that's great, you know, maximalist art is its own thing. But in this case [of the Knock at the Sky book], I knew it was gonna be small. I knew it would be on [a] page. I knew it was gonna have ties to your writing…, that the printing would be black and white, just regular grade paper [and] in line with the words. And … I didn't want the art to like take over the book either. So there were parameters on … [my collages]. [So that meant] keeping it loose for a long time so I could try things.

LIZ: I admire the way you do that.

”Slash and Burn” Book Editing for the Sake of the Reader

LIZ: The editing for me, the subtracting, simplifying process… I mean, I am naturally wordy. My developmental editor will tell you this. She likes me, but she doesn't like this about me. [Laughs] I tend to need to cut about 10 to 20% of the manuscript anytime I've written a book. And this is actually not the first book I've written, just the first I've published.

Anytime I'm writing a book, I have to cut about a fifth [of the final draft] in just extra words and extra stories and things that are just generally detracting. … The number of stories I either condensed or cut out for the sake of clarity [in Knock at the Sky], you know, so we could get to the point sooner, so it would be less winding, so it would just read more clearly.. that's a huge part of my process as well.

JEREMY: Do you ever find that you need to sort of fully start over?

LIZ: Oh yeah, definitely. It's so offensive and annoying when that happens. So rude.

JEREMY: You get so far down a path and you're like, no, that's not it. I just need to… put this whole thing aside.

LIZ: [For example,] I actually had … one question that I couldn't get outta my head. The early church fathers were really obsessed with [the question of,] what was the first language? …What [language] did Adam speak? And they had this whole … winding theology about why [the first language] was ancient Hebrew. And that's not in the book. …I spent quite a bit of time thinking through that and trying to write about that. And it just was not right. I had, I had to take it out. It just did not help the book overall. And it's an interesting question, but again, it's not for this project.

God Creating and Destroying 1,000 Worlds

JEREMY: You talk about in the book this idea of God creating and destroying a thousand worlds. Is that a [Jewish] midrashic story?

LIZ: … So there's the story of God conceptualizing the earth before it was made and creating an outline of the world. And God looks at it and says, that's not quite right. In this midrash, the story goes that God did that a thousand times creating and destroying a thousand worlds before God created this one in which we live and reside.

JEREMY: Those midrashic stories, as I understand it, the purpose was … to expound upon the scriptures, the traditional stories that are… included in the Old Testament works. The midrash was meant to help you understand [the Hebrew Bible].

LIZ: Exactly. There's a sense in which Jewish midrash is an exploration of what can be said about the scriptures, not necessarily what is true or factual, or even meant by the authors or… God. It's much more about what exists in the white space, the negative space, the margins, the space between the letters, the space between the words. The Bible is an ancient work of near Eastern literature, and it is not entirely clear. I mean, no matter, you know, how many evangelical preachers try to tell you that.

I [between] the story about the pottery class [we mentioned in the last episode]. I think about that story so often— you know, the students who… were graded based on how much clay they used, how much it weighed, something like that.

JEREMY: Yeah, the class that made the most pots ended up making the best ones. The repetition of the process meant that the quality was better in the end.

LIZ: Right. And I like to think about this midrash as God… creating something in clay and [saying], you know, it's not fired yet. And God decides, no, it's not quite right. And God smashes down the clay on the wheel again, and tries again. And …in evangelical theology that can sound kind of heretical, like God changing God's mind is not okay. But I actually think what it communicates is not that. [This story, to me,] communicates God's… humility, and God's creativity, and the delight that God takes in returning over and over again to these ideas, to these people, to this creation.

JEREMY: There's an idea of like, so if a potter makes a pot that isn't perfect, was that wrong? Was that a waste of time?

LIZ: Of course it was.

JEREMY: Oh, I'm sorry. [Laughs] Well, I guess we solved it.

…The outcome doesn't always have to be the object at the end. The outcome sometimes is the process itself. That process ultimately means you make a better product in the end. But I think that's a really beautiful way of illuminating this character of God that we see in the scriptures. [This story says,] this was a Being who practiced at this and who cultivated a form of creativity before deciding this [creation] is the one.

LIZ: Well, and imagine the joy in that process. Do you know what I mean? Like a Deity who is self-contained and in perfect relationship within Theirself. The fact that this Deity still devotes so much time and attention to the creation of something outside of themselves… I think that speaks to the joy [God takes] in [God’s creative] process and the generosity [that exists] at the base of the universe.

Revising as an act of generosity (or neurosis?)

LIZ: One of the things I've come to understand as a writer is that the whole point is actually revision. Like the first draft is not what matters. What matters is what comes as you spend time with those same words, refining them.

“And for me, the act of revision is an act of generosity to my reader.”

