the Empathy List #152: Are We in Political Hell?

Reimagining the theology of heaven (and hell) helps.

Hi friends, Liz here.

It’s been a while since you saw my name in your inbox. (I’m hoping that this break doesn’t mean the majority of new subscribers won’t open this email… tbd)

I do not write this email in the summer months. Which I know is CRAZY to the hustlers among you. How could I neglect my AUDIENCE? Don’t my readers NEED TO SEE MY NAME to remember me? Isn’t that the CARDINAL MARKETING RULE, always be forcing your product in front of their faces?

#1 Always be present, never stop never stopping.

However, in my case, I myself am the product. I am a one-woman show, with ZERO help from ai. This email is conceived by me, written by me, edited by me, copyedited (usually poorly) by me, and then sent and marketed by me, too. …And me simply cannot make me-self send you emails in the summer months.

I have learned to attend to that inner voice of my body when she speaks, “I’m weary, and I must rest.” And I aim to care for this inner being as tenderly as I care for my children.

Sometimes, there is no stopping possible, and I must press in, embrace the impossible season, and persevere (as I did during my book’s launch in early January).

More often, however, I need to pause. Rest is the spiritual practice I hope to model for you, too: you are not a capitalistic machine, but a body, and bodies require rest to stay well.

I have learned, too, that creativity is not a faucet to turn on and off, but rather a mycelial network. Growth happens below the surface of the ground before any mushroom appears above the soil.

In other words, creativity requires periods of privacy. In privacy, I write shitty first drafts that become compost for the drafts to come. And nobody reads my shitty first drafts except the worms. 😉

I hope you’ve had a similar sort of composting summer and that you, like me, have now entered into a season of harvest after a long rest. I’m back to writing in public again with plenty to say, because ready or not, it’s tomato season, y’all! And that’s my cue to return to normal, daily life rhythms, ready or not.

So you’ll be seeing this email weekly-ish, with occasional breaks (which I’ll announce). Sometimes it’ll look like “Curious Reads” in your inbox. Other times, it’ll be numbered “Empathy List” editions. Regardless, you’ll be seeing me more often.

Truthfully, I may not be totally ready to return to the ordinary creating. I have felt especially disheartened and exhausted by this public season.

I want to scream thinking about what is happening to the democracy of our nation, our policies, our nonprofits, our international partners, our refugees. I am teary often.

Really, it’s not policy that disturbs me, but people.

When I think of the people targeted—the children who are afraid to go to school because ICE—or a man with a gun—might be waiting for them, migrants rounded into white vans and deported to prisons in unknown countries, LGBTQ couples afraid their marriages could be annulled by biased legislators, and on the other hand, the hardened politicians stroking the ego of the despot whose sins include the sexual exploitation of underage women—then I can hardly breathe.

Timothy Snyder, in his book On Tyranny [THIS IS ESSENTIAL READING BTW—I recommend the brief graphic novel version], writes that we, as Americans, have forgotten that democracy is fragile. We have forgotten the tremendous effort required to hold back the tide of authoritarianism, fascism, and dictatorship. We have forgotten the rushing, consuming power of greed, embodied by the top 1% of our society.

And we have forgotten, in a sense, our identity as Americans.

The revolutionaries built America on protest against authoritarianism. That remains the origin point of our story (whether the founding fathers really meant it is a question for historians to parse).

We have believed the lie that the state of our democracy can never change, not really, and that the status quo is good enough.

And that forgetfulness has made it far too easy to blaze past the status quo into a hell of our politicians’ making.

Do I sound like a Debbie Downer? Maybe I am.

It’s not that I have no hope. I believe we can change things. In fact, my next book will be a compilation of protest stories, including writing about the protestors within the pages of the Bible. (more on that to come…)

BUT I never want to mislead a reader about the state of affairs, as I see it. I will tell you the truth.

