the Empathy List #144: The Part Where You Sit Your Butt in the Chair

Why does *doing the creative work* have to be so hard?

Hello friend, Liz here.

Today we’re talking about the hard work of sitting your butt in the chair and getting your creative work done.

The 2nd episode of Knock at the Sky: A Creative Journey is live, and you can listen in your podcast app of choice.

Jeremy and I are talking about developing your craft…. by so much practice. And we discuss what it really means for each of us to really sit in the chair and put down a first draft and/or a first pass at a collage. Because making art requires sweat!

We also talk about how our artistic collaboration as a couple worked as we labored over the book, Knock at the Sky. (Spoiler: it did not always go smoothly, but required a lot of communication and boundaries to make things work.)

And we talk about why the practice of art-making is worth it... even if you have less than 1,000 instagram followers and even when you write the shittiest of shitty first drafts. (Like Liz.)

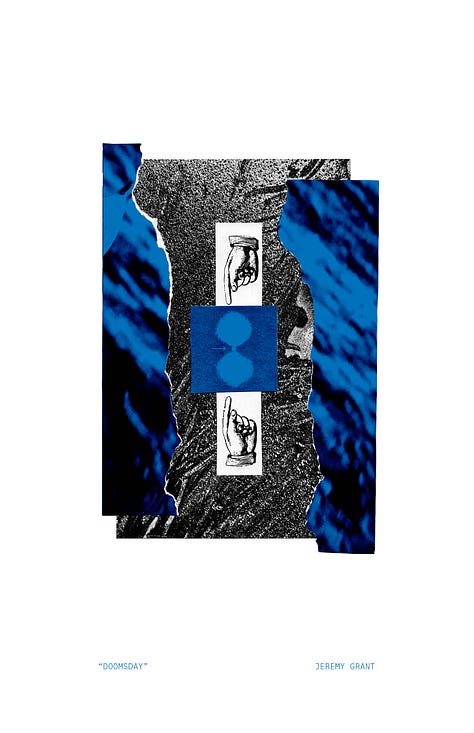

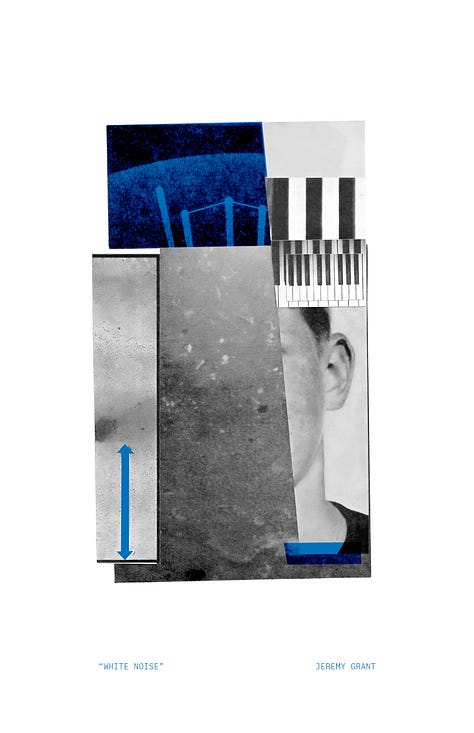

We also discuss the fine art collages that precede Chapters 4, 5, and 6 in the book that has inspired this podcast.

Subscribe and/or listen here—

Apple Podcasts / iHeart Radio / Spotify / Amazon Music and Audible / Stitcher

Below you’ll find an edited transcript of our conversation.

Thanks for reading and/or listening, my friends! Now, let’s get creating!

Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

THE PODCAST—

Knock at the Sky: A Creative Journey, Episode 2: Craft

Embracing the Extra Rough Drafts

JEREMY: So, last episode, we went into the idea of idea. Where do you get your inspiration? How do you find an idea? How do you start a project? This week, we're going to go down the trail and talk about actually completing something. How do you make a first draft? How do you collaborate with an artistic partner?

LIZ: I'm curious, how did you get the first series of collages done? Because there were multiple series, by the way. What did that process look like for you from idea to a completed series?

