the Empathy List #161: The American Evangelical Church Has a "Woman Problem"

As in, we're heading for the exits.

Hi friends, Liz here.

Much ink has been spilled in the past five years about women and the American Evangelical church. I know cause I’ve expended much ink myself, and because I have left behind the borders of White American Evangelicalism within which I grew up.

I really did used to be a good evangelical. What am I now? I suppose that now, I’m just a progressive evangelical—because you can take the girl out of church, but I’m not sure you can take the evangelical out of the girl. ;-)

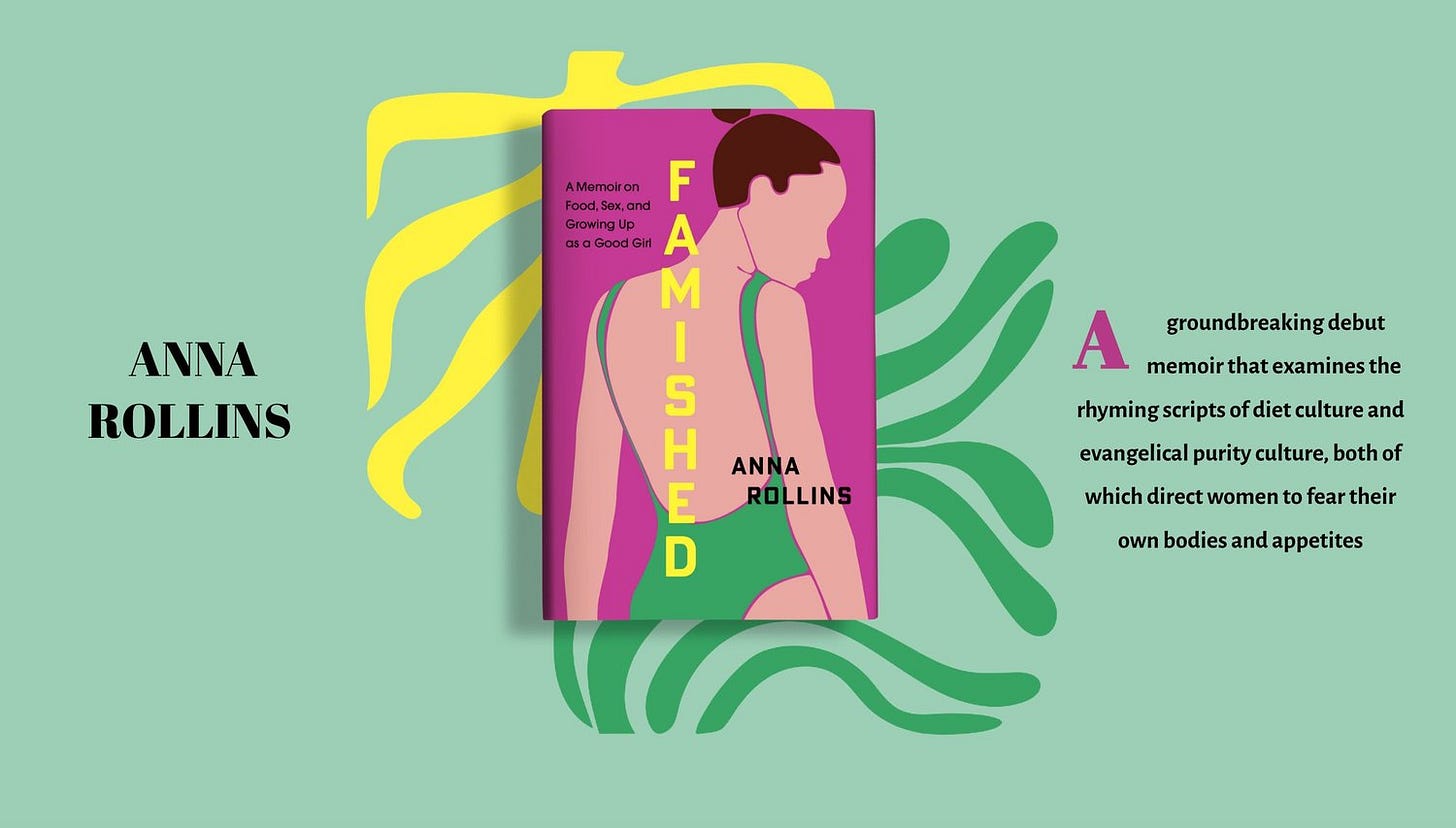

This struggle with church and gender finds an insightful narrator in Anna Rollins. She’s published every media outlet you’ve heard of, and now, her journalistic memoir, Famished: On Food, Sex, and Growing Up as a Good Girl, narrates how diet culture intersects with purity culture.

