the Empathy List #115: I'm Not Headed Home for the Holidays

Taking comfort in Jesus's model of family conflict and boundary-setting.

Hello friend, Liz here.

This year I will not be heading home to the East Coast to spend the holidays with my extended family. Like the six previous years before, I will not spend Christmas or any of the holiest of Christian holidays sharing sweet potato casserole and sliced ham with my parents.

The reason for the distance between myself and my family has not arisen from politics or illness. Actually, I stopped speaking to my parents years ago due to dysfunction and abuse within my family of origin, despite all of us being Christian.

And that makes this time of year…complicated.

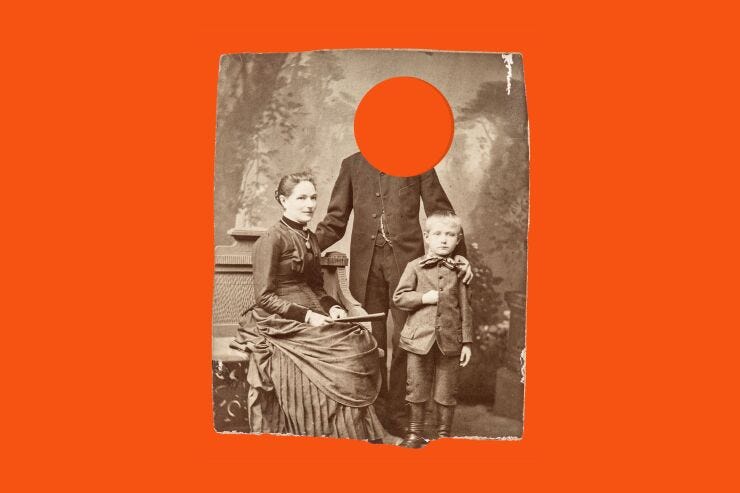

Last January, I reflected on this tension in an essay for U.S. Catholic about how my family estrangement affects my holiday season. This topic is, of course, intensely personal for me. I’ve only ever shared bits of my story online, such as here:

I’m not sure if I’ll ever share the entire story. (Today won’t be the day when I tell-all.) But I do want to take a moment to offer consolation to those of you who, like me, experience the acute loss of family separation and find yourselves alone during the holidays.

I know I’m not the only one. I’ve heard readers’ stories of abuse (emotional, sexual, spiritual), of dysfunction and disappointment, and of distance from those with whom you share genes.

In fact, even those of you who do head home during this “happ-happiest season of all” experience the pain of missed expectations and faulty communication.

No one’s family-of-origin is simple.

I have seen Millennials and Gen-Xers struggle with their Baby Boomer parents. I have seen Baby Boomers struggle with their Silent Gen parents. I have seen Gen Zers struggle with their Gen X parents.

The struggle between adult children and their parents is universal. But estrangement isn’t.

When I first cut the cord with my parents, I felt overwhelming guilt. I felt I had “given up,” that I hadn’t been strong enough to hold the relationship together anymore. Why hadn’t I been able to “get over it,” as so many of my peers seemed able to do? Why couldn’t I overlook the failures of my parents by avoiding the tough topics and getting by with the barest relationship? Why was I so being so difficult? (Did I mention I was profoundly enmeshed with my parents?!)

Yet by that point in 2016 when I stopped returning their calls, emails, texts, comments and direct messages, I had already spent years striving to heal a problem that was not mine alone to solve. I had assumed that if I had just one more conversation, my parents would finally apologize or change or accept my boundaries and personhood. Instead, I was only acting as a textbook codependent does.

Therapy was what broke the cycle. I spent almost a decade in therapy during my 20s. During that time, I had watched my relationship with my parents deteriorate. At first this troubled and confused me. How was it that my healing was worsening our relationship? I grew to understand, however, that as I became healthier, I no longer accepted the old rules of engagement, which, naturally, frustrated my parents who wanted our relationship to stay the same. In their view, my experimental boundaries, individuated desires and pursuits, and distinct voice threatened our relationship. Therapy made me less obliging. And as my parents reacted poorly to these changes in me, I began to pull back.

I set one boundary, and then one hundred more. Finally, after my parents bullishly ignored the fence posts I’d carefully erected between us, I laid the final, immovable boundary: a brick wall. In July 2016, we stopped talking.

Though I understood that to be the only next step left to me, the decision to initiate estrangement—and to continue it—was agonizing. It remained agonizing for years.

Part of my agony was plain old grief.

No surprise, the holidays were the worst time of year. I missed my family-of-origin viscerally—the foods we used to eat, the holiday albums that made up our soundtrack, the games and movies we played and watched, the way it felt to wake up to a full house. I did not miss, however, the anxiety and confusion and hurt that would accompany me through each interaction with my family-of-origin. So, though I grieved, I also understood that I felt psychologically safe for the first time. That safety allowed me to start over with my husband and our children. We invited friends over for the holidays and developed our own rhythms. Slowly, I was rebuilt.

But there was another aspect to my agony: I worried I was disappointing Jesus. That, despite my careful decision-making, my accountability to others, my slowness in coming to the boundary, Jesus would not approve.

And I cared so much about Jesus, who I considered a sort of big brother I’d never had and always wanted. As a firstborn, I wanted to do what was right. I wanted God to be proud of me even as my parents’ pride in me evaporated.

Church people sometimes made this fear worse, perhaps unwittingly.

It took time, but eventually I discovered that my assumptions about Jesus were wrong. He did not value unity about truth, above my wellbeing.