And from my very limited sightline, the American state of affairs looks grim, and I confess that I feel afraid. As a writer who has never found a comfortable place within the institutions of either church or state, I do wonder about where the current censorship will take us, intellectually and politically. (Remember McCarthyism?)

Let me put it this way: I have renewed my passport, made my husband renew his passport, and I have applied for passports for my children. Just in case.

In other words, I’ve had a manic and joyous summer—planting and watering vegetables, writing and outdoor swimming pools, barbecue and fireworks—and that, right there, is my version of heaven.

But this reality of fear and dread, oligarchy and control? That is my version of hell.

What is Heaven Like?

Theologically speaking, I trust that God is in control—yesterday, today, forever. Yet the vision of heaven makes me hope in a way platitudes (however true) just don’t.

When I think of heaven, I think of exploration. I have this theory that, if heaven really is a place without loneliness and without cost and without the possibility of pain or hurt or death, then, finally, we humans will discover the entire breadth of the universe, and we’ll do it together. We will measure out every mystery, name every species, reach every deep corner of the ocean and every far edge of every galaxy that God has made. Of course, we will be able to breathe underwater and survive the outer reaches of space. We will not need air, we will not fear falling or drowning or expiring with no way to return to the home planet.

Here’s my reasoning: we know that God has made all that is, and that God made the entire cosmos as a generous host, welcoming us to the table. But we, fragile creatures cannot see and experience the wide range of God’s gifts because of our limitations. So, when the limitations disappear, then, I hope, we will finally be able to plumb the depths of God’s goodness and creativity.

I believe that’s what heaven is for. Our curiosity will have no limit, our bodies no end, and the bounds of the universe will expand as we expand with it. Basically, heaven is a scientist-explorer’s dream.

And you better believe I’ll spend a century or two floating in the void of space with my dearest friends (if they’ll come), just to see what exists on the other side.

Now, whenever I experience that pang of regret of not enough time, I remember the people, the places, the learnings that will meet me on the other side of the veil, and I am comforted. Heaven is the people I love who have moved away, the book ideas I’ll never have time to write, the careers I wish I could have tried, the places I wish I had the funds to visit. In heaven, I will have all that and more.

The other side: yup, I still believe in hell.