JEREMY: There's a process of embarking on a creative project where you just have to make a lot of stuff. You just have to show up to the space - and a physical space helps. Whether it's a desk, like you have, or a studio like I have, just showing up and making something without a lot of pressure on the outcome, but just to say, like I'm going to show up in the space, I'm going to make something every day and be patient with it and allow something to emerge.

...I did a lot of exploration early on that were essentially sketches. They were very loose collages that I was just looking to create an atmosphere. And none of those collages ended up in the book. I think one image maybe that I found in that exploration actually made it into the book.

LIZ: Why didn't those [collages] make it into the book?

JEREMY: Because you didn't like them. [Laughs]

LIZ: Ergh, sorry, not sorry.

JEREMY: Which is fine. I mean those early collages were intended to map the space, to explore. It helped me discover source material and helped me talk through themes with you. And [it] sort of evolved into the right space, grow[ing] into that space.

The Boundaries and Pitfalls of Artistic Collaboration

JEREMY: There's maybe something interesting in this [related to] collaboration. You pitched me early on with, "I want to bring you into [my] book projects. I'm writing books. I want you to make art for them or design covers or, you know, illustrate somehow. [To] do things on the visual side to accompany [the writing]. Maybe speak on initiating the collaboration a bit.

LIZ: I think it's pretty natural for life partners who like each other and like each other's work to try to put it together somehow. That doesn't always go well, depending on the couple. One of the ways that Jeremy and I have made this work for us is [by nature of] hav[ing] different mediums. And I think we each have pretty clear boundaries around how we direct each other in our different projects. So it was clear from the beginning [that this book] is primarily my project.

So, Jeremy was joining me in the Knock at the Sky book as a partner, but not as the primary creator, and not by speaking into the art itself. So that was clarifying to be like, okay, I'm kind of the ultimate say. But [even so,] I worked really hard to [express], I want you to have freedom to make these [collages] how you want. And there was a process of kind of feedback on some of the more final collages but ...initially, I [said], I want you to feel free to explore the way you want this [art] to look. Because I knew I didn't want these to be editorial illustrations only, as if I was just... a client. You know, he [Jeremy] works in design, so he's used to working with clients, and demanding clients, by the way.

JEREMY: Sometimes. Yeah.

LIZ: I knew [he would feel] more ownership, and also it would be more meaningful if he could contribute in his [own] way to this project, kind of speak back to the work that I was doing. So, typically,... I think [he would] respond to ideas that I had told him about. Or I would send him a chapter once I felt like it had reached some level of completion.

JEREMY: Very first draft.

LIZ: Yes, very first draft...

JEREMY: You'd give that to me and let that sort of percolate.

LIZ: ...but enough to be readable. So it wasn't fragments, it was a full chapter.

JEREMY: Let's pause on that for one second, and go back to initiating a collaboration. There's something interesting [there]. Collaborations can be fraught. You know, you mentioned, if a couple is both artistic and they like each other, you know?

LIZ: And they liked each other's art. [laughs]

JEREMY: Exactly, exactly. There are some instances where you may not want to embark on a collaboration, like it may put undue stress on the relationship or a friendship.

[I learned this from a previous collaboration that went well, for example.] I had previously collaborated with one of my friends who's a composer, and we had created [a film]--a 16-minute long animation. He had written a composition for a five-person ensemble, and I created a 50-foot long, collage that I then photographed and digitally animated. That [collaboration] started as just a mutual recognition of, "I like your work. I like who you are as a person, I respect your work."

And we had to like set clear boundaries around that to say, from the get-go, we don't want our friendship to be at stake. And you and I, we don't want our marriage to suffer because of this [Liz snort laughs], like our partnership shouldn't get on the rocks...

LIZ: That'd be terrible.

JEREMY: ...because we tried to collaborate on something artistic.

