Curious Reads: Parents, Stop Oversharing About Your Kids Online

The first generation of social media babies are taking down their influencer parents.

Hello friend, Liz here.

#1 Today’s top of the fold story is a debate about privacy—that is, the first kids of social media influencers are all grown up. And now they’re lobbying for states to provide protections from their parents’ oversharing.

This story made me uncomfortable and sad and doubtful of my own past history with social media (what will my kids make of what I’ve shared about them?). And that’s why it’s a perfect read to provoke deep thinking this afternoon!

Read “The first social media babies are adults now. Some are pushing for laws to protect kids from their parents’ oversharing” by Faith Karimi at CNN

The Highlights

How would it feel to have your parents splash news of your first menstrual cycle across Facebook? Cam Barrett found out first-hand.

“I was in fourth grade. I was 9 years old. The date was September 9, 2009. And my mom posted … something like, ‘Oh my God, my baby girl’s a woman today. She got her first period,’” Barrett said. “A lot of my friends and their parents had social media, so it was super embarrassing.”

Her mother was a popular influencer on MySpace (remember when?) and Facebook, and earned celebrity perks. But her no-holds-barred posting meant that her daughter did not feel safe at home—tantrums, medical diagnoses, and the fact of her adoption all ended up on the internet as fodder for middle school bullies.

“Sometimes, she hid in her room to avoid appearing on camera. She didn’t confide in adults during her teenage years because she feared her secrets would end up on social media, she said.”

Her mental health declined, and she no longer goes by her legal name in order to obscure her digital footprint.

Barrett is not the only kid to have their private life on public view. Child actors have long experienced a similar phenomenon. Yet social media does not allow work-life boundaries, meaning that the kids of influencers feel as if they’re constantly performing, even at home. No space or event is truly private, leading them to feel as if they are constantly on display. And, really, they are.

“Some children of family vloggers are living in homes that feel like sets and with parents who double as their bosses…” writes Karimi. “‘It’s like living in a movie set all day, every day,’” says Chris McCarty.

McCarty continues:

“A lot of people who follow family channels and kid accounts have never zoomed out and asked themselves why they have such intimate access to a kid they’ve never met,” Easom said. “I want people to remember the curated videos (that) family channels are putting out do not necessarily represent what happens when the cameras are off.

“Imagine a family vlog where instead of antics, intimate details such as mental health issues, grades and personal things like potty training and first periods get shared online, where they live forever. Parents then use this clip as clickbait to generate intrigue and revenue for a monetized family channel.

Now, kids like Cam Barrett, Caroline Easom, and Chris McCarty are asking lawmakers to pass laws to protect kids like them. And, they want to be paid for their work, asking for both financial compensation for children whose private lives go online without their consent, and a right to delete unwanted content that exists on their parents’ accounts when they become adults. They want to control their digital footprint, to take back their privacy, and to fight for the rights of other children subjected to the same.

Currently, legislatures in New York, New Jersey, Washington State, Maryland, California, Georgia, Missouri, Ohio, Minnesota, and Arizona are considering new child labor laws designed to safeguard child influencers based on a European standard called “In some states, proposed legislation would include a clause that borrows from a European legal doctrine known as the “right to be forgotten.” The first law to pass, in Illinois, goes into effect this July due in part to Barrett’s advocacy.

Reflection: Is the family vlog dead?

