the Empathy List #110: When Other People Wreck God's Plan for Your Life

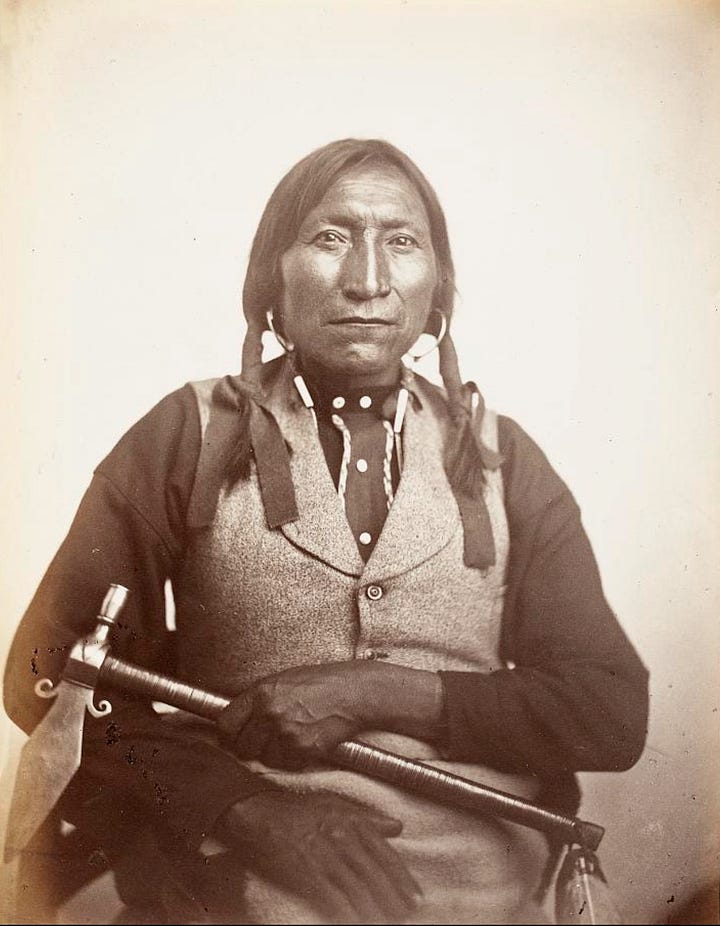

Isabel Crawford, Deaf Missionary to the Kiowa Tribe, Died Bitter toward her Own Denomination

Hello friend, Liz here.

I wrote an essay this past summer about my very favorite missionary, a deaf white Baptist lady who centered her life on one indigenous community in Oklahoma.

She ministered to two Kiowa tribes, proselytizing with unusual respect and cultural sensitivity even though she lived through an age of American exceptionalism known as “Manifest Destiny.”

Once she left the mission “field” (as missionaries call their assignments), she campaigned tirelessly for indigenous rights in the U.S., preaching from Baptist pulpits that the real “American Indian problem” was not “the Indians” but “the white man.” (Direct quotes there.) Talk about a fire ball!!

The tone of the essay I published was, mostly, triumphant. Because Isabel Crawford is an example to me.

Despite the misogyny she faced within her denomination, despite racism toward those she served from her government and the Christian church, despite the fact that her paycheck depended upon Baptist communities to keep donating funds so she could do her work (!), she did not allow the gospel of Jesus to become sullied by her own white supremacist culture.

The major point: their struggles were hers.

She had been invited personally by a particular Kiowa leader, Chief Domot, arriving in March 1896. Over the next ten years, Crawford’s day-to-day ministry was quotidian—cleaning, cooking, hosting, praying for and with tribe members, reading the Bible with them. But there were notable moments, such as the constant refrain of death within the tribe. She spent much time sewing quilts by hand for sick children, crafting coffins, and presiding over funerals.

One particular exchange of shared grief moved me during my research.

Chief Domot’s child died in the summer of 1897, during one of Crawford’s furloughs. When she returned and heard the news, Crawford wrote,

“Domot, the father, called with hair all cut and lips quivering. Dropping his head gently upon my shoulder he wept silently for some time and then signed: ‘My little girl is dead. Jesus has carried her up. I have lost many children and have always been afraid when they died. This time I’m not afraid. You have told me the true road. I know now that my little ones are with Jesus. He knows what is best. I am not afraid but my heart cries.”

