the Empathy List #143: Where Do You Get Your Ideas?

Episode 1 of the podcast series, Knock at the Sky: A Creative Journey, in which Jeremy and I discuss beginnings.

Hello friend, Liz here.

Today, the first episode of Knock at the Sky: A Creative Journey is live, and you can listen in your podcast app of choice.

Jeremy and I are talking all about ideas and beginnings.

Where do artistic ideas come from? How do you begin a project? How do you decide when you have a good idea, good enough to spend more time on? And then, after you’ve settled on an idea, how do you find the form the work will take? In other words, how do you start making?

We also discuss a preoccupation of ours: the question of “voice” and “style”. How do you develop the writing voice and/or artistic style that makes a work unique to you amid this crowded landscape of makers?

We get specific about how the book project, Knock at the Sky, came into being, including the early discussions between Jeremy and I about collaboration.

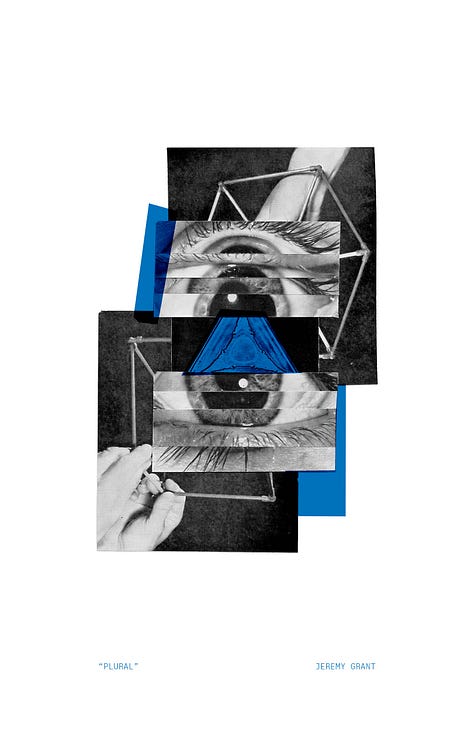

We’re also discussing the fine art collages that precede chapters 1, 2, and 3—first, I tell you what I see and guess at the meaning behind the paper, and then, Jeremy tells me what each collage really means. I enjoyed this segment so much! I hope our discussions make the art come alive for you, too.

Subscribe and/or listen here—

Apple Podcasts / iHeart Radio / Spotify / Amazon Music and Audible / Stitcher

Below you’ll find an edited transcript of our conversation, for anyone who prefers that kind of thing.

Thanks for reading and/or listening, my friends! Now, let’s get creating!

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

THE PODCAST—

Knock at the Sky: A Creative Journey

Episode 1: Ideas

What is Knock at the Sky about? Why did you write it?

JEREMY: Before we get into the idea of ideas, and how you develop and cultivate an idea, I think it'll be helpful for listeners to get a little bit of context about the book in general. Liz, maybe give it like the top line: what is Knock at the Sky about? Why did you write it?

LIZ: The book is called Knock at the Sky: Seeking God in Genesis After Losing Faith in the Bible. And I am a post-evangelical, 30-something. I grew up within White, American Evangelicalism and upon coming out of it and into a liberatory Mainline expression of Christianity, I had a lot of questions about how to approach the Bible again.

A lot of people I knew [who had deconstructed] just wanted to stuff the Bible down their sink garbage disposal. They were done with the Bible, did not want anything to do with it. And frankly, I don't blame those people, I completely understand why someone would be done with the Bible. After all it's been used, especially the Book of Genesis, has been used as one of the most lethal weapons in the culture wars. So [Genesis] has been very much used by American evangelicalism against all sorts of people.

But I have a lot of questions about the origins of humanity and how the Bible fits into that story. I wanted to reencounter God through the lens of the first encounters described in Genesis. So, my book is a sequential reading of the Book of Genesis but then I also braid in a lot of other stories alongside as a way of trying to engage more broadly, more artfully with this ancient text. And my hope is that somebody even outside of the Christian faith could find something beautiful here that would resonate about our Origins as human beings.

