the Empathy List #135: A Debut Author's Publishing Story, Part 3

Another Day, Another Manuscript Dead-On-Arrival

Hello friend, Liz here.

Remember: every artist success story is preceded by failure and rejection. ;-) (Does knowing that help to tame the envy monster? It helped me!)

In part 1 of this special publishing series, I described the origins of my desire to become a writer, a manuscript of short stories I wrote and that the indie presses of the day roundly rejected (40 indie presses rejected my first book! Four-Zero!), and the encouragement that kept me from quitting.

In part 2, I described the paradox of a burgeoning career and the shattering reality of needing to work my butt off in lieu of “getting discovered” (rude).

Today, in part 3, I’m telling you the sad story of my dead-on-arrival memoir. It’s a doozy.

Another Failed Manuscript

So, remember, I’d started one memoir already, but had redirected due to my surprise disability in 2017. One paragraph piled onto another during my morning writing sessions, and I suddenly realized that I was writing a disability memoir. I submitted that book to a residency program where I could receive feedback from Lauren Winner, another memoir idol of mine, and while at the residency, a friend connected me with a literary agent who eventually signed me.

From there, I assumed the trajectory toward the stratosphere was inevitable. Because that’s how it happens, right? A big single moment changes everything?

Except it didn’t. Have you ever heard me talk about this memoir as an actual book? Nope. The book I’m releasing in January (UM, A WEEK?!) is my first published book. So, what happened to the disability memoir?

The answer is complicated because revealing publishing secrets is taboo and frankly, I don’t want to be blacklisted (which happens). So, I’ll give you the story in broad strokes:

The agent with whom I signed was world-class, still is. I feel deeply grateful to him for plucking my manuscript out of the slush pile. (I believe mentioning a mutual friend in my query helped to get his attention). But he could not sell my memoir. No matter how many times we tried (three rounds of querying over two years), no matter how many revisions I made in overhauling the entire manuscript (four), we could not get an editor to buy it. In fact, we couldn’t even get an editor to meet with us.

Editors did read the manuscript, however, and from that reading, we heard that they “liked my writing, but...” From the general market editors, we heard that my perspective was too Christian, too internal (“nothing happens, she just stares at her phone and cries”), too niche, too varied in content, which would make it hard to categorize and sell (“is it self-help or medical mystery memoir or childhood abuse memoir1?”). In the Christian market, we heard that editors had no idea how to sell a memoir, in fact, memoir as a genre had become toxic within the religious publishing industry. And, of course, we heard that that my platform was too small.

Platform, for those who do not know, is a word that refers to an author’s ability to convert sales. When these editors told me that my platform was “too small,” they didn’t mean numbers of online followers alone, they also meant who I knew. I had no organizational connections, hardly any author friends to ask to promote the book, and no plan to make up the difference. So how could they sell a memoir from a non-celebrity who had no plan to sell herself?

I was devastated. I believed, and so did my agent, that my memoir would sell because it was good. I believed that good writing equalled success. That good stories needed to be told, regardless of their marketability. I still believe this, and I will continue to stubbornly argue that the publishing industry writ-large must publish more memoir from non-celebrities because these stories are often the most important stories for others to hear, read, and see. These are the stories that teach empathy, change internal narratives, and offer visions of new lives to readers.

That said, in 2020 and 2021 when I was pitching my memoir and receiving universal rejection, I had forgotten that editors have bosses and investors to answer to. The publishing industry is exceedingly volatile, affected by the wider market (like recessions), by new technologies, and by the hard-to-predict trends of the zeitgeist. As in the movie industry, no one can reliably predict a “hit” or a “bestseller” because so many factors contribute to a book’s success or failure2. And so over time, the “nos” I received have started to make more sense.

But I was still not out of options when the bigger presses turned me down. My agent typically worked in the spheres of “the Big 5,” and so did not pitch my book to publishing houses of other tiers (as far as I knew). However, before I’d been signed and become an agented author, I had sent around some queries myself and two offers materialized: I could publish with a little known independent press (zero advance or marketing budget, but no fees to publish) or I could publish with a large, well-known hybrid publisher known for being selective and publishing only the best self-funded memoirs on the market (large upfront fees, but extremely well-connected).

Sadly, I could not afford the fees with the hybrid press and did not imagine a successful kickstarter, despite my best efforts. And the offer of publication from the tiny indie press also dissolved when I informed them during the contracting process that my family objected to the publication of the memoir. (The editor me, “We need signed permission forms from all those you write about in your book. We cannot afford a defamation case.”)

So, that was that. One memoir, dead-on-arrival.