While Crawford initially grieved with Domot and his wife, her grief would turn personal. Within a few weeks of returning to the tribe, she received news that her own mother had passed away. In her journal, she described how the tribe, and especially Chief Domot, comforted her in the days following:

“Coming sadly out of my tent this morning I was surrounded by a number of old Indian men wrapped in faded blankets. They had laid aside their bright colors to show sympathy in their own way. Placing a brown arm about me and pressing my aching head upon his shoulder (as he had placed his own on mine the very day my mother died [the day he told me of his daughter’s death]) Domot prayed while the others cried aloud. ‘O Great Spirit! Our leetle [sic] Jesus woman has lost her mother and her heart is all broken to pieces. Gather it together again and put it back strong. You have given her to us now and we will take the best care of her we know how.’

How I cried! …Sob followed sob and the climax of misery was reached when I felt Domot’s warm tears falling down on my cheek and neck. …Then wonder of wonders! Into my heart there crept gently, silently, sweetly, a perfect calm. Tears ceased, a big sigh escaped and love was born. A love for the Indians not my own.”

After that, whenever she mentioned Chief Domot, she would refer to him as “the Indian who pressed my aching head upon his shoulder when my mother died and prayed [for me] with the tears streaming down his paint face!”

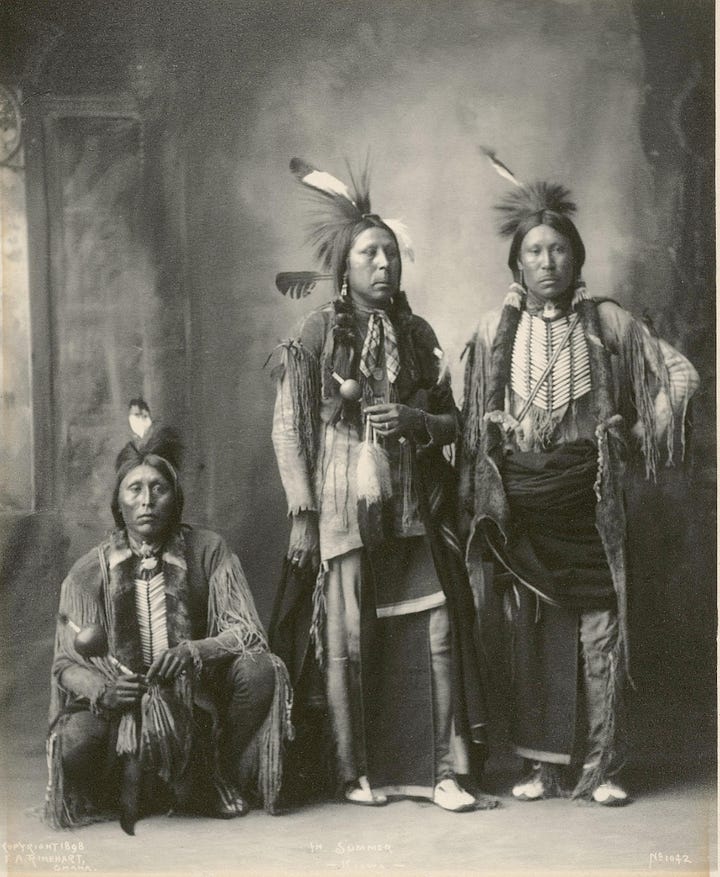

This egalitarian exchange of care between Crawford and the tribe resulted in the conversions of over 30 Kiowa to Christianity. They did not call it the white man’s religion or even by its universal name of Christianity; instead, the Kiowa called it the “Jesus Way.”

Crawford saw herself (and acted) as their sister, not their spiritual mother, and she considered these new believers her brothers and sisters. They were on one spiritual plane, no one above or below, all under the authority of God alone.

As she once put it, “We are not here to boss the Indians [as missionaries], but to do what they let us when it is not wrong. [Even] if they are not ‘citizens’ on earth they are citizens of heaven and no person has a right to domineer over them.”1

Crawford’s biographer, Marilyn Färdig Whiteley, told me in an interview that the central tenant of Crawford’s ministry was to cultivate independence and spiritual autonomy among the people she served. Whiteley said, “…It was so important to [Crawford] that these people, as they developed toward becoming a church, that they be independent.” And it resulted in an exceptional ministry.

However, there was a darker side to Crawford’s story that I did not have space to include in my brief 2,000-word narrative.