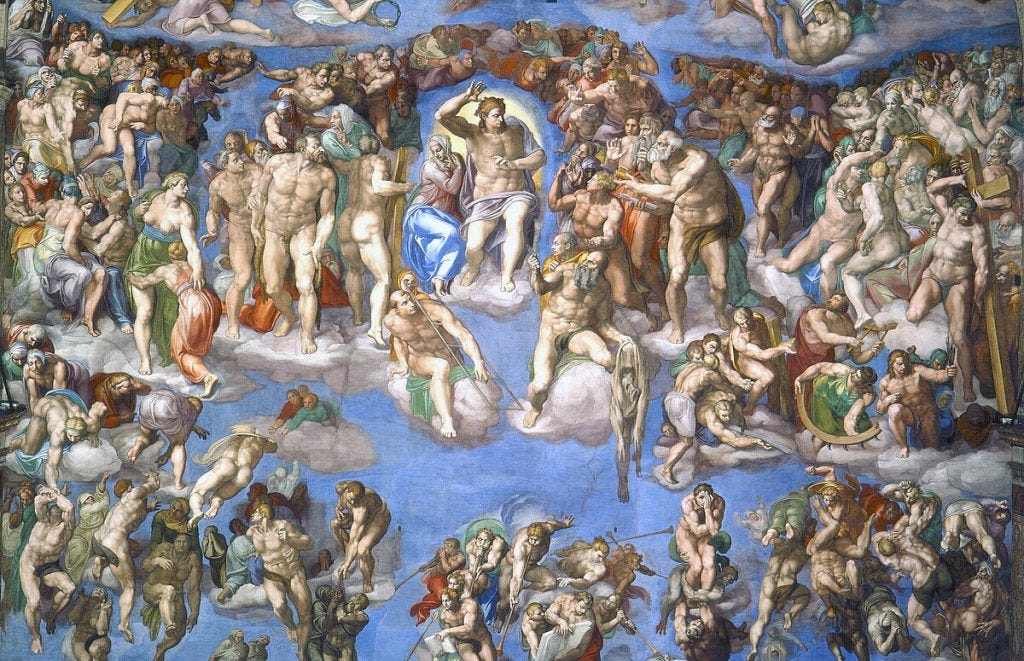

Many theological progressives I know do not believe in hell. They cannot abide the punitive, vengeful Father God, as pictured in Michelangelo’s “The Last Judgment.”

BTW I wrote an essay about viewing this particular medieval mural as a bratty teenager. You’ll probably enjoy it. ;-)

I understand why my friends want to ditch hell, but I disagree. I disagree not because I want my enemies to exist in eternal torment after death, but because I cannot make sense of the black liberation and womanist theologians without hell.

What kind of liberation exists without the oppressor facing the weight of justice?

I cannot begin to tell you the depth of these theologies myself—I don’t have time today to make the attempt, so perhaps that’ll be an essay for another time.

However, I have realized that de-colonizing my faith and theology means that I trust my own white privileged ideal of theology less than I trust the theology of those that my people have placed below us at the bottom of the ladder, the ones whose hands we have crushed as we have climbed.

Those theologians believe in hell, of a kind. And so, trusting them, I believe the same.

Even so, when I think about hell, I still do not mean “eternal conscious torment” like the powerful white male theologians prefer.

To me, heaven and hell look more like C.S. Lewis’s fictional surrealist depiction of the afterlife in The Great Divorce.

The allegorical tale sets an anonymous narrator in a “grey town,” where it is perpetually raining, indoors and out, and he eventually finds a bus stop with a line of travelers. Some end up boarding the bus and riding to a colorful, enormous land above, while most retreat further into the grey town. Once the bus arrives at its destination, the narrator meets a guide, who explains to him the state of affairs. The above—thicker, larger, more colorful, and more solid than matter on Earth— represents the truest reality, that is, heaven. It turns out, joy is too great to imbibe all at once, and so those who arrive at the pearly gates must gradually adapt, inch by inch, one blade of grass at a time.

By contrast, the grey town lies below in a mere crack in the ground of heaven, microscopic and more ethereal than anything above, and those who stay retreat further and further into its depths, moving further from companionship because they cannot stand to share the same space as another person.

“The gates of hell yeah are locked on the inside,” Lewis says.

And his narrator’s guide, George McDonald, says, “There is always something they [those who keep themselves in hell] insist on keeping, even at the price of misery. There is always something they prefer to joy - that is, to reality.”

The damned refuse to leave the mundane, joyless, discomfort and despair of their lives, not so different than their lives on Earth, rejecting the offer of God of companionship and release that occurs through the act of repentance. The theory is that with God, there is joy, goodness, companionship, and every one of the best things about living, while the absence of God is the worst of life. Those in hell pick themselves over God every time.

Lewis writes, “There are only two kinds of people in the end: those who say to God, ‘Thy will be done,’ and those to whom God says, in the end, ‘Thy will be done.’” God releases those in Hell to their self-imposed isolation from others and from God, refusing to kick down the door to impose God’s presence on those who don’t want it. God allows them to say no.

One of the most moving parts of Lewis’s take, however, is that he describes the rewriting of the past in terms of the present of the afterlife:

“The good man’s past begins to change so that his forgiven sins and remembered sorrows take on the quality of Heaven. The bad man’s past already conforms to his badness and is filled only with dreariness. And that is why, at the end of all things, the Blessed will say ‘We have never lived anywhere except in Heaven,’ and the Lost, ‘We were always in Hell.’ And both will speak truly.”

Lewis’s theory is that the revolution of a life begins today and stretches into eternity so that the quality of a life can take on either the character of heaven or hell today.