JEREMY: You and I have talked a lot about ekphrastic works—art about art. And that’s your approach in Knock at the Sky. You're engaging with Scripture as a work of art, as one of the cornerstone pieces of literature in human history, and [you’re] seeing what that engagement inspires within you. You engage with [Genesis] in like a linear way, through the book of Genesis chapter by chapter. But then also, [you’re asking], what else does that inspire [in me]? You’re also bringing in a diversity of science writing and storytelling about adventurers and explorers…

LIZ: …archaeologists, fine art criticism…

JEREMY: …theologians who [are] outside of the mainstream. So…it's a book that sort of defies categorization and is, therefore, hard to succinctly describe. [Laughs]

LIZ: [Laughs] Guys, we did this take like four times, just trying to describe this damn book.

Where do you get your ideas?

JEREMY: So today we're talking about ideas, the idea of ideas, how do you get an idea? …At every reading writers do,… someone [inevitably] asks, where do you get your ideas? My artistic practice is collage. I also work in assemblage, animation, design, illustration. For you, [your medium is] writing—which can also be a bit of a collage-like process. If someone asks you where you get your ideas, what do you say?

LIZ: My process begins with questions. …Because a lot of [my work] is research-based, a lot of [my ideas] come [from] hearing a story somewhere that I find interesting and that I want to get to the bottom of. In the first chapter of the book, I write about whale song[, for example]. …I had heard an episode on Radiolab and I got really inspired and started digging. That's kind of a classic inspiration story: I hear the story from somebody else and I want to find [out more about] it. But one of the things that I do is to try to tell stories in a way that you haven't heard before.

So, I [became] curious about how whale song actually works [which Radiolab did not discuss]. Like, why do whales sing? [Turns out,] whale song is a bellow in their guts.

JEREMY: It's all internally self-contained in their bodies. Because for us, vocalization and singing requires the expulsion of air…

LIZ: out of a throat.

JEREMY: Whales are not doing that [because]… they are coming to the surface for breath.

LIZ: Yeah, they recycle air within their own guts.

JEREMY: So, there's like a very distinct way that [whales] are vocalizing.

LIZ: But nobody knows why they vocalize. So there is still this ongoing question.

JEREMY: So, those are the kind of questions. Starts with a question for you, and then you try to go deeper with it.

LIZ: It really animates me to keep digging to find the original source, to find the kernel of story, the person at the center of it. For me, [writing] really is about curiosity. It really is about getting to the bottom.

JEREMY: Would you say that [your practice is] less about having a clear idea of where you're going, and more about following the threads of curiosity and letting the ideas emerge?

LIZ: Absolutely.

JEREMY: You may have a big picture theme [like,] “I want to explore Genesis, and I want to explore origins,” but to do that, you actually end up exploring a lot more. You go a lot deeper into a lot of different subjects.

LIZ: So you know, the reason I ended up writing about Genesis anyway is because …I became really obsessed with the idea of God's voice. Where does God's voice come from? You know, normally people vocalize [by] expel[ling] air from their lungs. Their voice has a container—a throat, lips, teeth. Which both describes the origin of the voice and the intention. That's how voices work in humans. But God, at the beginning of the world, speaks with a voice without a container, and then speaks all of the cosmos into existence. So, I started writing about that, and I just happened to be at this phenomenal residency, which sounds like a humble brag and …I was astonished to get to be there. I got to work with a phenomenal writer, and he would reread my pages from the day,… and give me feedback. And he loved this. He said, Liz, this is really captivating me. And I started to share some of these ideas with early readers and I saw that was a spark there.

You know, I never would have written about Genesis [if I hadn’t been encouraged to do it]. I mean, [every Chrisitian author] writes about Genesis. I mean Madeleine L'engle,… Marilynne Robinson just came out with a book. Like, who needs my [perspective on Genesis]?

