Curious Reads: Making Fun of the President

Displaced Chinese nationals reflect on Jimmy Kimmel's free speech woes.

Hello friend, Liz here.

#1 This week’s Top of the Fold is the story of a cultural revolution—

That is, Chinese immigrants reflect on how American culture increasingly mirrors the authoritarian “cultural revolution” of China, including the curtailing of humorists, à la Jimmy Kimmel and Stephen Colbert.

Read these two companion pieces at the New York Times—

“Many Chinese See a Cultural Revolution in America” by journalist Li Yuan

People in China are expressing alarm at what looks like a familiar authoritarian turn in the United States, their longtime role model for democracy.

“How to Silence Dissent, Bit by Bit Until Fear Takes Over” by Li Yuan

In China, journalism and public debate were opening up, and then a leader took over and used a series of steps to dictate speech.

The Highlights

This Trump term feels different for Chinese immigrants in the United States.

Having long been a paragon of democratic free speech and political and artistic expression, the U.S. has begun to mirror the Chinese cultural revolution, also known as “the decade of turmoil.”

“Coming from an authoritarian state, we know that dictatorship is not just a system — it is, at its core, the pursuit of power,” Wang Jian, a journalist, wrote in an X post criticizing Mr. Trump. “We also know that the Cultural Revolution was about dismantling institutions to expand control.”

Even Chinese citizens have noticed the shift. On Weibo, beneath a post by the U.S. Embassy in China, one comment read, “Beacon of democracy, 1776-2025.” This account used to act like a bulletin board for Chinese citizens to see America apart from the Chinese government’s propagandistic lens. Now?

“Most striking is the language government agencies have used in social media postings. The tone, people say, sounds like Chinese Communist Party propaganda,” says one scholar.

The Chinese people have begun to identify the symptoms of cultural revolution: sycophantic underlings who fawn over a dictatorial leader, entrepreneurs vying for governmental favors, and “intimidation of the media.”

On that note, we turn to Jimmy Kimmel.

In early March, [journalist Li Yuan] asked a lawyer, a naturalized citizen living in Texas, whether he shared the unease among Chinese immigrants that American politics under President Trump was beginning to echo the China we left behind…

He shrugged. As long as late-night talk show hosts can still make fun of the president, he said, American democracy is safe.

For those of us who grew up under strict censorship, late-night comedy always felt like an emblem of American freedom. The idea that millions of Americans could go to bed each night having watched their presidents mocked felt almost magical, something unimaginable where we came from.

Because dictators do not laugh at themselves, and they do not allow anyone else to laugh at them, either. Dictators rule by fear, and laughter defeats fear.

So when ABC suspended Jimmy Kimmel’s show after Trump’s FCC signaled Kimmel’s cold open monologue criticizing Charlie Kirk would not fly, immigrants who fled China’s stifling media environment began to worry.

The 10-year Chinese Cultural Revolution of the 1960s to 1970s made the traditional, the intellectual, and the artistic suspect. Any norms, institutions, and religions had to be purged as an act of loyalty to Mao and the proletariat/communist aims. Former party leaders were mistrusted and sometimes killed. Cultural sites were destroyed by mobs. Essentially, Mao’s cultural revolution stood for populist mob rule, bringing about the downfall of any and every institution for the sake of rebuilding society so that the poor could ascend and the wealthy and influential, descend. (The topic is SO COMPLEX, so I’ll leave you to discover more on your own.)

Yet contemporary China holds even more parallels to this moment in American history. Chinese censorship and anti-intellectual/anti-institutionalism began with the Cultural Revolution, but by the 1990s and 2000s, Chinese society held space for expression and opinion. Though dissenters could still face jail time in the 1990s and 2000s, Li Yuan writes, free speech itself had not been outlawed.

However, Mr. Xi changed that. Within a few years of Mr. Xi’s takeover of the government in 2012, “Investigative reporters became extinct.” Those who delivered bad news—including bad news (even negative facts and statistics) about the Chinese economy—faced retribution.

He muzzled a newspaper’s editorial, elevated the role of a government official to control the internet and declared that all media must “love, protect and serve the Communist Party.”

Strikes, protests, and displays of solidarity echoed across China, yet Xi’s government arrested, penalized, and prohibited the resisters. The internet became a self-aggrandizing tool of the government, rather than a raucous place of debate and opinion, representing the fear within China that led to its current mode of public silence and propaganda.

Yet societal silence has a cost.

And one consequence of this “muzzle” was the COVID-19 pandemic.

