the Empathy List #112: All Saints

Witnessing Death and the Church's Day for Remembering the Dead

Hello friend, Liz here.

Because I am a Big Feeling enneagram 4, All Saints Day has always been one of my favorite church holidays ever since I learned of its existence in college. (Before that, church meant happy-clappy Big Box Store consumer non-demoninationalism…and we made no space for the sad Christian days).

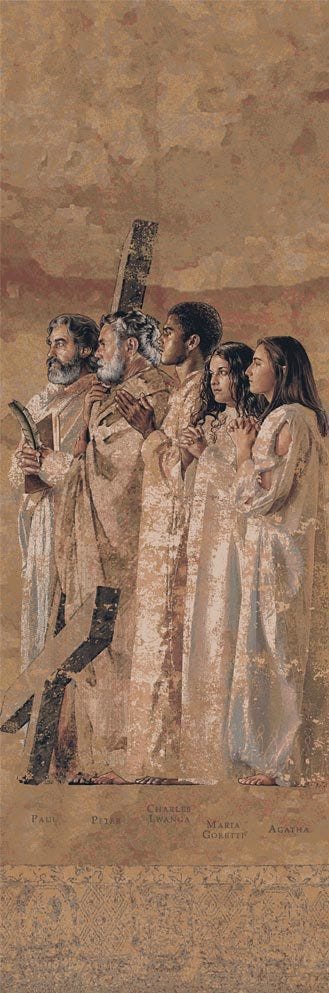

All Saints Day comes the day after Halloween—traditionally, termed All Hallows’ Eve—and the church marked November 1 as a time to remember the holy ones who have died.

How often do we, white Western Christians in particular, celebrate the dead together? Grief normally happens alone. But this is not the Christian way.

2 Corinthians 1:3-4 sums it up: “Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of compassion and the God of all comfort, who comforts us in all our troubles, so that we can comfort those in any trouble with the comfort we ourselves receive from God.” (NIV)

We Christians feel pain, experience God’s comfort, and then turn to comfort those around us. We mourn communally, bearing each other’s emotional and physical burdens. We serve, attend, wash dishes, bring Tupperwares of soup, and uphold those in sorrow because Christ first spent himself for us.

In gratitude, we pass on the mercy of God to our fellow sufferers.