And I want to share it with you today because I find it both instructive and humanizing for any of us who are struggling with the religious institutions we’re a part of.

Because Isabel Crawford also struggled with her Christian institutions.

She carried a deep bitterness inside her toward her denomination and sending institution because of a conflict that removed her from the Kiowa tribe. In fact, she once wrote that she believed the institution that had sent her onto the mission field had thwarted the plan of God for her life

She wrote that she had been “crushed in the denominational machinery and God’s plan for my life completely wrecked!”

I believe Isabel Crawford’s disillusionment has something to teach us about living a life of devoted advocacy.

Here’s what happened:

While Crawford’s commitment to Kiowa independence was not shared by her denomination, she might have flown under the radar if not for the incident of the “Jesus Eat.”

The conflict began innocently. After years of saving up, the Saddle Mountain congregation erected a church building for themselves. To celebrate, they requested that the denomination provide a way for them to receive communion—which the Kiowa called the “Jesus Eat”—once-a-month, as was the Baptist’s custom at the time.

As a non-ordained female, Crawford could not herself distribute the sacrament… because only ordained white males had the denomination’s permission to do so. The problem was, no other ordained male ministers worked on mission alongside Crawford. This left the worshippers in a bind. How to obey God and remember Jesus through communion if they had no one to “rightly” administer it?

To her credit, Crawford did try to comply with the denomination’s rules. She began arranging monthly visits from nearby male Baptist ministers. But these ministers often had their own congregations and very little extra capacity to devote to her community. Added to that, the journey to Saddle Mountain was not easy, requiring visitors to cross twenty miles over a mountain pass to reach the Kiowa congregation.

On this particular Sunday in September 1903, the visiting minister that Crawford had invited to preside over the sacrament cancelled at the last minute. So, rather than go without, the pragmatic Crawford asked the congregation to elect one of their own to administer the bread and wine for the service. They picked their deacon, Lucius Aitsan, a man who would eventually become the first ordained native pastor of the church.

Crawford describes the communion service as a moving affair, writing that the community worshipped “with so much tenderness of feeling that tears rolled down many cheeks and ten dollars was given to Jesus as a thank offering…”

But not everyone felt warm fuzzies about the church’s decision to break Baptist rules.

Whiteley explained, “…[Crawford] felt so strongly that this was proper Baptist procedure, that the sacrament belonged to the church, not to the clergy. It belonged the congregation, not to the clergy…And that’s a good strong Baptist principle, but it didn’t exactly fit with the hierarchy, let’s say.”

And the hierarchy did not approve. They disapproved strongly, especially the Southern Baptists.2

Luke Eric Lassiter describes the fall-out in his book The Jesus Road: Kiowas, Christianity and Indian Hymns (co-authored by Clyde Ellis and Ralph Kotay):

“Because only white, male, ordained ministers could serve communion, the church’s decision—which Crawford openly and vocally supported—led to so serious a breach with the American Baptist Home Mission Society [the all-male counterpoint to the Women’s mission] that the church was formally reprimanded, and Crawford… forced out.”

Though Crawford’s allies and mentors ultimately agreed that she’d made the right choice in orchestrating the communion service, any of the Northern Baptists that were on her side seemed wary of inciting further conflict with their Southern Baptist brethren so close on the heels of the Civil War.

For months, she corresponded with allies, detractors, and multiple Baptist missionary societies, trying her damndest to resolve what she believed was a big misunderstanding.

No dice. Even the Baptists who took her side ultimately decided to err on the side of “unity.” In this case, “unity” meant conceding to the most conservative pastors, allowing the Saddle Mountain church and their missionary to take the rap.

Furious and feeling abandoned, Crawford left her beloved Kiowa congregation in 1906, resigning from her post at the advice of the Baptist women’s missions agency. (And they offered her a new assignment).

But first, she checked herself into a sanitorium in 1907 in order to recover both physically and psychologically from the conflict, which had taken a toll on her already-fragile health.

When she considered the conflict later, Crawford blamed her gender and the egos of the male missionaries with whom she’d fought, saying her “chief offence [sic] had been that she was a woman under the Women’s Society.”

The offending pastors had their own take. Twenty years later, one characterized Crawford in a letter to the current pastor the Saddle Mountain church as particularly contentious, writing, “You think that you could get along with Miss Crawford. Then you could do something that no one else has EVER been able to do—man or woman.”