JEREMY: You were almost done with your book when Robinson’s work came out, and you were like, “Oh, shoot, okay, well…”

LIZ: “…I guess I need to throw away my book now since a Pulitzer Prize winner beat me to it.”

JEREMY: There's something that I think you're going for here, and I appreciate it: the idea is not the reason for the work. The idea is the result of the work. You're not approaching this with an agenda already. [Like,] I want to prove that the Earth is 6,000-years-old. Therefore, I'm going to read Genesis in a particular way so that, I [can prove…]

LIZ: Excuse, me, it is. You heretic. Just kidding, I believe in evolution, I'm sorry.

JEREMY: But you're coming into this and saying, I'm compelled to engage with this idea of origins, and God's voice, and these earliest stories of [hu]mankind. I'm compelled to engage with this, and I'm going to follow that wherever it goes. I'm gonna follow it deeply into these rabbit trails and these artistic forays. And then you're going to somehow pull all of that back together and braid it together into something that becomes an idea, something that becomes a narrative and a form.

LIZ: I mean, the jury is still out on whether that works.

JEREMY: …So, let us know in the comments.

LIZ: Yeah, let us know how much I failed…

How do you decide on the form your art will take?

JEREMY: This might transition us [because] we had a note [in our notes] about defining the parameters of a project and figuring out the form of a project. Talk to us about what that looks like for you. So you explore deeply, all these rabbit trails, and it sounds like you end up with a pallete. You end up with a spread of source materials—whether that’s little essays, or research—and then, almost in a collage-like process, you start to put those pieces back together, say[ing] what happens when I put this story next to this story? And what does that teach me? You want to talk to me a little bit about that?

LIZ: I mean, it's kind of a mess. It's like associative finger painting. It just feels like you throw things at the wall and see what happens when you put them next to each other.

I mean, how does that work for you with collage? What is that process like on your end?

JEREMY: My work begins with like palette building. So, maybe the idea isn't there yet but… in this case, I'm creating responsively to your work. I had access to early drafts. You would tell me about what you were thinking about, so I even heard some of the ideas before it went into the work. But I was creating in response to your work, just as you're creating work that responding to this older, ancient work of art.

But the first thing I did was like build palettes. So I had to figure out, what is my source material? You had source material like the desert fathers and mothers, these fringe prophetic voices, and science, and turn-of-the-century explorers.

My sources were collage materials, right? And we found there was a restraint: we're going to print [the book] in black and white, so I need to work in black and white, so I [decided], let me work with black-and-white imagery to begin with. So I was looking at old Life magazines and vintage sources. So, I have themes I'm going to work around, then I started to build a palette. Then I find my materials. And for me, the idea emerges through a process of working.

I definitely found some conceptual overlap between a Life magazine and like an Audubon photo book about the oceans. The Life magazines were this cultural monolith of mid-century white America. And this thrust of modernism at the time was looking to condense everything into nice neat systems that you could explain and rationalize,… to our detriment. And I [noticed that] you and I had some like thematic overlap—where theologically, you’re talking about a condensing and compressing, looking for conformity and that sort of monoculture Utopia that was being presented at the time. Everything was shiny chrome cars in those old Life magazines.

I found that interesting because at the same time, you were stripping away some of the layers of scriptural interpretation, and I was saying, let's pull apart and cut apart and tear apart these sort of modernist era relics, cutting them into smaller pieces and rearranging [so that they] speak into these themes of first contact.

LIZ: I resonate with that. First contact became a very interesting metaphor for me. What does it look like to approach [the Bible] without some of the cultural lenses that I come with, as a white American 30-something female? …What does it feel like to read these [stories in Genesis] as if I haven't read them a hundred million times before… in my Adventures in Odyssey Bible. Which I definitely had.

JEREMY: Deep cut Evangelical Christian reference right there.