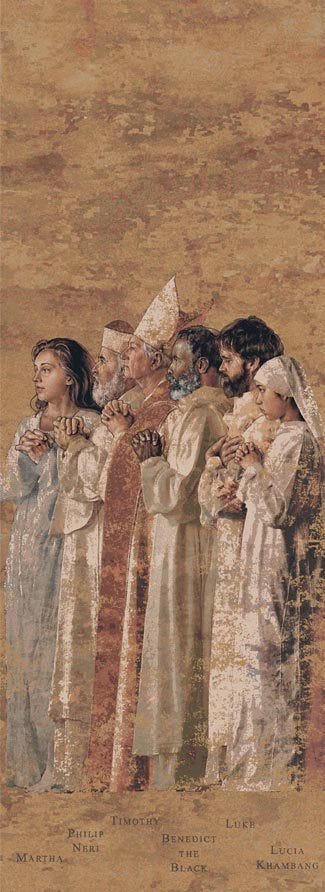

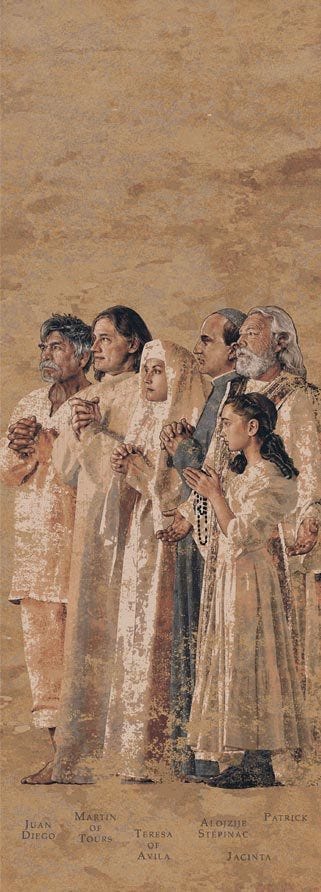

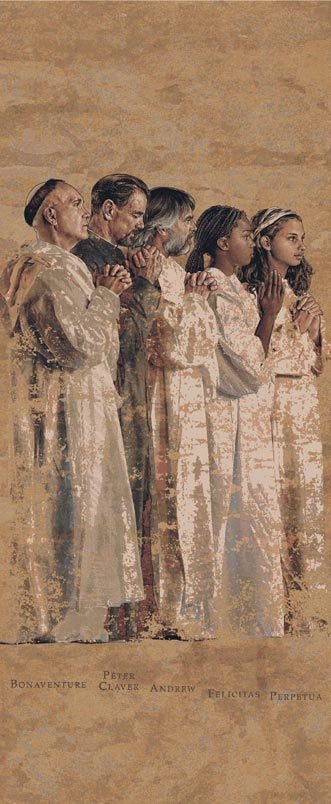

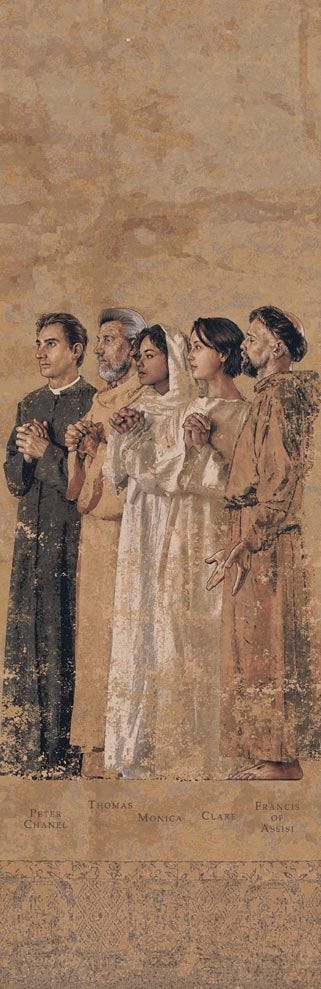

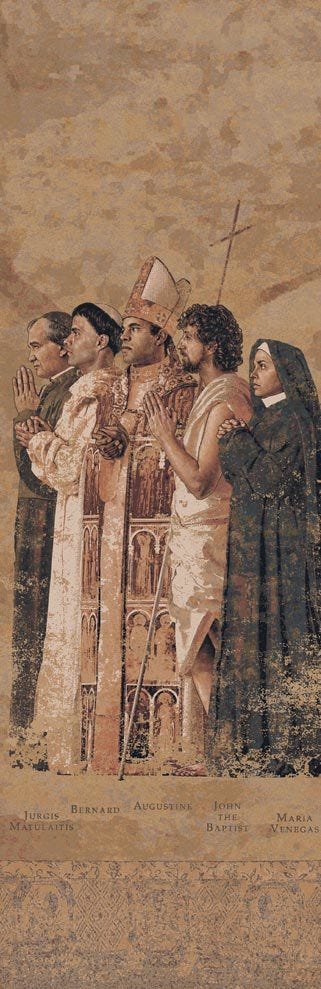

This includes remembering the dead—both our own beloved passed-ons and the passed-ons of others. Because up there in the heavenlies, I believe that a whole crowd of on-lookers cheer us followers on this very second. These are the heroes of Hebrews 11, described as "the great cloud of witnesses” (Heb. 12:1, NIV) of whom the world was not worthy.

Sometimes, when I feel deeply alone, I remember the people I know who make up that crowd—my Meema, the grandfather I never met who attended the Baptist youth group, great grandma Elizabeth (after whom I was named), Isabel Crawford, the apostles, the prophets, the children who never made it out of the womb alive. So many sweet souls who, I pray, live in the presence of God this very second, filled up with all the goodness a good God can offer, having heard the words, “Well done.” And it lends me steadfastness and courage to keep spending my life for the cause, as they did to the end.