So when you embark on a collaboration, having some respect for each other's work, having some mutuality, having some defined parameters around a project are helpful. You had talked about in this [collaboration], we defined, this is essentially your project. You are the lead. The ideas are yours. I'm going to come along, and I think we mentioned this in the previous episode, but that idea of ekphrastic art. Which is art inspired by other art. And you [were] creating this work inspired by this ancient work of art in the scriptures, and then I would come along [after] ..in the third wave, and create art inspired by your art.

...That was really helpful for me to define that at the get-go. There [was] a little bit of a client/designer/commission[ed] artist ... structure here. ... You know, I don't think [my work] was ever going to change the trajectory of this book. Like, I wasn't going to take over and say, well now Knock at the Sky is 90% art and 10% words. [Laughs]

LIZ: Publisher would have had words with you.

JEREMY: It was sold as a different project, although with art from the get-go.

... So [that's] .. something that we've learned experientially around collaboration with artists and with friends: define those things up front.

But what happens when two married collaborators disagree?

LIZ: That being said, we did have some conflict along the way.

JEREMY: It's inevitable.

LIZ: [The conflict] wasn't super notable. Can you think of some times when we disagreed, or let's say, where you didn't like the direction I was taking something in my writing? (...Because Jeremy does not agree with everything in the book that I wrote, which I find really interesting.) [Jeremy laughs] So, could you tell me a little bit more about that?

JEREMY: Yeah, I'll say first, from the 10,000-foot view, you and I have worked to cultivate a sense of mutuality and autonomy in our relationship, where we each are allowed to show up in our relationship as a full human being with our own opinions and our own perspectives. And that's okay. And that doesn't need to threaten our partnership.

So, that's a 10,000-foot view, and then on the granular [level, related to this book]: ...I held this tension of, I'm creating a work of art, but I'm also doing it for a client... sort of. And that gives me [better] internal boundaries--say, if you don't like a particular image, [or] if you look at a collage and you say, this is distracting to me, [it's less personal].

...at one point we reviewed all of the works together, and they were a few [collages] that felt off to you--like, this one is feeling flat, or I don't get this idea here. We talked it through, and that sort of outside perspective is helpful for me as both critique and partnership. But I don't need to feel offended or whatever. I can push back and say, actually, I really want to fight for this. There's a dialogue.

LIZ: I also really want to know if there were any parts [of the book] that kind of made you cringe and [think], do I want to be associated with this?

JEREMY: I'd say, in the actual tactics of our partnership, I think we did reasonably well.

LIZ: I'll take it.

JEREMY: There were moments. ...It was discouraging that my first pass didn't resonate with you, for example, or [moments where] I feel ack, like maybe I would do this differently if it was just my [project]. But part of that is [learning] to accept an actual collaboration. You accept the studio critique, right? You accept somebody else into the process.

LIZ: Like, there are differences between our voices and between our styles and between how we would pursue things. Because we're individuals. Sure.

JEREMY: But I think you're [wondering about] our differences ideologically.

LIZ: Uh huh.

JEREMY: On that front, you and I dialogue. My influence back on your work has mostly occurred in the form of like lunchtime walks.

LIZ: Yeah, we did do a lot of that.

JEREMY: As a [graphic] designer, I'm privileged to be able to work from home which not everybody gets to do, but it's great for me. I also have chronic back pain, and so Liz has been encouraging me to take lunchtime walks to try to stay active. [Laughs]

LIZ: With me.

JEREMY: So, we'll go on walks--for my mental health, for my physical health. And during those walks, we'll [often] talk about the themes that Liz is thinking about. And I am in a different spiritual place than you are. Sometimes we struggle with that, we're not aligned on things, and other times, it's great [because] it sparks conversation and dialogue. Initially, when you were talking about taking your project.. through Genesis [sequential], I was like, "Eh." [Shrugs, laughs]

LIZ: Yeah, like, "I don't know if I'd read that."

JEREMY: I don't know if I'm into that. I'll say, where you took it in the end? Real thrilled.

LIZ: Aw.

JEREMY: I love like the form and the style and how you wove so many interesting things into [your commentary on Genesis].