LIZ: But what’s interesting is, both you and I were [trying to] capture this optimism [of modernism], too. So much of American Evangelical theology about the Book of Genesis was centered around an optimism that we could grasp certainty. We could theologically put it all in a box, it would all fit, and there would be no questions left. But this ancient work is 4,000 years old [in some parts]. It is just unrealistic to believe that we can put the entire thing in a box, that would be appropriate and understandable and relevant to our era, and our people in our culture. So, you and I both were wrestling with this idea of this theological optimism, this scientific optimism. [Our forebears] really wanted to make everything understandable. But what if it's not?

JEREMY: Collage lends itself to both association and obfuscation. And obfuscation can reveal a source in a different way. So, [you and I are both saying,] let’s make the answer less clear, let's elevate the questions over the answers. So, sometimes collage covers over the subject of an image, and that's actually a way to increase interest—“Why did you cover that person's face with a sticker?” It makes you look at something a second time, or look a little closer. In doing so, we're trying to sidestep those trite answers and quick fixes. Or the modernist era, “We have everything figured out in this tight little theological box.”

LIZ: “It all lines up, it’s so easy, there's just a ‘plain reading.’”

JEREMY: I really like the collage metaphor because for your writing, there is a collage methodology, and the same is true for a lot of creatives, there's a sort of pallet-building [that happens at the start of a project]. Musicians will be sampling sounds and audio recordings in the world, or even recording voice memos to themselves; writers are collecting ideas and writing essays and stories. I'm collecting images and source materials [like magazines]. And then you have to put it all together to figure out, how can I make this cohesive? Or in my case, how do I fit these elements on a page? Along the way you have to make decisions [that limit you]. You have to pick a form.

How do you develop the voice and/or style that makes your work unique to you?

JEREMY: The last thing that we want to discuss is the idea of voice.

LIZ: Well, that's kind of a formal choice itself, yet it's also like a sort of extension of self. It's funny with writing that way. I think with writing voice can be a limitation.

I'm very familiar in my writing. I'm very conversational. I'm not an academic writer. Your personality will come out through the writing. And that's a part of your voice. Many creative nonfiction writers are able to have a more distant tone in their writing, and I have never been that writer. The form I pick also tends to be related to voice. So, if I'm picking to write a braided essay instead of a long narrative nonfiction work…like, we mentioned Marilynne Robinson’s book Reading Genesis earlier, which came out recently and I hear is a very interesting read. But it’s in my TBR, sorry, Marilynne.

JEREMY: It’s on the nightstand beneath a stack of 45 books.

LIZ: Very long TBR.

JEREMY: Liz reads a lot, but…

LIZ: …mostly I buy books.

JEREMY: Yeah, buy books. Buy books, people.

LIZ: So, in [Robinson’s] work, it is narrative nonfiction. It’s sequential and much more digestible than mine in some ways. She's able and willing to go through Genesis like a lecture series. I just don't write that way. It's not how I think. So, I'd rather paste a lot of different things together. So that's part of voice, right? I’m never going to be a Marilynne Robinson. There's no world in which I sound like her. So, that's an obvious limitation.

Also, one of the things that you and I, Jeremy, talked about a lot is, how do we do things in a unique way? In our era of internet connectivity, every story is everywhere, and there does seem to be a stronger sense of cultural Zeitgeist than maybe at other times. There tends to be a homogenizing of culture. I mean, as a writer, I’ve found that the same stories tend to get told and retold.

JEREMY: You mentioned hearing something on Radio Lab and then that inspires you to research a similar subject. You'll get multiple news outlets, and writers, and people inspired by the same things... [And] it’s fine to be inspired by the same thing. But if you're creating the same thing, then your voice is not unique.