…To say, how can I make this [sentence] more comprehensible, more interesting, easier to read? …How do I not bore them to tears?

JEREMY: You're not getting paid by the word here. You're not just piling on more and more. There's an editing down that is in service of your reader. I think it's also in service of the work. It's probably both. You and I have had discussions about this in the past. You can get stuck in a trap of thinking too much about what your audience is going to think...

LIZ: That’s me in particular, he means, I can do that.

JEREMY: Well, we all can do this. I mean, you think about how is this gonna look on Instagram when I post this painting, or this collage, or whatever? Will it present well? Will it get likes? Will people be into it? Will it sell? [Anyone] can get caught in a trap of only thinking about your audience.

The Artist Alone in His Studio and Self-Curation

JEREMY: On the other side of the spectrum, you can get caught in self-indulgence.

LIZ: ..as if [making this art] is entirely about artist catharsis. “Whatever I want [my art] to be as the [priority] that matters most.”

JEREMY: And I mean, I personally tend to lean more toward that side, where I'm like, who cares what the audience thinks? I'm gonna follow this artistic vision.

But there is also a, a danger in that. [For example,] am I saying anything at all?

JEREMY: Curation is a big part of the artistic practice, … in any discipline really. You are the first arbiter of taste in your own work.

LIZ: The fact that you created it, in other words, is not quite enough. You kind of need to have more. You have to decide, this is the thing that I actually want to put into the world. That's different than, I'm just creating for myself. So there's a broader vision there, a universality that you're aiming for. Why would this mean something to somebody else? And would I feel proud to put this in particular into the world?

…

JEREMY: And…I also have expectations of my own work where I'm gonna curate something to my own standards. And some of that is, as I've already mentioned, around spontaneity and having collages that still feel like they were easy to put together. Like, there's some big pieces in here, and there's like an airiness to the composition. So [creating] this balance of, it's meaningful, it's also spontaneous. It mirrors the work that it's responding to, this collaged essay style where some [sections] are stories, and some are metaphors, and some are engaging with this old text.

But [as an artist,] you [do] need a time where you're creating free from the considerations of audience. [And] you also need somebody to come to a studio, visit a curator, a fellow artist,…

LIZ: Your wife…

JEREMY: Your wife… [Laughs] … to come look at what you've been working on and say, “Hm, this makes me think of this. I'm reminded of this work of art by this [artist]. This makes me feel something. I don't feel anything when I look at this.” You need that feedback, … you need that critique in order to make something that has a life of its own beyond your studio.

LIZ: Yeah, [like] there's some sort of universality to [the work].

That time when Liz played curator in Jeremy’s studio… and how it went. ;-)

LIZ: Speaking of [curation by your wife], I would be interested to hear [more] about that. There was a point of this [collaborative] process where Jeremy laid out the whole spectrum of collages—all 11, one for each chapter. He laid them out for me to look at, and we …tried to figure out [which collages were] fitting and [which weren’t]. Can you describe that process, Jeremy? And what did it feel like for you?

JEREMY: I think anytime you show your work to someone else, it can feel vulnerable. You [Liz] often felt that way. I think especially early on in our relationship showing me your work felt tender…

LIZ: …that was probably 'cause I knew [my writing] wasn't that good at that point, you know what I mean? Like, you try and, you know it's not quite there, and you want it to be, you have the vision in your head. [But you can’t reach it.] Anyway, that was my early creative life.

JEREMY: On the design side, I've often presented concept work to people and tried to frame it to them as, look at this next page with the eyes of potential. I know, and you know, this is a rough first draft, but let's dream together about what it can become…

LIZ: Vision casting.

JEREMY: And on the fine art side and in this project, [it was] a little different than a design setting. Still a tinge of that kind of client artist relationship here, where you're leading the way with your work, and I'm following along to support with art, but yeah, [it was] vulnerable.

…the stage that I'm thinking of, I had a really solid pass at each of the pieces. [They were mostly done.] I laid everything out, and I didn't want to lead you too much. It was gonna be more valuable to me in the end to have a gut reaction from you. So even though I wanted to contextualize, and like sell [my work] to you…, I was like, let me just lay 'em out, and you walk through. I had them labeled—this is chapter one, two, through 11. …And you took your time with [each collage]. You were a thoughtful participant in feedback and critique.

And there were maybe three or four that you kind of pointed out, [and said,] these ones aren't really resonating with me. I get these other ones, even if I don't understand everything about them, I can feel this energy. …This goes with what I'm writing about.

LIZ: Right. There's like mood, or there's interest, something pulling me into those.

JEREMY: They're getting your attention. You feel like they're communicating something meaningful, and you would spend more time with those. And then there were a few [about which you said,] I'm not really feeling this. At that point, I took some time to say, here's one or two things that I would fight for. I really do want a skull in this piece about protest art. [Laughs]

LIZ: We're gonna talk about that one today. That's a creepy one.