Lately, I [have felt] unsure if I want to be associated with faith communities, or to be publicly "out" as Christian. [Laughs] It just comes with so much baggage, and I feel much more comfortable in artistic spaces and amongst other artists, people who are not sure about everything. So many these faith spaces are terribly sure, and ready to fight anyone who's not.

LIZ: That's fair. But that's a super interesting part of collaboration—you must release to the other person. That’s just part of the process.

Quantity over Quality (And A Class Full of Philosophizing Potters)

LIZ: So, despite the fact that I had some early critique of the style that Jeremy had chosen [for this project], he is saying that he knew that I would want a little bit of say, at least in the direction he headed. But I was not involved in the individual works [in-progress].

Typically I would see things afterwards, so I think one of the things too about this season of making is that it is generally pretty independent and siloed [even when you are collaborating].

In my process, I usually need to cocoon myself. I need to protect myself from reading things that would be too similar. I typically just read things related to the project I'm working on. So I'm reading very deeply in very specific theological or scientific or artistic crevices. These strange little disciplines that I have found for myself to study.

Do you experience the period of sitting down to work like that? What does that look like for you?

JEREMY: We're talking about the point of the process where you do the bulk of the work, right? [As an artist,] you set a trajectory and, like we talked about in the last episode, maybe you don't have the idea fully formulated, but you have maybe the core questions.

At the point that I really joined the process here in a tangible way, that was after I saw something rough from you. Like a rough first draft of a chapter. That was really the first contact... [Then I could get into] my process. That allowed me to say, here are the key questions I'm engaging with, just by scanning and skimming what you'd written--digging into some parts, glossing over others. I [was] looking for what's visual here [in this chapter]? What visual metaphors can I draw out?

This is a balance between sitting with and meditating on the themes, and then doing something practical with your hands, like actually making something.

My process will look like making a lot of work. And then curating [from there]. It'll be iterative. It'll be trying things, a lot of different things.

So ... in this stage of creating..., first of all, you have to show up. You have to get to your studio, or your writing desk, or your laundry room where you have a tiny table set up in the corner. That was, you know, my studio situation for a while.

LIZ: That was an actual studio Jeremy had, yes. [Laughs]

JEREMY: I had a flat file in a laundry room, and the flat file was also a desk. And that's where I worked. Wherever your setup is, [you need to] get there with regularity, showing up engaging with your materials and your practice and doing something.

For a long time, what this project looked like for me was gathering source material, cutting out clippings, making little palettes ...of images in the same way that a painter makes a palette of paint. I would say, here's the world that I'm living in for this collage. And I would usually work on three to four [collages] at a time so that I could also see them as a series. I could see, are they saying something back and forth [to] each other? Is there a through line that I can identify between these different topics, these different chapters, these different works of art?

LIZ: That's interesting that you worked on so many [collages] at once. My process was not like that. I had to get through one chapter at a time. And there were so many different elements in the chapter, so I definitely had, let's say, a palette of stories--you know, I'm working on this story, I'm working on this story. But at some point, I needed to just finish the chapter, just [to be done with the thing. And, in fact, the middle of a project is often the hardest for me.

It's kind of like middle doldrums. [Laughs] It just like feels...

JEREMY: A slump?

LIZ: Yes, ...I'm over the part that is exciting and new. Then I'm really into the meat of the project, and that's when self-doubt tends to creep in. You know, book writing is a long process, a long, long process. From the time when I first had the idea to when I signed with the publisher, it was a year and a half? And then when I was working on the book, it was like six months of intensive work. By that point, I'd already gotten about 100 pages in before I signed with a publisher. Then I was having to get into the meat and [saying], can I really do this? And there's there's an element in which you just have to keep pounding out the words.

JEREMY: I love that idea of showing up whether you're feeling it or not. Whether it's like, I have the inspiration, I have this manic energy to go create something. Or...

LIZ: That's kind of the best though.

JEREMY: Or I'm feeling down in the doldrums, just showing up and making stuff [anyway]. You and I have talked about the book Art and Fear--which, amazing resource...

LIZ: Yeah, one of our favorites.