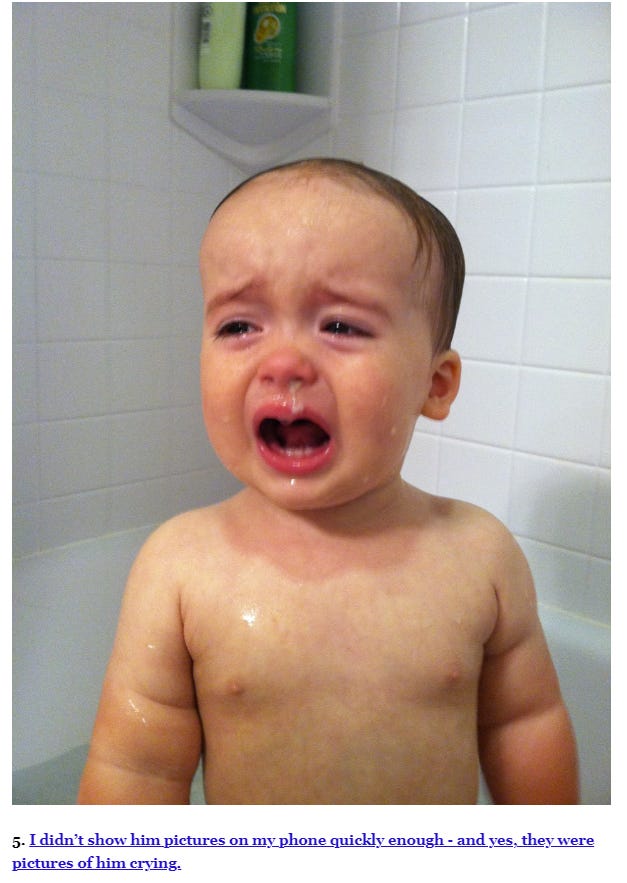

As an adult who came of age as social media took off, I can very much relate to the parents in these stories. Remember the tumblr “Reasons My Son is Crying”? Where the mom of a toddler stuck her phone in her kid’s face while he was tantruming and documented the reason for his tantrum?

…what could go wrong? ;-)

But also, have you seen these photos? They’re genuinely HILARIOUS. If you’re a parent of a toddler, tracking the speech or even fits of your kid is second-nature. Snapping a photo and writing a snarky caption is a way to maintain sanity, to connect with the adult world that feels so, so distant when you’re in the midst of the vortex of Big Toddler Feelings.™

I had my own children in 2012 and 2014 and began snapping photos that I posted to an instagram account, sharing mostly with out-of-state family and friends. (No one else cared, frankly, and I never made a cent off of my Gerber babies’ pinch-able cheeks.)

What I mean is, the rise of family vlogging felt natural and fun—at the time.

But there was another side to the industry, as this Cosmo essay about “sharenting” (sharing + parenting) reveals:

Vanessa1, [one child participating in the family vlog business], says, “There was this idea that you have to look perfect and pretty and like nothing is wrong all the time in front of the camera, and if it seemed like I wasn’t trying hard enough to maintain that image, like my smile wasn’t as bright as it should be or I didn’t say a line with enough enthusiasm…that would usually devolve into accusing me of not caring about our family. I was told by my mom, ‘Do you want us to starve? Do you want us to not be able to make our payment next month on the mortgage?’”

And, apparently, corporations seem to prefer sponsoring these family vloggers only when they engage their kids in the content—Grant Khanbalinov, 33, says his family vlog used to attract lucrative brand deals until he decided to take his kids offline. Without the kids, deals dried up.

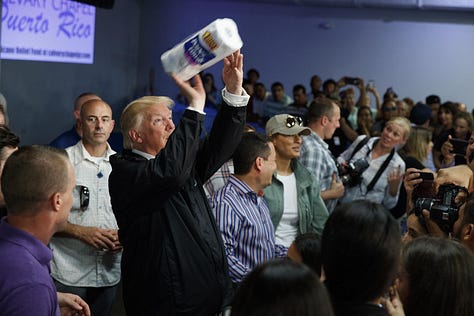

Because, let’s be honest, the economics of a cute kid holding a roll of paper towels does not equal a middle-aged dad doing the same, no matter how close the resemblance to a JCrew model.

By the way, Cosmopolitan’s series on Sharenting is fantastic. Read if you want to go deeper into the world of oversharing family vloggers.

Americans, in general, support the right to be forgotten online, according to a 2020 Pew survey. We want our private information to stay private.

But parents do not always consider the consequences of sharing our kids’ images online though—and not because we’re malevolent, necessarily, but because we’re naive and ignorant, and because we ourselves have made peace with a level of oversharing past generations did not indulge.

Yet with the scary advances in AI and the recent backlash of kids against their influencer parents, I suddenly find myself concerned on behalf of Gen Z and Gen Alpha, the generation my kids belong to. For the first time, I’m considering deleting what I have for years considered the family album of my early Instagram posts. Their safety and wellbeing is simply more important than maintaining a winsome record.

I’ve already stopped using my kids’ names online because I don’t want them associated with me or any of the writing I do. I also use online privacy software to try to keep trolls from doxing me and my family members (which happens when you write about controversial topics, as I do).