JEREMY: I do wanna have some of this more edgy imagery. Or this piece is meaningful to me because… It might just look like a texture, but it's actually sand that's been turned into glass by heat or something. And it had like this kind of meaning where, like in the collage, you may just view it as a texture. You may experience it as a texture, but it does have deeper meaning. So there were one or two pieces that I was like, I do wanna incorporate this image somehow, but I also don't need to be precious about these. And I can create two or three more collages for this chapter and see which one “wins.” That’s an exercise both in the feedback and the critique, and it's an exercise in curation.

…

LIZ: I want to [talk about] one more thing about that curation process. …There were a couple of [collages where I saw them and said,] I really do not resonate with these. Could you make another one? Obviously that's a hard ask, right?

But there also were a few where I would say, I'm noticing this theme in these collages. So these faces are recurring, and as I'm looking at them spread out, I'm noticing that there's kind of a gap in this section. Could you add a face in one of these?

Some was compositional critique, like, I’m noticing that these ones are really square, these ones are loose shapes, could you spread it out a little bit more and do some more work on form with some of these, change up some of the compositions? Would you consider that?

That was also part of the process—looking at the whole scale and saying, okay, what would these look like on a wall? You know, from the beginning we were like, maybe we'll sell prints of these, wouldn't that be fun to have these as prints, or even do a show with these? Jeremy [does] show his work in galleries. So, that was always a consideration.

And that was part of what we were considering, too, the whole range of them, not just as individual parts, but as a series, how do these work together?

JEREMY: Yeah, and they should have some dialogue back and forth. I think I mentioned in our last discussion [that] some of the meaning that I was working into these around the torn paper, the metaphoric quality of that. [The torn paper] feels like lightning when it's on the page. It also has this meaning-making you can build around it [to represent] divine intervention.

LIZ: A nod to transcendence.

JEREMY: So those kind of things? Super helpful to identify. It’s easy as a creative to get lost in your own work. You're staring at the same thing for so long that you sort of gloss over parts of it and you need fresh eyes sometimes. And I would say, in this instance, we were both invested in the success and the quality of the project to a high degree. If anybody's listening to this and thinking, I don't know how that would go if somebody told me they didn't like three works that they commissioned out of 12, and should I just make endless revisions?

No, you need to define your own parameters and have a contract or an expectation [around]… what a revision process will look like. Here's when you get to speak into the work and not…

LIZ: And to be clear, I think Jeremy was pretty annoyed at me.

JEREMY: [Laughs] I wasn't that annoyed. I mean, a little annoyed. I think, I think

LIZ: You handled it well.

JEREMY: We had an expectation going into it: we both want to collaborate. We both want to make this the best it can be.

LIZ: Or at least the best we can make it.

JEREMY: And I think we did that.

I hope you will join us for our last episode in this series, episode four where we'll be discussing release—that is, the moment when you finally have to let go and let the work wander in the wide world without you there to hold its hand season.

About Jeremy and Liz

About the Author

Liz Charlotte Grant is an award-winning essayist whose work has been published in The Revealer, Sojourners, Brevity, The Christian Century, Christianity Today, Hippocampus, Religion News Service, US Catholic, National Catholic Review, The Huffington Post, and elsewhere. Her essays have twice won a Jacques Maritain Nonfiction Prize. She also writes The Empathy List, a popular substack that has been recognized by the Webby Awards (‘22, ‘23) and the Associated Church Press Awards (‘23). Knock at the Sky is her first book.

About the Artist

Jeremy Grant is a multi-disciplinary artist whose work is rooted in contrasting modes of natural and mystical experience through a practice that bridges association and obfuscation. He has exhibited work regionally in Colorado since 2008. His 2019 film “Remnants” was exhibited at the Supernova Film Fest, and the Denver Film Festival. He holds degrees in Graphic Design and Illustration (John Brown University, 2007).

[American, b.1985, Monterey Park, CA, USA, based in Denver, CO, USA.]

Here Jeremy is referring to an argument that says, yes, light takes millions of years to reach us. However, the light we see in the sky from stars light years away cannot have taken millions of years to reach us because our universe is not millions of years old, according to the Genesis account. Therefore, the young Earth creationists suggest that when God created the universe, God must have created the source of the light millions of miles away and the path of that light, too, which explains why we on Earth can see this light from such a great distance right now, despite their assumption that the Earth is too young for light that far away to be seen by us, based on the speed of light. This post-rationalization helps reckon with the discrepancy between the time it takes light to travel and the young Earth timelines young Earth creationists have drawn out of the pages of Genesis according to a literalist reading.

This was so timely for me. Thank you!