Curious Reads: Revisiting The "D" Word (Deconstruction)

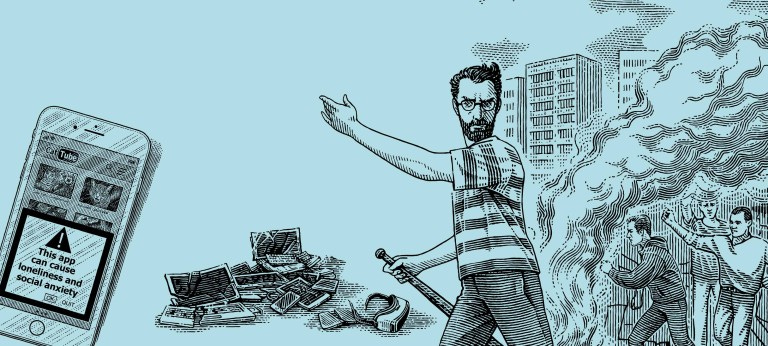

Jacques Derrida would take issue with the way evangelicals use the word "deconstruction," says philosopher Dr. Bruce Ellis Benson. (Art by Jeremy Grant)

Hello friend, Liz here.

#1 Today’s top of the fold story is a conversation that redefines the term “deconstruction.”

That is, while former, ex-, and current evangelicals have embraced the term as a means of tearing down and excising harmful ideologies and religious practices from their Christian faiths (especially within the white American evangelical church), the term’s creator had a different take on the word’s meaning.

Turns out, we’ve been using the word “deconstruction” wrong.

Listen to the New Evangelicals podcast #181 with Dr. Bruce Ellis Benson “The Truth About Deconstruction is…”

Here are the highlights:

The philosophical forerunner of Derrida and his idea of “deconstruction” is Edmund Husserl, who said:

We must start philosophizing from our experiences, “the real stuff—the things we experience as we experience them, and the attempt is to make sense of that experience.” Because “many things we experience on a daily basis, we never stop to think about.”

In that way, Husserl’s approach does not differ much from St. Ignatius his religious practice of examen, which takes daily inventory of the emotions and experiences of the day alongside God so as to make meaning of our lives.

Husserl is seeking unviersal meaning from particular experiences.

Start on the ground, then view from the clouds.

Husserl’s ideas of building and unbuilding are the base of the theory of “deconstruction“ later. Husserl developed the concept of “abbau,” meaning to “un-build” in German (“bauen” means to build; “abbau,” to unbuild). Husserl’s idea is to “unbuild” by taking apart ideas by their components so as to understand it.

Then Martin Heidegger, a student of Husserl, builds on that with his term “destruktion” (“destruction”), by which he meant, we need to redo philosophy from the past and re-approach their conclusions with contemporary questions.

Heidegger decided the conclusions of the past were inadequate. They both “concealed and revealed” the original sources. So, current philosophers needed to “‘take apart’ former understandings,” to undergo a reinterpretative process that would import meaning of past wisdom into our current setting. That repetition, undergone from our unique place in history, would reveal whatever past thinkers may have missed due to being, themselves, in a different setting than our own.

Jacques Derrida is the father of the term “deconstruction” in philosophy.

Derrida developed his term in conversation with Husserl and Heidegger. However, he tried to soften their versions, as he found Heidegger’s “destruktion” to be too negative. So was born the idea of “deconstruction.”

When Derrida looked up the word in the dictionary, it meant, “To take things apart in order to rebuild, to disassemble, as in disassembling a car to ship it in parts.”

Ironically, evangelical pastors often assume that because the term originates with a postmodern philosopher in the 1970s, that implies that the “deconstruction” is a devaluing, a demolishing, an undoing. They think deconstruction is nihilism by another name. They would summarize “deconstruction” as “words have no meaning and nothing matters, and it’s all subjective… so let’s just tear apart everything… because everything is relative.”

In other words, nothing means anything, so blow it all up.

But this is not what Derrida meant at all.

What is “deconstruction” according to Derrida?

“Deconstruction” was never intended to be a “method, it’s not analysis, it happens apart from anyone wanting to deconstruct or not,” says Derrida explicitly within his writings.