Discussion: Who do you know in God’s “great cloud of witnesses”? How do you celebrate those you’ve lost, both alone and in community?

As you know, for the next couple of weeks, I’ve been furiously editing my in-progress debut book… and I’m nearly there (EEEEEK!). And I have been sharing a few of my favorite essays I’ve written over the years with you here so I can focus behind the scenes on the Big Project. :)

Today, I have an essay to share about all of these themes, particularly focusing on one man who showcased this courage and faithfulness for me as his life ended. I only knew him from afar and for a brief time, but I feel grateful to have witnessed how Jim spent his last days earthside. And, strange as it sounds, I believe you also will feel encouraged after witnessing the way Jim lived and died well.

In the meantime, blessings on this All Saints Day, my friends!

Thanks for reading.

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

All Saints

Originally published at Ruminate Magazine’s blog, the Waking (now defunct)

Steve and I had been friends for only a year and a half when he asked me to drive him home from Missouri in our sophomore year of college, so he could sit vigil to watch his father die.

Jim, Steve’s dad, had cancer. What type, I couldn’t have told you. But Steve had confided his father’s illness early in our friendship, death’s shadow already following us around, even as teenagers.

When we arrived after a drive from Chicago to central Missouri, Jim reclined in a hospital bed in the living room, his daughter, son, and wife hovering nearby. Immediately, I felt out of place as Steve’s mother fed Steve and me dinner at the wooden table, mere feet from the dying man. All I could think to do as the family circled the bed after the meal, a hospice nurse in the corner, was to rinse and stack the dishes inside the washer.

In the background of my scrubbing, Jim wheezed. At 19, I had not yet seen death, not up close. I tried not to stare, but I found it hard not to study Jim’s ashen skin, dry lips, skeletal fingers, sunken chest. I did not stay past dinner. I drove back to my dorm room that same night, a six-hour drive in the dark. The next day, Steve called to say that Jim had passed.

Only later did I learn that the day of our drive and vigil was the sacred holiday, All Saint’s Day.1 All Saint's Day is a Christian liturgical celebration that honors the bond between all saints, living and dead. A fitting day to die, in other words, for a Methodist reverend like Jim.

He also wrote, like me and Steve who both fit in as many creative writing courses as we could into our course schedules. Jim had been writing about his death for several years before his death for the local newspaper. Through his column, entitled, “Walking with a Sick Man,” he found a way of expanding his small-town Missouri pastoral ministry to the very end of his life.

Two days before Jim’s death, he published the last installment. By then, he had suffered for four long years from the invisible disease. He describes how he’d recently woken in the middle of the night after a dream in which his oncologist had given him the “all clear.” He’s cancer-free, the scan is empty of errant cells. He imagines the celebrations with his family, his congregation. He counts up what he might do with the time a cure would give him back.

But then, he described a surprise emotion mingled with the imagined joy: regret.

He had caught a whiff of the prize at the end, he wrote, like his son’s Labrador, Scout, nose to the ground. He wrote, “My eye sees something on the horizon; …there’s this scent in the air that is more enticing than anything I have ever smelled; and I am aware that I am hot on the trail.” [sic]

He could almost touch heaven. Only later would I understand the ambivalence his family must have felt reading those words.

Several years ago, a friend of mine died of cancer.

This time, I was thirty, 11 years from Jim’s death. This time, I knew the details of the cancer: stage 4 soft tissue cancer, unusual in a 34-year-old man. He was a rock climber with a young wife, a toddler, and a son on the way.

He, too, loved Jesus and believed until the end that he might receive the “all clear,” the scan that might give him years to witness his son’s first steps, to drop his daughter at the first day of kindergarten, to teach his kids to climb mountains like their dad. But he didn’t make it. He died, too, in February 2018.

In 2017, around the time my friend received the life-threatening diagnosis, I noticed a blind spot in my right eye. A dark ring had appeared at the center and it blocked my vision. With my left lid shut, I could no longer read the minute text on the pages of my Bible, nor the street names on the green signs; I could not see the green of my own iris in a mirror, nor my daughter’s ring of yellow circling her blue eyes, nor the growing number of teeth emerging from my son’s gums like shoots from the thawing spring dirt. No matter where I looked or how, whether I squinted, used eye drops, removed or put my glasses on my face, the cloud remained. It would not be corrected and would not go away.