Returning to the Page

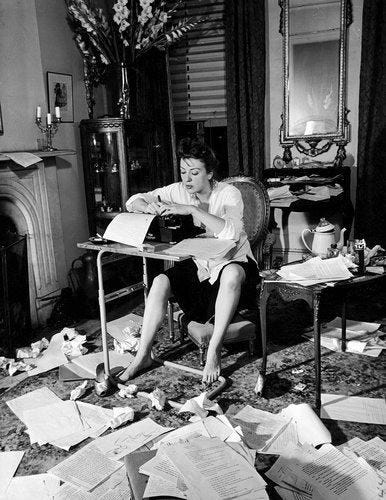

But you already know, that was not the end of my story. To become an artist, you must develop resiliency. When you first begin the long climb toward mastery of a craft, every work you make is a shitty first draft (even when it’s not your first draft).3

As American novelist David Eddings puts it,

“My advice to the young writer is likely to be unpalatable in an age of instant successes and meteoric falls. I tell the neophyte: Write a million words–the absolute best you can write, then throw it all away and bravely turn your back on what you have written. At that point, you’re ready to begin.”

Throw out your first million words. It’s not that they’re trash, per se, but they are not the right words, they are not your words. You are writing your way toward your work, and it will take one million tries to get there.

By the way, if you need encouragement, check out this Reddit thread on famous writers’ first drafts vs. the finished book (TLDR; EVERY author writes shitty first drafts):

Frankly, I think this advice about chucking your first million words applies to publishing, too. If my experience is any guide, I believe it proves that to publish a book, you must create a lot of material which editors can choose from. By making and making and making, undeterred by criticism or doubters or rejection, but stout-heartedly returning to your desk regardless, you increase the odds that one of your manuscripts will resonate with the right decision maker at the right time.

If you’re struggling with this advice, I understand. I felt furious that my work—which was good and resonant and necessary, which would have helped so many people—was overlooked in favor of shallow and safe alternatives (in my humble opinion). So many book deals happened around me as I stewed in my own fury. Eventually, I realized that my fury accomplished nothing good in me. Bitterness is its own consequence.

And the fact is, publishing is a conservative industry that hates to take big bets. The first book is the hardest book to sell. The bet that publishers place on you is untested, and there is little they can do to predict how that’ll go. Will the book sell? Will they get their investment back? Will you be a joy (or a nightmare) to work with? WiIl you even finish the draft you’ve promised them? It helps when an agent can vouch for you, but then again, a literary agent has a vested interest in your success since they work on commission (they get you a book deal, and they get a cut, very much like a realtor). And sometimes, most times, publishing bets do not pan out and lose the publisher money.

So, while I worked through my grief and anger that my dreams of becoming the next Cheryl Strayed had evaporated, I started to write something totally different.

By this time in 2021, my doula business was long dead, the worst of the pandemic had begun to recede (which meant my kids were back in school full-time, and no longer under my feet all day…), and I finally had time to think, breathe, and write again. I began to explore an idea of making my own version of an illuminated manuscript of the Bible with a couple books of the Bible in mind. I was lucky enough to nab another residency and while there, I chased this idea down further. That manuscript would become Knock at the Sky, my first published book. (more on that in the next installment ;-))

It Was Never About the Writing

Before I wrap this installment, however, I have to tell you that what actually led to my book contract was not my writing, but my devotion to making writing friends.

In 2019, when I’d joined Redbud Writers’ Guild and attended my first writing residency, I’d just begun to see the benefit of knowing other authors. But in 2020 (or was it 2021?), I made a resolution to make the entire year about getting to know more people in my industry. That year and every year since, I’ve made my writing friendships a top priority. I try to read and share the work of my friends, to schedule regular times to talk on the phone or over Zoom, to support newer writers who want to “pick my brain,” to endorse others’ books when I can, to speak to authors when opportunities arise, and to share what I have with others. I do not consider this mere networking, but a chance to cultivate authentic relationships with colleagues.

MFA circles call this “literary citizenship.” Then again, I have found that such “citizenship” often comes with competitive undertones and more than a dash of hierarchy amongst writers of different caliber, genres, or “status.” And I hate hierarchies so much. I am egalitarian on every level, and I refuse to compete with my colleagues.

Instead, I aim to collaborate, to seek equity, to use capitalism against itself—after all, we know that when workers join together in a fight for fair wages, treatment, and status, the powerful are forced to concede. When authors combine our efforts and our audiences, we all succeed. Collaboration is the healthiest and most powerful form of collective action, and though authors have often been explicitly taught that other authors are our competition, the fact is that acting as individuals hurts us more.

I could say SO MUCH MORE about what I hope for the publishing industry in the coming years, but as that’s irrelevant to the story at hand, I yield my time. ;-) [Steps off soapbox.]

What I meant to tell you was that there’s no way I would have been offered a book contract without my author friends.

My author friends wrote pre-endorsements of my work that I included in my proposal. They emailed their editors on my behalf to vouch for me. They introduced me to my current agent, John Blase, and to my former one, too. They read my words and gave me early, needed words of encouragement. They endured all my good writing news in the past year in group chats ;-), and they also talked me through the bad days.