Dr. Benson elaborates:

“Let me give you an example that will cause your head to spin around. Here’s my favorite example of deconstruction: bible commentaries.

Think about, what is a bible commentary? You’re looking at a particular passage…, say, on the Gospel of Matthew, somebody’s looking at chapter five to see how that relates to chapter four… to see how that relates to the rest of the book, etc., etc. Deconstruction in this case is, ‘Here’s what Matthew says. But it seems that what Matthew’s getting at is...blah blah blah blah blah. And that ‘it seems like…” question, that’s deconstruction.

Another example: if you were sitting in a classroom and a professor just said something and you missed it, and you said to somebody sitting next to you, ‘What did he say?’ Now, if the person just simply reproduced—he said, ‘blah blah blah blah blah,’ that’s not really deconstruction. But if he says, ‘Oh, he was just talking about the homework, you don’t need to worry about it,” that’s deconstruction. Because it’s an interpretation of the text and commenting on what that text does and its function.”

Notably, deconstruction implies an inherent meaning.

Meaning comes from the authorial intent of a text—a person communicating something that they want to be understood—and also its reception. (“Text” does not only refer to writing, but to “experience” as well.) The reception of that communication is where interpretation—and deconstruction—happens.

Another example of deconstruction: the story of the Good Samaritan.

As Christians, we read the parable of Luke 10 and we immediately turn the story on ourselves, asking ourselves the same question as the pharisee asked Jesus—who is my neighbor?—and applying Jesus’s answer. Preachers may call this application. What does the story of the Good Samaritan mean for me right now? Who is my neighbor?

Deconstruction is asking, how do I make meaning of this text within my own context?

We reinterpret and so “deconstruct,” examining the component parts—the spirit of the text—so as to apply meaning to our lives today.

In Truth and Method by Hans-Georg Gadamer, for example, asks, how is it possible for me, living in the twenty-first century, to read something that was written two thousand years ago in another language and discover meaning for today? How do we interpret the Bible or any other classical text?

Gadamer suggests that we make meaning through what he calls, “the fusion of horizons.”

"Your horizon can fuse with the horizon of Plato or Paul…and that’s what happens when we understand one another. Now, we do not have perfect understanding because we cannot get into each others’ minds.”

Of course, we cannot share each others’ thoughts. But we receive clues, we interpret speech and body language, and the communication we receive is effective enough to help us share ideas with each other. However, the fact that we cannot understand each other exactly is the reason “deconstruction” is necessary.

There is always an interpretative aspect to language.

In the case of the Bible, says host Tim Whitaker, “That’s why we have hundreds of denominations and church schisms because we’re trying to understand what these things mean. We’re learning from dead people! So we have to make meaning without their help in defining [themselves].”

Whenever we’re interpreting, we’re participating in the act of “deconstruction.” All interpretation is deconstruction.

A popular definition of deconstruction is “un-building.” As in Tim’s example: “I thought I was building a complicated piece of IKEA furniture and three-quarters of the way through, I realized I’ve built it backward. Now I have look at all these pieces again and reassemble them in a different way.” It’s a renegotiation of faith.

But "faith deconstruction” in popular parlance spans deconversion and rebuilding both, with an emphasis on the negative. It’s become a catch-all phrase.

Derrida would likely take issue with the negative use, assuming deconstruction to be closer to the more neutral definitions of “observation and interpretation,” rather than the negative connotations of “demolition and destruction.”

“Blow it all up” and deconstruction are not synonyms.

In fact, Derrida got into trouble in his native France in the 1970s because, when public schools started eliminating classic books from the curriculum, Derrida objected. He thought, yes, reexamine, reinterpret, but do not excise completely. Don’t throw out what centuries of readers have found valuable without giving it a chance to speak to you, too.

What would Derrida say to those who have “deconstructed” their faith so dramatically that they no longer believe?

I think Derrida would say, “Oh, you’ve deconstructed and you’ve left; you probably haven’t deconstructed enough.” Theology has to be done for every generation. Theology is constantly in motion.

And because meaning exists objectively, perhaps our context offers new interpretations on classic stories and belief systems. As in, there’s always more reexamination to do—whether that results in an individual remaining Christian or not is not the point. The depth of interpretation is the point, according to Derrida.