Before this, I had never even had a cavity. Doctors tended toward boredom as they examined my chart. Sure, I had been declared near-sighted at age 14, just like my parents, but beyond that, I seemed to have inherited the genes of the fittest of the fit: both parents alive and disease-free, both grandmothers thriving into their late eighties and beyond.

So, I found myself wondering, who in the hell loses their vision at 29?

Answer: the same people who die at 34, who leave behind pregnant widows, who fight in wars they do not believe in, who waste away in prisons for beliefs deemed traitorous by totalitarian governments, whose cells fight against their own bodies.

What I did not yet grasp was the meaning of Christ’s call to “take up the cross and follow.” To “come and die.” According to one of Christ’s most noteworthy apostles, that meant, “To live is Christ and to die is gain.” At 29, I had thoroughly imbibed the lie of my immortality.

Then I lost vision, and, one agonizing month later, received a diagnosis: I had a rare retinal disease called Unilateral Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy. Translation: a right-side only (unilateral) sudden-onset (acute) disease of the macula (maculopathy), the central vision of the retina, that had no known cause and seemed to be isolated to one single part of my body rather than a systemic disease that would affect the whole (idiopathic). UAIM was rare, one in a million rare. It had no treatment and no cure.

Here’s what my eye doctor could tell me:

a lesion had grown in the center of my right retina, which had, in turn, scarred and destroyed the light receptors that helped me to see. Fortunately, my left eye was completely healthy and normal. Unfortunately, the rods and cones—the special light-sensing cells in our retinas—that the lesion had displaced and destroyed in my right eye…those were irreplaceable. As in, rods and cones do not heal or regenerate, and their absence cannot be corrected by lenses, surgery, or any other treatment available.

Before that moment, I had not understood my fragility. But then the light switched on, and I could not forget it.

After that, there were more doctor appointments, there were microscopic hemorrhages in my eye, there were trial procedures and medications, there were fights with insurance providers. At one point, I received shots in my eye several times a year, an expensive treatment that my insurer especially disliked.

But in 2023, the shots stopped. The damage has been done, leaving me disabled (low-sighted) in my right eye. Also, thankfully, the lesion has gone quiet, no longer shrinking, growing, bleeding, and scarring one of my most precious sense organs. The disease has receded, apparently.

For now, I have made peace with the vision loss. I am not dead, though I have my share of survival’s guilt whenever I think of my friend’s widow and their two children.

Still, my body is decaying, day by day. Death lingers. I have not escaped its draw and eventually, my body will also succumb.

Perhaps that’s why I feel hope on All Saint’s Day.

Days like these allow space to remember. And now, when I pause on this day, I remember Jim. Jim knew that this life would not endure, that these bodies fail us, and still, he hoped. He hoped for himself and for those he left behind.

By his example, I, too, believe in eternal life, a life without end, life in the presence of God, a presence that restores sight and joy to those bereft of both.

And Jim, if you’re listening, pray for me. Pray that I’d continue to believe, even to my last breath.

Notes

BTW, we’ve heard from my good friend Steve Slagg before! You can read about how coming out got him excommunicated from the Anglican Church of North America (ACNA).

AND Steve’s also a musician. He wrote a whole album about All Saint’s Day and his father’s death which is haunting and shivery and tearful and liturgical and SO WORTH YOUR TIME. I recommend especially if you need a good cry.

My parents are 91 and 92 years old, and my mom often says that she’s ready. She is almost blind from macular degeneration, her legs are very weak, and she doesn’t understand why she’s still here. Sometimes I wonder if she has ‘caught a whiff of the prize at the end.’ Personally, I think neither one of my parents wants to leave the other one. Anyway, thank you for a wonderful article reminding me to remember that great cloud of witnesses!

Beautiful. Thank you for sharing.