I MEAN, COME ON, THIS IS THE BOOK WE ALWAYS NEEDED.

I love a good memoir, and I especially love one that spills the tea on the evangelical culture that I have both adored and despised in equal measure. And the ties between diet culture and female purity—rhyming scripts, Anna calls them—have hardly been discussed. There’s a lot to say.

Anna embarked on a monster reporting journey, talking to dozens of us who lived through both the “heroin skinny” of the 2000s and the “True Love Waits” craze. And this book is her own story and theirs. You already know these stories because if you’re here, reading this, I have a hunch that her story and yours and the stories of the women you love does not look so different.

And we especially need this book right now—when “heroin chic” is back and Christian Nationalist pastors are telling single women on the the internet that if they want to get married, then they need to lose 20-30 pounds. (How does it feel to live with your foot in your mouth permanently, Joel Webbon?)

Anyway, I hope you’ll pick up a copy for yourself this Christmas. (TREAT YO SELF!)

Thanks for reading, pals.

I take it slower around December. You’ll hear from me at the Empathy List at least one more time this year, perhaps twice. But I don’t post according to my normal weekly rhythm.

I hope your Christmas and advent season is exactly as you need it to be. For me, that means restful, joyful, and connected to my people… and trying my best to mostly ignore the men in the White House. (Not sure if it’s possible. We’ll see.)

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

The Woman Problem

by Anna Rollins

I am a Christian woman who has struggled to remain in the church.

I detail this struggle at length in my forthcoming memoir, Famished: On Food, Sex, and Growing Up as a Good Girl. Like many women, I’ve grappled with blatantly patriarchal interpretations of scripture. Loyalty to male power has led church leaders to excuse the inexcusable: covering up sexual abuse scandals in the Southern Baptist Convention, excusing sexual misconduct by celebrity church leaders like Ravi Zacharias and Bill Hybels, and showing allegiance to our self-confessed predator President, just to name a few.

This same forgive-and-forget nonchalance has also informed interpretive readings of Scripture that defend indefensible male behavior in the Bible. I’ve listened to many sermons that engage in intellectual gymnastics to justify male-coded sin, blaming Bathsheba for her own assault because she had the audacity to bathe, for instance.

So, when I read Liz Charlotte Grant’s gorgeous book Knock At the Sky, I wasn’t surprised to see that early church fathers engaged in spectacles of creative reinterpretation to excuse Abraham from the sin of bigamy after he impregnated Hagar, his wife’s slave.1

Not only did Augustine blame Abraham’s wife Sarah exclusively, claiming a “defect in her nature” (127) he also purported that somehow, Abraham refrained from having any lust during his encounter with Hagar. Ambrose, a bishop of Milan, argued that impregnating Hagar was a matter of “moral obligation” after the population had been wiped out due to the flood (this feels like a pronatalist argument I may soon hear on the news). And Didymus the blind insisted that the sexual act between Abraham and Hagar was performed “without passion,” as if the presence of pleasure is more of a sin than another human being’s transactional exploitation.

There is much historical precedent for the “plain reading” of scripture to side with male power and female oppression. If male sin isn’t reinterpreted into nonexistence, it is often quickly forgiven with little regard for justice. Men can fall and rise and again, but a fallen woman has little hope for ascent.

It shouldn’t be a shock, then, that women are leaving the church in unprecedented numbers. This is unsettling for the church, not just because losing a demographic is concerning, but because (historically) women volunteer in church more than men. Mothers are integral to passing faith traditions on to their children.