In fact, as I studied the Bible, I came to understand many of Jesus’s actions through the lens of individuation from his family-of-origin.

First, Jesus’s family relationships were always unusual. Joseph was the stepparent, and Mary carried to term the offspring of God, conceived outside of marriage. Talk about an unusual first-century family system.

And then, as he aged, Jesus began to set boundaries and individuate from his parents, as any teenager and adult would have.

Remember when Jesus, as a 12-year-old, stays in Jerusalem while his parents leave and then frantically search for him? He justifies himself in the only way that makes sense: he was in his father’s house. Not in Joseph’s care, but in God’s. Jesus is making it clear that his path may lead him away from his family, even at that early age.

Now, consider the moment when Jesus is teaching and his family members arrive to take him home. Mary and Jesus’s siblings must have been experiencing their son as a great embarrassment—he was running around claiming to be Messiah! Their Jesus? Please!

In that painful moment, Jesus’s family members seek to check Jesus’s actions. They ask to speak with him in private (code for “you’re in trouble”), and Jesus does not oblige. In fact, Jesus’s words put them in their place. He says to the crowd, “Who are my mother and my brothers? Whoever does the will of God, they are my brother and sister and mother” (Matt. 12:48, 50, NIV). In other words, “Back up, family; I have work to do that has nothing to do with you.” Then Jesus went on preaching, unfazed by his family’s disapproval.

In Hebrew culture, family ties made up a person’s only significant identity. From immediate family members, a child an inherited his trade, financial stability, a place to live, and relational standing in the wider community. So, Jesus’s response in Matthew 12 would have sounded like disowning his family-of-origin and rejecting the familial role placed upon him as oldest brother.

Perhaps this makes sense of Jesus’s earlier word: “Do not suppose that I have come to bring peace on the earth; I did not come to bring peace, but a sword” (Matt. 10:34, NIV).

What kind of conflict does Jesus say he’ll bring to those who follow him? The most intimate severing of relationship: “…I have come to turn ‘a man against his father, a daughter against her mother, a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law—a man’s enemies will be the members of his own household’” (Matt. 10:35–36, NIV).

These words are certainly a threat, but they are also a pronouncement of grief. Jesus understands how offensive his life and death will be because Jesus experienced the conflict and pain of family estrangement personally.

Yet though Jesus clearly did not shy away from family conflict, Jesus is not merely a rebellious teenager.

In fact, Jesus models both healthy conflict and restoration between disagreeing relatives.

As Jesus hung on the cross, he matched his disciple John with his mother Mary, asking him to provide for her in Jesus’s absence. Even as he was dying, Jesus fulfilled his role as provider for his dependent family members.

And remember Jesus’ brother James? He was likely the one sent to collect his embarrassing older brother during the incident of Matthew 12. But James eventually changed his tune. After Jesus’s death and resurrection, James led the Christian Jerusalem church, eventually suffering martyrdom as he followed his big brother’s example.

Also Jesus’s mother, Mary, demonstrates a shift in her thinking about her son by sharing stories of Jesus’s early life with the Gospel writers. Her testimony— “treasured up in her heart” (Luke 2:19)—is what proves Jesus’s miraculous origins and affirming his divinity (through the story of immaculate conception).

Mary and James both came to see Jesus through his terms, his distinctive identity, and they relinquished their ideas about who he used to be while taking Jesus’s self-defining words about himself to heart. They accept that Jesus, their son and brother, is God. (Truly wild.)

This restoration is a beautiful end to Jesus’s story. But, of course, Jesus did not experience the full about-face during his lifetime.

Which is one way of saying, family estrangement usually does not have a quick fix. It is painful and lonely and normative. And it’s not the whole story.

Jesus understands family estrangement and he did not force a fix. He allows the disagreement between himself and his family members to persist. And he makes space for resolution, too. He is our example.

As Christ followers, we must make space for both conflict and its resolution.

We hold both the reality of our present pain and the future possibility of comfort.

We cultivate tenderness toward all parties involved.

We love both the perpetrator and victim of abuse.

We offer comfort to the instigator and bystander in a conflict.

We relish and protect our individuated space and health, and we seek ways to love and serve others selflessly (even and especially those who have harmed us).

Remember that on each side of every conflict stands a human being whom God dearly loves.

Psychological health and healing is not quick in coming. It is not guaranteed within the span of our brief lifetimes. But restoration is not out of reach, and it is not impossible.

By the mercy of God, the proud will be humbled, and the humble will be elevated. By the mercy of God, the voices of victims will be believed, and the perpetrators will make amends. By the mercy of God, heaven will be full to the brim with all of us, guilty and innocent alike.

In the meantime, though, as you interact with family members both healed and unhealed during this holiday season, I urge you to move gently, take walks and deep breaths, say sorry when you lose it, and ask for those eight to twelve long hugs a day we each require to be well.

And I’ll be doing the same over here. :)

Because it’s okay to be human.

Thanks for reading, my friends! I’ll be taking a Christmas break, so you’ll hear from me again in the New Year. :)

On behalf of myself and the thousands of other who come from homes where abuse and dysfunction are part of the hidden narrative, thank you. I remember the first Christmas my siblings and I had together after my parents passed, it felt like we could breathe for the first time, and actually celebrate together. Every other holiday up to then had been about "managing," whether that meant our parents, our kids, our extended families, or ourselves. Godspeed to you as you find your holiday rhythm this year in whatever way brings you joy.