However, she did eventually make peace with the decision to move away from the Kiowa of Oklahoma—at least temporarily.

In her absence, however, the church shrunk, a fact that pained her. And the Kiowa themselves never stopped asking her to return. They, like Crawford, resented the interference of the male mission board, which did not treat them with the same respect as Crawford and her female counterparts who had also arrived from the women’s missionary board.

So Crawford continued to visit as often as she was allowed. And she harbored a dream of returning. Which is why, twenty years later, she jumped at the chance to move back.

By 1929, a new white male Baptist minister was leading the Saddle Mountain congregation, a man who held Crawford in high regard. So, he invited her to return after her retirement. He wrote to her mission board on her behalf, asking that they allow her “to stay as long as she lives” and requesting that they offer her “land on which to build a house.”

But the older male Baptists in the region had long memories.

Those who had opposed her in the earlier conflict again wrote to all interested parties and opposed her presence twenty years later, calling her “dangerous” and her interference “unwise,” fearing further conflict with the tribe and the denomination. And the Women’s American Baptist Home Mission Society, Crawford’s senders, heeded the words of these men. They barred Crawford from returning, even after her retirement.

Crawford never got over that.

When she received their decision, she wrote back immediately: “Believing, without the shadow of a doubt, that God’s plan for my life has been wrecked the second time, because of the non-co-operation of our two Home Mission Boards [both the men and women’s boards], I hereby present my resignation…”

Though she would live into her mid-nineties, she never did return to Oklahoma to stay except in death. She was buried amongst the Kiowa in their graveyard. She’d been offered a plot by the tribe members decades earlier, and they requested she inscribe these words on her tombstone: “I dwell among mine own people.” To this day, her remains lie among the men and women she converted way back then, finally reunited with the tribe she loved in her death.

Question: Can other people “wreck” God’s plan for our lives?

Can God’s plan be thwarted in the way Crawford alleges?

I used to think no, that’s impossible. If God made the cosmos, then surely our puny human decisions cannot shift the actions of Divinity. But now, I’m less certain.

While I have seen God interfere dramatically in the natural processes of my life, more often, I have witnessed God’s restraint. I have experienced God’s influence as a soft-touch.

Humans have much more autonomy than we feel comfortable admitting.

Isn’t it easier to say that God holds the whole world in God’s hands rather than to say that the fossil fuels that you and I have processed and become addicted to may actually destroy the planet that God has made… and that God may let it happen?

However, if there’s one thing that my study of Genesis has taught me, it’s that God is more committed to the concept of freewill than I am.

Sometimes, God stays out of things, even when we want God to intervene.

Sometimes, God lets God’s creatures do terrible harm to each other.

Sometimes, we cannot explain why God allows these things, and sometimes, it feels like God’s distance is an evil in itself.

I have no answers to share. But I do have a single consolation: death is not the end. There is a life past this one, and that life will be good. Beyond that, who can make sense of the mystery of pain?

Here’s what I’m getting at: while I cannot say for certain whether I agree with Crawford’s assertion, I do relate to her.

Her visceral discomfort and pain in being “thrown under the bus” is familiar to me as a female at church.

Sometimes, I too feel that the fact I was born female is unforgivable to male Christians.

Being female can feel like a fatal flaw. Because who I am—the gifts I possess in my personality via nature and nurture—do not match up with the norms conservative evangelicalism sets out for my gender.

My fatal flaw: I am a former class president, an unabashed thinker and straight-A student, an articulate and unafraid public speaker, a pastoral mother hen who has devoted herself to God and God’s church… and unfortunately, I am female.

If I had been born male with this list of characteristics, wouldn’t I have been shuttled down the seminary track post haste? Wouldn’t I have been handed leadership positions, paychecks, and power—likely before I knew how to wield them? Wouldn’t I have had opportunities that still, to this day, have been denied to me and so many other women?

I would like to say that this conclusion is up for debate, but I know my people and my culture too well.

For example: Mark Driscoll founded an entire church planting network without a seminary degree in his early twenties with mentorship and funding from one of the largest and richest denominations in the world. That’s the model.

That’s the way evangelicalism has been so successful: move fast, break people. And then maybe, if your donors demand it, fix what broke… or not.

What I mean to say is, I understand this vortex of bitterness that Crawford suffered.