In the publishing industry, “who you know” matters more than writing well. Yes, your friends will have business connections, sure, and when you can sit in front of an publishing executive, your chances of getting a book deal dramatically improve (an anonymous email cannot compare to a face-to-face interaction). But that’s not what I mean, really. For me, becoming friends with your colleagues allowed me to persevere through the worst and best the industry threw at me. These dear author friends knew what it was like to walk this particular, strange, pot-holed road known as publishing, and they were patient with me as I walked it. Lean on the experience of others, ask for what you need from dear friends (and be willing to accept their “no” as a complete sentence), and offer yourself just as freely.

That kind of genuine care is immeasurably more valuable than any book deal. And your life, your-self will be richer for having invested in people above objectives.

To these friends, I say a tearful THANK YOU!!!

To be continued…

Next week will be the last of this special publishing series. I’ll finally be discussing my about-to-be-released book, Knock at the Sky!! ON ITS RELEASE DAY!! 😁 So that’ll be fun.

Thanks for reading, my friends.

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

Can I ask you for a favor? Go pre-order my book!

The book releases in one week. So, help a girl out and preorder now, while you’re thinking about it.

If you’ve already preordered the book for yourself, thanks for supporting this newbie indie artist!! Now, please go tell a friend to go preorder, and voila, you’ve created a mini book club. Or if it’s in budget, buy a copy for that friend because it’s the gift-giving time of year. 😜

Oh yeah, I forgot to mention: somehow, the memoir I’d begun about my eyeball turned into a memoir about the heartbreak of walking through a life-altering diagnosis without family support. Because Lauren Winner, bless her heart, had told me at the memoir writing workshop that while my completed memoir I’d submitted was good, I still had not found the story. As soon as she said it, I knew she was right, and I knew that the story was that I’d gone no-contact with my family-of-origin six months prior to my eye calamity. Sigh. I did not want to make the memoir about them, however, and so I disguised them as best I could. I used no names (neither my maiden name or their first names), did not add any identifying details whatsoever (mentioning jobs, physical attributes, locations), and in fact, I did not even name the state in which I had grown up. I even signed up myself (and my whole family, unbeknownst to them) for deleteme, a privacy service that which would excise any mention of them from the internet, so as to keep their identities truly anonymous. Not that that mattered, in the end…

Even “success” and “failure” are subjective words in the industry. When I was pitching my memoir, an instagram following of 10K was considered successful; now that number has increased to 20K or more. And sales numbers that would equal success in one publishing house for one book would mean failure for another. I found Courtney Maum’s assessment of the relative nature of success/failure helpful in her book Before and After the Book Deal (from pages 211-212):

How many books does my publisher want me to sell?

…Most publishers don’t expect you to earn back your advance,…but all houses hope you’ll sell through your initial print run. …here’s what select editors considered successful sales numbers for a debut novel:

Independent publisher sales for a debut with decent buzz: A veteran indie publisher who preferred to remain anonymous said they considered five thousand copies a successful sales number for a debut. “Anything under two thousand I would consider a disappointment. Anything over eight thousand I would consider a hit.” Another independent publisher… echoes these sentiments: “For a debut, we’d like to get near five thousand copies total sold, print and ebooks combined.”

Mid-house publisher sales for a literary debut with decent buzz: A third industry veteran agreed that there are so many factors at play that it’s hard to cite a number, but for this particular editor, ten thousand copies “would feel really good.”

Big Five sales for a literary debut with a lot of buzz: A Big Five editor who similarly preferred anonymity said that although it really depends on the advance [bigger advance, bigger sales expectations], recently the market has been tough, so she personally breathes easier when hardcover sales reach fifteen thousand.

Note that these success metrics are the highly subjective opinions of individual editors at various publishers, and that they are generally referring to the lifetime sales of a book. Even so, the most sales for most books will happen within the first 1-3 months of a book’s life, which means that most authors should near these numbers by that time. It is possible that a book has a resurgence of sales, but it’s not probable.

Ira Glass, the founder of This American Life, describes this process of mastering a craft so well in this illustrated version of an interview he gave about making radio, and I echo his conclusion: KEEP MAKING.

First off, your gifs are on fire today, haha! Also, I loved reading every word of this. Nodded my head off by the time I got to the end when you were talking about writer-friendships. I would be nowhere without my writer-friends!

My first time reading you! Thanks for being so honest, and congrats on persevering!!!

As a no -published writer who writes a lot on substack about hope and disability and medical and stubborn persevering (mainly around my baby’s diagnosis and medical journey and how it’s changing me as well), I would love to one day “pick your brain!” Even if your memoir didn’t sell- such beautiful words I am sure you pinned!

Despite everything- you’ve kept going!!

While I love writer friends (would love to continue to read you!) it is sooooo sad that publishing is also who you know! But in the end, writers are the best at knowing how to climb the mountain necessary and say, “well, I got a lot of friends in the process!” Ha!