Another common question is—this comes up a lot in design and illustration circles—how do you find your style? For writers, specifically, [how do you find] your voice? And that’s where some of the process stuff comes in. You were talking about just going deeper than anybody else. Going further down the trail to discover something that truly shocks you and makes you want to write about it. And then you put that alongside stories you’ve discovered in radically different disciplines, and then you mash those together to see what emerges.

LIZ: I'm incredibly disciplined in making myself return to original source material. That's important to me, too. So, I can hear something, like, here's the general cultural interpretation of a story or character that you’ll find everywhere—on Radio Lab, NPR, whatever. Then if I really get interested, I'm not going to read somebody else's take on that anymore. In fact, I will probably cut myself off from other related takes, because I don't want to copy somebody unintentionally. I don't want to paraphrase or plagiarize, even unintentionally. But I also have realized that part of my own unique voice and interests mean that I will just go deep.

But what does that look like for you? How do you distinguish among the collage artist? What does “voice” look like for collage?

JEREMY: There’s a nuance [between our disciplines] of “voice” versus “style.” The common question for visual artists is, what's your style? What's your aesthetic? And for most artists, the cultivation of a style is dependent upon repetition. It's your “practice.” I like to talk about this as cultivating “your hand.”

So, I use a scalpel in my work. Sometimes, I make cuts with a ruler, a straight cut. Sometimes you can tear materials and you create a ragged edge. But in a lot of my collage, I will be free-hand cutting with a scalpel. And I have developed a particular movement that I have cultivated through repetition, and if I'm making those similar kinds of cuts over and over and over and over again, I may begin to develop “a hand,” a stroke of the brush, or in this case, a scalpel. But I think that looks different for different [mediums].

So for this project, I pursued a few different starts and stops before landing on the aesthetic for these collages. But there are a few things that I leaned into that were both conceptual and felt right for me. I mentioned tearing materials. I don't usually tear a lot of papers by hand, but for this series, it felt like, there's this rift in reality, the torn edge, the little white exposed fibers of the paper feel like a lightning bolt. And there’s a lot of, lightning, powerful divine intervention imagery in Genesis and in your writing, too. There are [also] chopped off faces where you just see part of a face. There [are] torn sheets of paper that feel like a lightning bolt. As these elements took on meaning to me, I then worked them into the style for these collages.

Beyond that, there's an exercise of curation. I created a lot more art than I'm presenting. You do this, I know, you have a million drafts and starts in your writing before it becomes the final work. So you do an exercise of self-curation. Sometimes [another person] speaks into that [curation] process, and sometimes you need to do that for yourself by looking at the work fresh. You say, I’m curating this into a cohesive whole, and that can be an exercise in voice and style as well.

LIZ: Yeah, what we're kind of dancing around is that this project came about—and a lot of art comes about—without an idea. You don’t start with an idea, really. You start with materials. You start with materials and questions, and you start circling them, you get your hands on them, and then you see what comes out of that interaction.

I mean, I think a lot about ideation and inspiration is really about getting your hands dirty.

About Jeremy and Liz

About the Author

Liz Charlotte Grant is an award-winning essayist whose work has been published in The Revealer, Sojourners, Brevity, The Christian Century, Christianity Today, Hippocampus, Religion News Service, US Catholic, National Catholic Review, The Huffington Post, and elsewhere. Her essays have twice won a Jacques Maritain Nonfiction Prize. She also writes The Empathy List, a popular substack that has been recognized by the Webby Awards (‘22, ‘23) and the Associated Church Press Awards (‘23). Knock at the Sky is her first book.

About the Artist

Jeremy Grant is a multi-disciplinary artist whose work is rooted in contrasting modes of natural and mystical experience through a practice that bridges association and obfuscation. He has exhibited work regionally in Colorado since 2008. His 2019 film “Remnants” was exhibited at the Supernova Film Fest, and the Denver Film Festival. He holds degrees in Graphic Design and Illustration (John Brown University, 2007).

[American, b.1985, Monterey Park, CA, USA, based in Denver, CO, USA.]