Lewis says, those who seek heaven will find it; those who refuse it will self-isolate to their destruction.

In this picture, God is so devoted to the freewill of God’s creatures that God will not force love down their throats. And as I’ve said elsewhere, I can accept this because I have come to understand why: untethered love is the only love worth having.

I suppose these visions of the afterlife are exactly the reason I have not succumbed to despair.

Despite the injustice, greed, violence, dehumanization, fear, and dread of this moment in America’s history, I feel a deeper certainty that this life is not our one shot. I cannot explain how I know that a truer reality exists, but I have never doubted it. My bones know what is right and what is wrong, and I am convinced that spending my life for the right is the only path to walk.1 The deepest justice cannot, will not be conquered—not by bribes or police battalions or detainment or death.

Whether we witness this justice in our lifetimes or not, I believe with all my heart that justice will, one day, arrive. For those at the bottom, that is very good news. For those at the top, I urge repentance—yesterday.

In the meantime, I will continue summon the courage to work, write, and pray for the reality of heaven here on Earth. That’s how Jesus taught us to pray, after all, and it’s also the only next step we have. Do not lose heart.

Thanks for reading, my friends.

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

Tell me: how are you nurturing your courage?

BTW, I’m very aware that this it is easier to say I will spend my life for justice as a white middle class lady in the suburbs of Denver than it is to truly spend my life for justice. That said, I’ve started to plan for the possibility that I could be arrested during a protest, or that, at some point, writing bluntly about political failures could become illegal. I realize that I sit in a privileged place, and I very much want to use every ounce of that privilege for the common good. By which I mean to say, “Hi, nice to meet you, my name is Liz, I’m a Christian socialist, and I’m working on my rap sheet.” lol

I love your description of heaven. That is what I hope for, although I've never been able to fully articulate it. I've always loved the concept of "further up and further in" from C. S. Lewis's "The Last Battle." I think we will forever be growing, learning, exploring and creating, each of us becoming ever more ourselves, distinct from but in harmony with each other, God, and all creation.

I first read "The Great Divorce" way back in high school. At the time, I loved the idea, but felt it was a shame his concept wasn't true," thanks to the "eternal conscious torment" indoctrination I'd received. Now, I think he's (almost completely) right. My one objection:

While I don't believe God will force anything, even heaven, on anyone, I do think a lot can happen over ... eternity. Given infinite time, I think surely everyone, yes everyone, would eventually choose God. With my current mindset, I admit I wouldn't necessarily welcome that, but I imagine those feelings would be different then. And eternity is a very long time. If we truly know and are known then, I suspect the question would feel pretty moot then.

I'm interested to hear what you think of that. In many ways, I'm not too concerned about the question of what happens after death, since the only answer we can truly have now is that at don't know. But I am very concerned with understanding who God is. A God who will eagerly wait a literal eternity for his creation to turn back to him is very different from a God who will doom people to eternal joy or eternal torment based solely on their condition when his secret alarm clock rings.

What a treat to find your post in my inbox this morning, after your idyllic summer break! I too love the heavenly joys of summer, the splashy family pool parties and the fireflies and scents of ripening figs and basil and tomatoes from the garden. Your vision of heaven is just what I needed to read today. My 92 year old mother is likely in her last weeks or days of life, and I've spent countless hours by her side. Your words are a comfort and hope to me of the wonder and joy that is to come for her. She's barely able to swallow, but when I put a little bite of her favorite chocolate truffle in her mouth, she has a moment of bliss. Even though my Dad has dementia and doesn't recognize her as his wife, he still kisses her twice upon every greeting and holds her hand and sings their love song and favorite hymns to her. Surely the God that created these gifts for her to enjoy must have something marvelous in store for her in eternity!

I too am sorrowful for the current state of our nation, especially for the America that my grandchildren are being raised in. My frequent explanation to them is that the forces of evil are real and at work, and we must spread all the good we can because we follow God, and God is good and just and love.

Thank you for your timely post for my heart today.