But I’ve started considering scrubbing my accounts of any photos of my kids and severely limiting any photos I post of them. Like mom Hannah Nwoko in the UK, I’ve found myself asking:

“Why am I sharing? Who are these photos for? And more importantly, who could they be reaching?”

It’s humbling, as parents, to realize we have messed up. But it’s inevitable that we will harm our kids. It’s worth examining our online habits to determine the reasons we have brought our kids into our internet spaces. Regular introspection—and possible behavior change—is necessary and good.

Of course, I realize that every family is different. Posting cute quotes or family photos is distinctly different than sharing intimate body details about your kids. And some kids may tell you their parents that they enjoy a version of online exposure. (My daughter has asked repeatedly for us to help her start a YouTube channel… and that’s an easy no for these parents. ;-) We tell her that the internet is like a neighborhood and she’s not ready to walk around on her own without us yet.)

The real question is, how will we parents respond once we realize we’ve harmed our kids (even unintentionally)? Will we take responsibility and action to repair? Or will we pretend everything’s okay, despite evidence to the contrary? Will we believe our children when they tell us they’re not okay?

For myself, as a memoirist, the question is even stickier. What level of exposure will I allow within my writing? And how will I temper the instinct to tell stories about my life while keeping the privacy of my children in mind?

You can see how this is a tricky question.

For myself, I’ve drawn a line: I will not reveal anything about my kids that could expose them to outside harm. I will honor and protect them. That’s my job and privilege as their mom. They matter more than any platform-building or book deal. They matter more than success in my work or even than paying my bills. Put simply, they matter the most. And I want them to grow-up believing it.

Thanks for reading. Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

Tell Me: How do you resolve this question as a parent? Do your kids show up in your online spaces? Why or why not? What conversations are you having with your own kids about being on the internet? What boundaries have you drawn?

More Curious Reads

#2 Former President Trump was convicted of all counts in his “hush money” trial, making him a felon. And he’s mad as hell about it. (So are his followers.) —NPR

But does a “guilty verdict” really matter? Here’s the case against the natural cynicism that will follow this verdict. —“When people stand up to Trump, they deserve our solidarity, not our cynicism” by Everything Is Horrible on substack

#3 The first millennial saint is about to be Italian teenager Carlo Acutis. He’s known as “God’s influencer.” —The New York Times

#4 A Jim Henson documentary has just dropped on Disney+, but you should watch this YouTube doc instead for a truer portrait. —Slate

#5 Breakdancing is an Olympic sport now. Read an interview with the Canadian who’s likely to take the gold medal. —Wired Magazine

Who needs child labor laws? 🥶

One of the advocates against “sharenting” makes behind-the-scenes satires… and they’re chilling/funny-ish?

Her name was changed for the article.

Liz, I have so many conflicting feelings about this. On one hand, the AI stuff in particular and generally erring on the side of caution has me keeping photos off the internet for the most part. There's so much about social media we are still working through and there are definitely posts of mine I think are totally normal that could be studied in 50 years as truly bizarre artifacts of media history. I'm mostly in agreement with your essay and thankful for the research and thought you put into it!

On the other hand, I have always found it bizarre for any of us to claim "ownership" of "our" individual story. Parents and kids share a story, and I think most people are pretty sensitive to the increasing divergence of identities and narratives at least by the time kids are tweens. Blogging has changed conversations around parenting so much - I'm not sure we Millennials can really appreciate what it was like for parents to feel so isolated and not have these ways to connect, tell stories, or work through things.

Some things feel to me like common sense (ask your 9 year old if they want to share about their period??!!) but others feel a little extreme. I grew up hearing so much about my male pastor's kids and male Christian authors' kids. Is this just another way we're making up to criticize (90% of the time) moms?

Such an important conversation. I have had an older friend (he's 70 now) tell me I share too much about myself online and then once too much about my kids when I talked about their neurodivergence on a private post. But overall I'm pretty careful especially when I think about how I know so much about some of my friends' kids.

Things really got interesting with our viral video this winter. People on TT and IG were MEAN. My husband and I spent hours blocking people until I eventually gave up after a few weeks. My kids have been told for years that if they are ever on social media they should not read the comments and they rolled their eyes when I said the comment section was bad. But that's not even what you are talking about. Social media has had a harmful effect on teens mental health and probably adults' too. I think we all could use some time to reflect on this more. And yeah, I think one kid would be embarrassed over a crying picture. But the other could see the humor in it.