When an unknown pneumonia surfaced in Wuhan near the end of 2019, Dr. Li Wenliang tried to warn colleagues and friends. He was reprimanded for “spreading rumors.”

Because no bad news allowed. As a result, the news of the virus was squashed, and the public health response was slow. And the virus was not contained. Silence led to illness led to death. We ourselves, Americans living halfway around the world, hold the record of that silence within our bodies.

Dr. Li himself perished. However, he left us with one haunting message: “A healthy society should not have only one voice.”

Reflection

This one quote from these articles will stick with me for a long time:

“Free speech rarely vanishes in a single blow. It erodes until silence feels normal.”

Censorship is nothing new in America, and certainly it’s nothing new within the white American evangelical subculture in which I grew up. As I’ve written before, I did not read the Harry Potter series until my mid-twenties, after the birth of my first child, because my upbringing barred me from “witchcraft” in every expression, no matter how mild. (See this essay I wrote about Harry Potter and Fundamentalism.)

The 1960s featured public hearings of American political censorship in the form of McCarthyism, in which accusations of communist tendencies led to removals, blacklists, and public shunning. The “Red Scare” in the U.S., despite its focus on liberals as the baddies, rather than the conservative-leaning traditionalists and bourgeoise in China, did not feel so different from the cultural revolution.

…Minus the violence!! The Red Guard was brutal.

Which, of course, illustrates an important difference between China and the U.S.: we are different culturally, politically, economically. Our governments run distinctly, and so do our politics, our justice system, our press. I am not, by any means, saying that we are the same.

And yet, I implore us to consider the lean of America toward censorship.

If we cannot disagree—if we cannot disagree loudly, if we cannot disagree humorously, if we cannot make fun of the president without consequences—what does that say about our democracy?

What does it portend for the future months with a president who has threatened a run for a third term? What does it tell us about the race for cultural power in our nation, and what have we already learned about the fragility of institutions? (Especially media institutions!)

I keep reminding myself that we are only nine months into a four-year term. That fact chills me.