The fact is, it’s impossible to entirely leave Christianity in the West because the tenets of Christianity have marked our society. For example, Western society maintains Christian morality as the baseline, rather than, say, Aristotelian ethics which considers women to be defective men and other men as natural slaves and so naturally inferior (“they were meant to be slaves because they’re lesser men”). Jesus’s idea, on the other hand, is that everyone is loved by God. And that’s informed our justice system.

Tim explains:

“Does Christianity have some serious issues? Yes. But whether we like it or not, a lot of the principles we get about freedom and equality… tie back down to some form of Christian ethics at the root.”

Further, Jesus himself engaged in a form of deconstruction, disentangling and renegotiating his faith.

He says to the Pharisees, “You say whoever gives to God what he would normally give to mother and father owes nothing now to mother and father because it has been given to God.” Then he says, “You hypocrites,” and he quotes from Isaiah, interpreting that ancient passage for his time. That is as close to deconstruction in a classical Derrida sense as you could get.

If we think that Jesus deconstructed everything that needed deconstructing, that in the 2,000 years since then we have nothing to deconstruct (in Derrida’s sense), then we’ve missed the point of Jesus’s teaching. One can be true to the spirit of Jesus—what he’s trying to say and what he’s trying to do—by criticizing people who actually say things that go against what Jesus says.

Whatever does not square with Jesus should be recalibrated.

What does the term “deconstruction” mean to you? How would you reinterpret the term for yourself, for your peers, for the Christian church in this moment? Does it feel relevant or flat? Why?

Derrida spent his entire career reading ancient texts and he once gave a talk at a New York Law School in the 1970s called “Force of Law.”

Derrida said, “Deconstruction always has been about promoting justice. And justice is not deconstructable. All specific instances of justice can be deconstructed, but the concept, the ideal of justice is not deconstructable.”

This is wild to me. The father of “deconstruction” says here that truth is untouchable. This postmodern philosopher, so maligned and misunderstood, believed that justice could not be deconstructed. Because deconstruction’s final goal is justice.

What could be more Christian?

Deconstruction is not led by fear, but by truth and a desire for justice. What if we reframed our doubts, wonderings, and examinations as a search for indestructible justice?

“The word of God endures forever.”

“Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever.”

“And God is the One who keeps us from falling.”

Friend, do not fear what dogs you. Open yourself to the work of reinterpretation, rexamination, and application. “Deconstruction” is not a dirty word, injustice is.

Thanks for reading! Warmly, Liz Charlotte Grant

More Curious Reads

#2 Understanding the war between Israel and Gaza is not simple. And the media and political actors do not always offer context or explanations that can help us laypeople to understand. So, I found this glossary helpful for those of us without international humanitarian law degrees. ;-)—Vox

[By the way, I have no idea how to speak to the complexity of this Holy Land war. Like you, I am listening and learning and praying instead, depending on the wisdom of experts and those involved to clarify what it means rather than offering an uninformed opinion you don’t need anyway. Listen, learn, pray. This is a reasonable and wise response. You don’t need an opinion, just open ears. Lord, have mercy.]

the Empathy List is a one-woman show supported by generous readers like yourself. If you like this edition, subscribe! And if you have the budget to spare, buy me a coffee once a month to say thanks & to gain commenting access. ;-)

#3 Everyone is a luddite now. A story about the anti-tech pranksters of Silicon Valley. —Wired Magazine

“An enterprising activist had observed (or perhaps gotten an insider tip) that placing an object on the hood of a self-driving car blocks the sensors it uses to see the road. The car freezes. Many objects would do, but [traffic] cones were handy, undamaging, and happened to transform Cruise’s robotaxis into four-wheeled unicorns…For weeks this summer, ahead of a state regulator’s decision to expand their reign, the city’s AV fleet was stricken by merry nocturnal raids.”

#4 Britney has a tell-all memoir out. And it’s as dark as you’d expect.—the Guardian

#5 Give a hearty yeehaw for these newest limited edition crocs and treat yourself to a few of the goofiest reviews. —The Denver Post

Just for Fun…

A 1978 Star Wars spoof I never knew existed. (The entire thing is framed as a preview, BTW. Took me a while to catch on… haha.)