JEREMY: ...for any artist or creative. Go read Art and Fear. But they tell a story in that [book] about a pottery class. The teacher... sets a grading scale for one class and says, you'll be judged on the [perfection] of one pot at the end of the semester. And to another class, the same teacher says, your grade will [be based on] making the most pots you can. So, the one class was sparing in their creation of pots, they were slow, and they were perfectionists...

LIZ: They did a lot of philosophizing about, what's a perfect pot?

JEREMY: Yeah, how do I make the best pot? And then they made very few pots. And their pots were actually worse than the class who just cranked them out, pot after pot after pot. And [the difference came] down to the actual repetition and putting in the work of showing up every day and [making] a lot of it. ...As artists, we can be a little precious with our artwork especially if it overlaps with [our limitations]--"I only have so much time to make art, and so when I show up it needs to be useful and perfect, and I need to make something that's valuable. ...And if you have this faith overlap, it [becomes] ... "God's calling on my life." So [there's] so much extra pressure.

I think there's a lot of wisdom in that: don't try to make something perfect. Try to make a lot, try to make the most you can. And not [necessarily] at the sacrifice of quality, but don't be precious.

LIZ: Well, yeah, just be faithful. Just sit in the chair. Just tap out the words.

JEREMY: Right, just keep showing up, keep making stuff.

Conquering the Inner Critic and Learning from the Biblical Scribes (Who Wrote the Bible Over and Over and Over Again)

LIZ: [At a certain point,] it’s actually more important for me… to set word goals than content goals. Did I write 500 words today? [Then] I did exactly what I was supposed to do. Were they good words? I don't know yet. But I wrote them.

JEREMY: It may be a little different for me [in this particular book project, Knock at the Sky,] because my task was 11 pieces of art, and they're small. And so it was less about like meeting a quantity. Although, I still over-created and made more than I needed to.

I was also still making all of my regular stuff. I'm still in the studio, I'm still practicing [in] my regular art practice, as well as design and other things. But I made a lot for this [book], I found a lot of source material, and then I'm curating to decide [which of] these [many collages] are the final ones.

And ...[then, in my practice, I try to ] give [the art] a little space to breathe. Especially in this case where [the work] is going to be a singular thing, viewed one at a time sequentially through this book. And I wanted them to feel spontaneous and not overworked, but intentional. ...So there was [a stage]... of letting them rest.

So, [I'd make] a series of these collages, then let them sit for a week, then come back and look at them with fresh eyes. [I wanted to see,] which ones are making me, feel something? Which ones are actually doing something? Are they telling a story? Are they relating to the words on the page?

LIZ: Yeah. I personally felt really inspired [learning about]... how the Bible was made. Not philosophically. I mean the materials. How did they make paper? This was way before the printing press, right? So how did [the scribes and authors] make the paper? How did they make the ink? How do they make the pen where they put the ink? And for paper, it was this painstaking process of growing reeds, and drying reads, and making glue, and then drying all the reeds you've woven together. And one of the things that was so inspiring to me was realizing that the writing actually never stopped.

So even after... a draft of the Bible was written, in a culture like that it's not guaranteed that those materials and those texts are going to stick around, right? So there is this constant restoration of the texts that scribes participated in. They're making all the [materials for writing], and they're also writing and rewriting the same text over and over and over again. That's the reason we have any of the Bible that we have today is because people by hand made papers, made ink, made pens, wrote and rewrote the same words over and over and over. ...It actually gave me a lot of more respect for the fact that I have those words now, that ancient peoples across centuries viewed these same words as equally important in their own ways for their own reasons. And they wrote, and they wrote, and they rewrote, and they rewrote.

And for me that was heartening. Here I am tapping at my computer, but I'm not the first writer to have to deal with this [repetitive, painstaking process].

JEREMY: Yeah, but did the scribes have to deal with Dropbox? I mean, crashing, computer drives, the screaming into the void over your lost files...

LIZ: That actually is a great question, and the answer is no.