Because I, too, have found myself engulfed (at times) in the anger of feeling “wrong” for the natural characteristics and convictions I possess. I have known the resentment and rage at a culture that disallows me from expressing the full extent of my humanity. And sometimes I’ve felt that the same rigid misogyny that devalued my gifts has also delayed or thwarted me.

I am tempted to wonder, have I missed the chance to do the unique work I was made to do—the unique person I was made to be—because I initially accepted those faulty norms of my gender and religion?

I feel rage for myself, a self-pity. But I also feel a righteous anger at the abuse institutions have rubber-stamped through empowering evil men whose work has harmed so many people—especially women, especially queer people, especially BIPOC, especially all of us other folks without influence and education and wealth that would grant us automatic access to “a seat at the table.”

Sometimes I’ve felt that I’m not even allowed access to the room as the table where the important people sit.

But I have found a way out of these feelings. The self-pity, regret and rage is only grief in another form.

Is it wrong to be disappointed? Nope. Is it wrong to be consumed by disappointment? Yes, I think so. Our bitterness is destructive, but not in the way we expect.

When we cultivate bitterness, we willingly hand over our power to our pain. We drag a boulder behind us, forever burdened by the weight of the past and unable to let it go. But we still have the power to decide how we will spend our energies and emotions. We can release the pain. We can learn from it. And we can let it go.

This is the power of forgiveness toward ourselves and also toward those who have harmed us.

Forgiveness is a singular pursuit, a thing performed between one woman and her Creator. (Reconciliation takes two; forgiveness takes one.) Which means it doesn’t matter if you ever get an apology, you can experience freedom from the pain that has defined your past.

How has institutional disappointment affected the way you see God and/or yourself?

This is the reason I’m telling you Isabel Crawford’s story.

Did the people who hurt her wreck God’s plan for her life? I cannot say for sure. But I do have the luxury of viewing her life from above. I get to weigh the entire span of Isabel Crawford’s lifetime, a vision that few of us gain when we’re experiencing one day at a time.

Here’s what I see in the span of Crawford’s life: Yes, she was hurt. Yes, she was kept from the tribe for the rest of her life, trapped in grief and bitterness. Yes, the congregation she founded closed.

But her separation from the tribe had the effect of forcing her up and out. I would suggest that God moved her away from the tribe for the sake of the tribe.

Crawford influenced a generation of missionaries after her by forcefully speaking the truth about the injustice perpetuated against native nations and peoples. Late in her life, the next generation of ministers told her they remembered her, that her tenderness toward indigenous peoples had made a lasting impression on them.

Crawford joined advocacy organizations, organizations that greatly influenced how the U.S. government treated Native Americans. Her advocacy shifted laws toward justice, and she had the opportunity to participate in policy change toward native peoples.

Crawford also wrote multiple books from her journals. Her stories humanized indigenous peoples, offering their stories as beautiful and worthy to a culture unwilling to witness their glory. She forced her culture to see them as beautiful and worthy anyway.

In short, Isabel Crawford became an unwilling prophet to the American people, especially to the Baptist churches of North America. Even if she would not have chosen that path, her life was still spent for the good of the Kiowa people she loved. She continued her ministry to the Kiowa—even from a distance.

We do not have to carry our pain forever, friends.

We do not forgive for the sake of the other person, the one who harmed us, but for our own selves, for our own freedom. Personally, I do not want to be replaying the same harms that occurred in my twenties when I hit age ninety-six.

Life, God, and these cosmos are just too big to get stuck; I want a bigger vision. So, I choose to move on. Today is a day to move forward toward truth and justice. Today is new.

Thanks for reading, my friends!

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

P.S. In honor of Indigenous Peoples’ Day, I’m removing the paywall from this essay I wrote about how indigenous peoples’ day (formerly known as Columbus Day) is a chance to repent. I hope you enjoy!

Notes

She published these words from her journal in her 1915 autobiography, Kiowa: A Woman Missionary in Indian Territory.

Isabel Crawford had been sent to the Kiowa by the women’s mission of the Northern Baptists. However, the Baptist denomination included both a Northern and Southern contingent, and they had almost split due to the Civil War conflict. In Oklahoma, Crawford was surrounded by Southern Baptist male ministers and missionaries with strong opinions about both native peoples and females at church… which only exacerbated the conflict.

Oh friend, you know I relate to the disappointment and bitterness. I pray we can continue to heal and find our way though it has not been supported by others because we are women.

Really appreciate this Charlotte. Thank you for introducing me to this amazing woman.