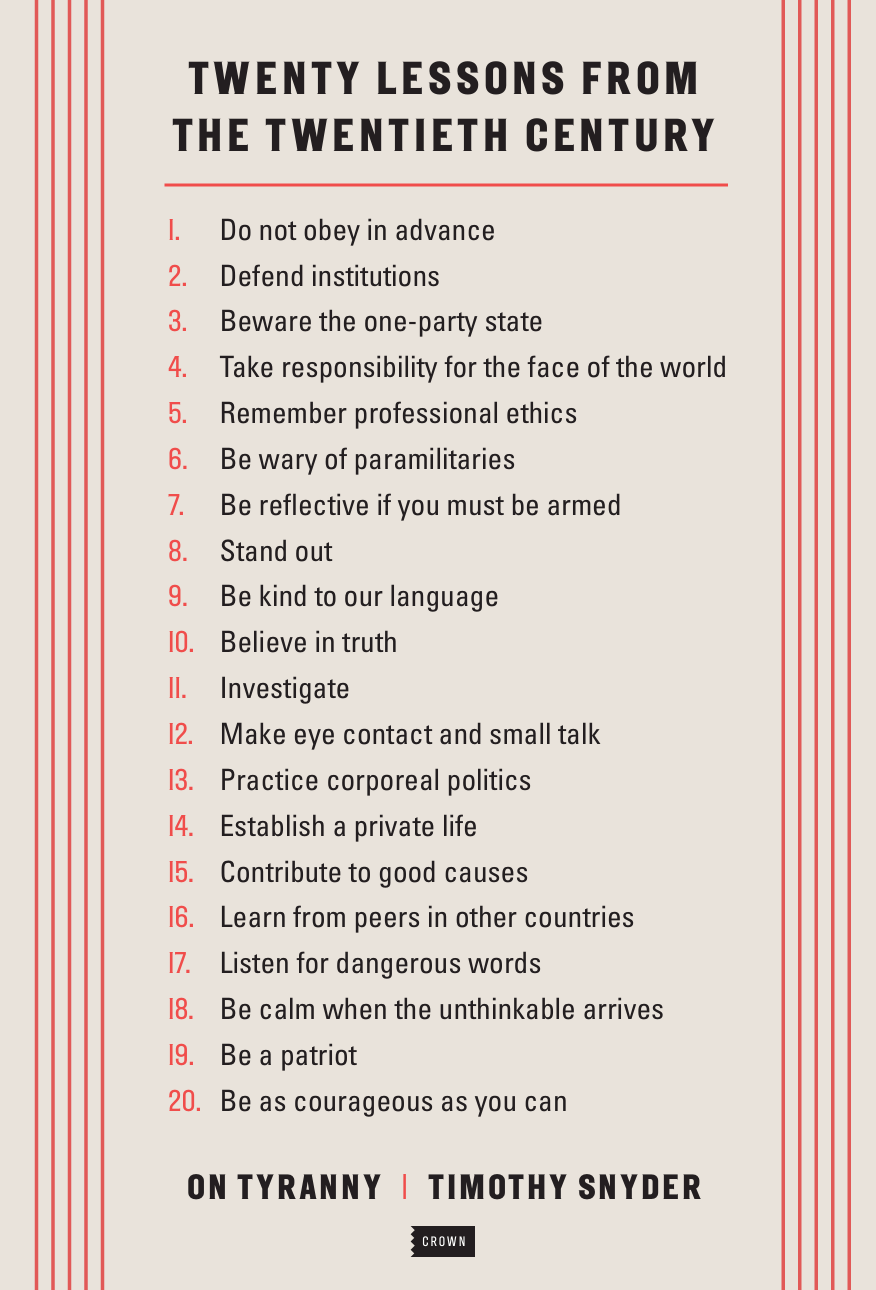

I find Timothy Snyder’s book, On Tyranny, instructive. These are his “rules” for resisting authoritarianism:

I would urge us toward the first bullet: DO NOT OBEY IN ADVANCE.

That resistance likely requires backbone and money. But I suspect that resistance will maintain our independence.

As Stephen Colbert said elsewhere, ABC’s move to so quickly suspend Kimmel represented a move of “blatant censorship.” He explained, “With an autocrat, you cannot give an inch. If ABC thinks that this is going to satisfy the regime, they are woefully naive. And clearly they’ve never read the children’s book If You Give a Mouse a Kimmel.”

I hope that we can continue to say “no” to the demand of bending to the will of the ruler. That’s how we’ll make it to the next election, my friends.

Thanks for reading.

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

More Curious Reads

#2 Soooo the rapture didn’t happen today, even though evangelical tiktokkers really wanted it to happen today. (Who can blame them?!)—Mashable

#3 I know you, like me, must surely love weird science facts. So how about a walk through the worlds of butt breathing, a tar-like goo that turned out to be a new lifeform, and Victorian picnickers poisoned by ice cream? —Popular Science

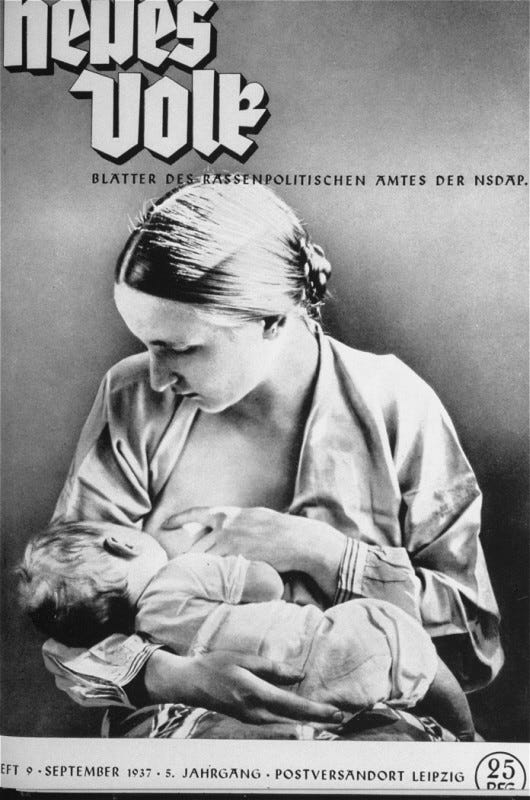

#4 Most of the good white Christian women of Germany did not resist Nazism. And D.L. Mayfield’s 2021 essay examining their acceptance of Hitler is worth re-reading. —The Christian Century

#5 A short story about a honeymoon interrupted by a first encounter.—Electric Literature

This story is part of a larger novel about “an unnamed Archivist—transgender, nonbinary—begins researching Barney and Betty Hill, an interracial couple from New Hampshire who experienced the first widely publicized event of alien abduction in the 1960s.” And it hooked me.

Just for the Fun of Making Fun…

This nonfactual article brought to you by the Onion. (These writers are doing the Lord’s work.)