But you know what, I did have a moment. I [had] saved doing the end notes till the end [of the writing process], and there are, like, 300 end notes. It was like such a stupid decision, never doing that again, especially because Dropbox screwed me over.

JEREMY: This book is well researched, I mean, 300 end notes. Check out the bibliography on this sucker.

LIZ: Check out the bibliography, man. That's all I read.

JEREMY: I like a big bibliography. [Laughs]

But I love what you're saying about the scribes and the practice of showing up everyday for this discipline, and there's a lot of artistry that went into these hand-written and drawn manuscripts, back in the day--obviously, the parallels to illuminated manuscripts and making art that will accompany a book like this. There's a lot of overlap there, right? Maybe you would apprentice in a community of other scribes [to learn the craft,] but the task itself is solitary and methodical, maybe not a whole lot of rewards along the way or acclaim. You just show up and you write. Then later on, you hope that that work was fruitful, and there was some connection to other humans, that occurred because of it.

LIZ: But in the action of just showing up, there really is not [an] outcome orientation. I mean, ...you hope it will outlast you, you hope it will help the community, but... there's not much that you can control beyond just sitting down and writing today.

And so, that was the most important thing [to remember as I wrote this book], because I did feel pressure. Why am I writing about Genesis? What do I have to say about this ancient masterwork? You know, who wants to hear from me? [But] at some point, you just have to say, you know what, I'm going to put all those thoughts to the side. I'm just going to put them away, and I'm just going to sit in the chair and keep writing.

JEREMY: ...There's often an inner critic, you know, the voice of self-doubt that will say, nobody cares. Why are you making this? Who cares? And yet, many of our most beloved artists that we remember, [our] ...heroes of craftsmanship, were unknown in their time. Van Gogh, Emily Dickinson, very obscure in their own times, but obviously convinced [by an]... internal validation [that said,] it is worth it to show up. It's worth it to keep making art. Who cares about your credentials? Van Gogh was a failed preacher, failed everything, starving, mental health issues...

LIZ: That poor, troubled man.

JEREMY: But absolutely convinced of the need to paint, and [he] showed up and painted. And it's like... I mean, what a terrible life...

LIZ: ...and he's who were basing our lives on, everybody! New hero.

JEREMY: Cool... Ready to go to work.

But ...there's some measure of that... to adopt for yourself. Say [to yourself], making art is inherently worth it. It is a good use of time, and it doesn't have to utilitarian--like, art is worth it if you have more than a thousand followers on Instagram, art is worth it if can make twenty thousand dollars a year doing it, or whatever. It doesn't have to be that.

Making art means that you are living a life that is well lived, an inhabited life.

LIZ: It's a contemplative practice.

JEREMY: That's worth pursuing.

LIZ: That's worth it.

--

We hope you'll join us for some trauma bonding in episode 3, where we'll be discussing revision--that is, the moment when you share the work and realize to your horror, that it isn't perfect. And you need to change everything about it... yesterday. We'll see you then.

About Jeremy and Liz

About the Author

Liz Charlotte Grant is an award-winning essayist whose work has been published in The Revealer, Sojourners, Brevity, The Christian Century, Christianity Today, Hippocampus, Religion News Service, US Catholic, National Catholic Review, The Huffington Post, and elsewhere. Her essays have twice won a Jacques Maritain Nonfiction Prize. She also writes The Empathy List, a popular substack that has been recognized by the Webby Awards (‘22, ‘23) and the Associated Church Press Awards (‘23). Knock at the Sky is her first book.

About the Artist

Jeremy Grant is a multi-disciplinary artist whose work is rooted in contrasting modes of natural and mystical experience through a practice that bridges association and obfuscation. He has exhibited work regionally in Colorado since 2008. His 2019 film “Remnants” was exhibited at the Supernova Film Fest, and the Denver Film Festival. He holds degrees in Graphic Design and Illustration (John Brown University, 2007).

[American, b.1985, Monterey Park, CA, USA, based in Denver, CO, USA.]

Me: Yes. So true. This is hard work but it is good work, now let's do it.

Also me: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cSUcyz5hUHc