During the Boomer generation, men were more likely to disaffiliate from the church than women. But those demographics have now flipped. As more younger women identify as feminist, they have rising concerns about gender hierarchy in the church.

Women in these surveys say that their decision to leave the church wasn’t based upon any one thing. Rather, they experienced a steady accumulation of negative experiences based upon gender.

I can relate. I grew up attending a Southern Baptist church (while enrolled in a fundamentalist Christian school). In college, I longed for less rigidity and more grace. I found that (to some extent – smoking and drinking were no longer contraband, at least) when I joined a Reformed Presbyterian congregation.

Still, I couldn’t escape the sexism. My desire to leave the church was a slow burn, a gradual realization of all the ways my identity and value as a woman had been minimized – and weaponized – in the church. The harsh comments about female bodies by male religious authority figures. A friend’s assault by a youth pastor, and the lack of accountability to which he was held. The false promises of purity culture. The expectations for women to endlessly serve without ever receiving discipleship or support. The consistent use of exclusively male pronouns for God and humankind, alike, from the pulpit.

I felt like I had two options: be perfect and conform to rigid gender standards which did not seem to make room for my needs, interests, gifts, or humanity. Or leave and reject Christianity entirely.

In my reported memoir Famished, I detail my own faith crisis. I describe an inflection point brought on by personal trauma. I didn’t want to leave the church, but I wasn’t sure how I could continue to stay.

As I wrote the book, I interviewed dozens of women who grew up with a similar religious background and asked the question, “How did your experience in purity culture impact your relationship with your own body?” Their responses were loaded and long. And their modes of healing varied, too. Some had left the church entirely, while others were able to still find faith in the Christianity.

But no woman I spoke to felt neutral. No woman remained unscathed by the wounds of patriarchy disguised as the righteousness of God.

One of the chapters I was most drawn to in Knock at the Sky was about Hagar, the enslaved woman who was impregnated by Abraham and then banished into the wilderness after Sarah could not manage her own jealousy. In Grant’s rendering, I saw Hagar anew: an enslaved woman with no power, now pregnant (nauseated and vomiting, perhaps), famished, and without hope in the desert.

But God found her there. Banished and alone, God sought her, even though she’d been rejected by Abraham, the patriarch. God asked Hagar to return to her home. Who would have blamed Hagar for refusing? And yet, where else was there for her to go? She had no other place to turn. Out in the desert, she would die. And so, Hagar returns to the home of the patriarch, the site of much exploitation.

But this is not simply a narrative about Hagar quietly submitting to unjust authority. This story is much more hopeful than that, because in the desert, God makes Hagar a promise: her descendants would be “too numerous to count.” She wasn’t being called to shrink, but to expand.

Hagar, a fallen woman, would rise again. God would see to it.

This kind of promise is what gives me courage to continue in the church, too. I have experienced the precarity and scorn of patriarchy in my body as a woman. I have been in the desert, and I have experienced the pain and scars of embodied injustice. And yet, I felt the call to return home. Not because I am blind or ambivalent to injustice. The injustice is real, but I have hope for a better future.

About the Author

Anna Rollins is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, Slate, Salon, Electric Literature, Joyland Magazine, and other outlets. She is a 2025 literary arts fellow with the West Virginia Creative Network. Follow her @annajrollins on Substack and Instagram.

And guess what? Anna’s memoir RELEASED TODAY: Famished: On Food, Sex, and Growing Up as a Good Girl. Let’s support her!

Liz here: I did not ask Anna to mention my book. She’s just a fab supporter of her writer friends. Seriously, Anna, you’re the best.

Liz, THANK YOU! Thank you for sharing your space — and for such a beautiful endorsement. And also, Joel Webbon?!? 🤯🤯🤯 I wish this topic would stop being so timely.

There's another author who has written on this topic in her recently published book: For the Love of Women by Dorothy L Greco. She writes about misogyny in terms of healthcare, government, workplace, media & entertainment, church, and intimate relationships. There are several articles, reviews, and podcasts about the book online. It sounds to me like Anna's book would be a good companion read to Greco's book.